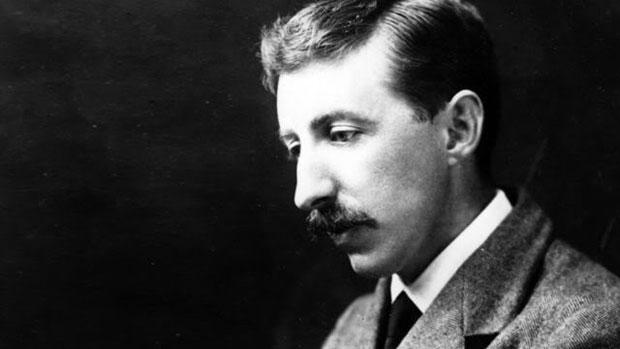

E.M. Forster, when discussing novels, observed that the narration of “the king died and the queen also died” was a fact, but “the king died and the queen died of sadness” was a story (1). A story establishes connections between facts. To combine the facts and change them into stories is a reflection of literature’s narrative power. Historical narration is the same. It not only records facts, but also “produces” the connection between them, resulting in a tale that imparts political, social, and religious significance.

Religious texts are not historical in the modern sense. But they have always made use of history to articulate their authors’ insights. In Classical Chinese and Chinese Buddhist literature, the use of allusion has come in different forms, but its function has always been to appeal to that period which the Chinese treasure so deeply: the ancient past, an era that grows ever more distant with each generation and is hence idealized further and further.

To understand this essayist technique, we should situate it in the broader context of Chinese writing. Classical historians like Sima Qian (145 or 135 BC – 86 BC) were determined to make history books useful. They argued that historians had a duty beyond merely recording things, and that history examined the relations between Heaven and humanity. History meant being conversant with the teachings of their forebears and contemporaries, and for writers to leave behind their own ideas. But a book that only recounted facts wasn’t going to attract a readership. A story needed to be told. A common audience found history useful because it could teach and reassure them of rewards for the just, punishment of the wicked, and protection under the Emperor or religion. To realize this agenda, writers as diverse as imperial archivists and Buddhist preceptors realized they needed writers with flair and imagination, so that historical facts could become stories and attract readers. Only those with literary persuasion could combine their talent for words and expressions with history.

Confucius (Kong Zi) was the first in Chinese history to mention the relationship between history and literature: “only when literary grace is better than the facts can it become history; otherwise there will be facts, which will only be contents in chatter” (2). Confucius saw literary grace and sacred Nature as one. Nature could be found in the ornamentation and uprightness of words, but also in the form and content of the words. In both cases, history is proved to literally possess a literary nature, or a natural literature, with perfect words or pleasant forms enhancing the content. Nature effortlessly and modestly conveys facts, while literature combines man-made techniques with a natural inspiration. Affairs and events are the domain of nature, while literature can tell better stories. No wonder, then, that literature and nature could even seem the same.

The Southern Dynasty (420 – 589 AD) was a dynamic era for Chinese and Buddhist literature. In addition to the theory of rhythm in poems, allusions arose as a distinctly new literary phenomenon. Zhong Rong noted that there was a great need in “usage” in literary creation. These so-called “usages” are derived namely from allusions, and the meaning of “uses” and li shi are the same – literary allusions. The utilization of literary references includes two aspects: coining language and using allusions. Creating language is to select words and phrases, and using allusions is to refer to past events. It is through the use of the old sayings and past events that feelings and views can be communicated.

In the “Chapter of Self-Immolation” of Hui Jiao’s The Biographies of Eminent Monks, the author uses historical facts, including the characters’ birthplaces and family backgrounds for his own purposes. In addition to presenting relationships between influential people and the characters, the author also uses unusual natural phenomena (that appeared during or after the characters’ deaths) as proof of their talents and merits. For example, Seng Qun, Fa Jin and Hui Yi were praised and admired by Governor Tao Kui, Meng Xun and Emperor Xiao Wu respectively, and Seng Fu was given financial aid by General Yang Yi and collaborated with the great scholar Xi Zaoci. We can admire the hard-practice of Fa Jin’s disciple Seng Zun, the virtues of Hui Shao’s master Seng Yao, and Fa Cun burning himself for the Buddha.

Certain locales appear in the biographies to craft a sense of history, and possess the Buddhist piety of the author. For instance, Huo Mountain, where Seng Qun dwelled, was also the place where immortals wandered; thus, this mountain (and Seng Qun himself) was implied to be transcendent. Tan Cheng fed himself to a hungry tiger in Peng Cheng, a place of Buddhist diffusion since the eastern Han Dynasty that alluded to his great spirit and bodhisattva-like bravery. Fa Yu burned himself to death in Pu Ban, the capital of ancient times, and the grief and sorrow that ensued implied that the practice of Fa Yu was accepted by orthodox China. Hui Yi pleaded with the emperor to protect Buddhism, signifying the importance of politics for the development of Buddhism. Seng Qing burned for the Buddha, protected and spread Buddhism in Ba Shu, a region where rival religions were popular.

The writing techniques of allusions represent a philosophy of observing many eons of Bodhisattva practice. As Reiko Ohnuma points out: “the bodhisattva himself usually speaks from the perspective of the ethos of the Ja?taka – seeing himself as an ordinary body struggling on the long moral-path that ultimately leads to Buddha-hood in the far-distant future and often emphasizing this body’s worthlessness” (3).

For a Buddhist, history reflected in the senses cannot tell the full story (quite literally). People remember according to their personal hopes and biases. However, if the memories and references they have are integrated with history and narrative, the stories they hold can at least shape for them an open-ended, multifaceted reality.

(1) E. M. Forster, the Aspects of the Novel (New Delhi: Atlantic, 2001), 75.

(2) Kong Zi. Lun Yu. http://guji.artx.cn/article/710.html. Passage translated by me.(3) Reiko Ohnuma, Heads, Eyes, Flesh, and Blood: Giving Away the Body in Indian Buddhist Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007): 270.