I recently returned to Hong Kong from presenting two papers in the southern hemisphere. The first was at the 2019 Australasian Society for Continental Philosophy Conference at the University of Melbourne from 4–6 December. The second paper I presented was to the New Zealand Association of Philosophers Annual Conference at the University of Auckland from 8–11 December.

Immediately prior to this, my wife and I traveled from Hong Kong to Sydney on 30 November to visit friends. I eagerly anticipated giving the presentations and taking part in the busy conference programs with the other speakers and attendees, but my extended trip also offered me an opportunity to encounter and write about some of the unique cultural aspects of Australia and the state of Buddhism in the country.

The history of Australian Buddhism goes back in 1848, with the arrival of Chinese immigrants to the Victoria goldfields. This was followed by the arrival of Sri Lankans in 1870s to Queensland and the Torres Strait Islands. Toward the end of the 19th century, Buddhism began to grow in conjunction with the immigrant population. More recently, according to 2016 census data, 2.4 per cent of Australians were affiliated with Buddhism, making it the fastest-growing religion in the country. Buddhism is now being taught in some primary schools during religious scripture classes. I was astonished when my friend, Shyamonta Barua, told me that he was enaged as a schoolteacher for the express purpose of teaching Buddhism.

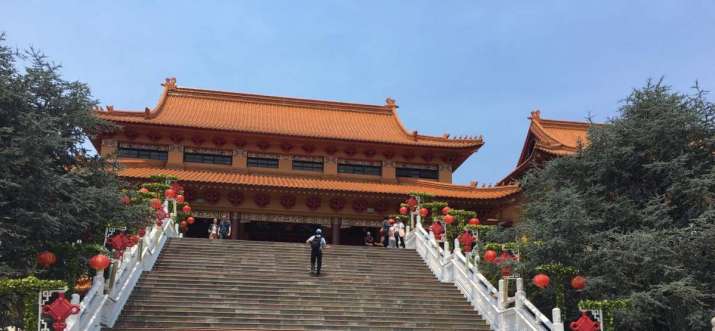

Nan Tien Temple, Berkeley

After our arrival in Sydney (which is presently choking under a cloud of smoke from the massive wildfires that have become a source of great national distress), we were invited to join a tour to the Nan Tien Buddhist temple with a group of people who were born in Bangladesh. Built in 1995, Nan Tien is a branch temple of the Taiwan-based Fo Guang Shan Buddhist organization. Nan Tien Temple is located in Berkeley, on the southern outskirts of the Australian city of Wollongong, some 80 kilometres south of Sydney. The temple overlooks Mount Kembla and Mount Keira, an auspicious vista as they are “sister” mountains and Mount Kembla is said to resemble a recumbent lion.

Nan Tien’s architecture is distinctly Chinese, but built using modern methods and technology. Entering the temple complex, we encountered a pleasant garden bisected by a path leading from the main gate to the main temple. The temple itself contains the two shrine halls, the Great Mercy Shrine and the Great Hero Hall, within which multiple monumental Buddha and bodhisattva statues are housed. We stopped at a dedication altar before these icons to pay reverence to the Buddha. Before proceeding into the main hall, we encountered the thousand-armed Avalokiteshvara in the front hall. In this hall, there are also the five cosmic Buddhas: Amogasiddhi, Ratnasambhava, Vairocana, Amitabha, and Akshobhya in different meditative postures. Both halls house small statues of the Buddha on the walls.

There is a vegetarian restaurant inside the temple complex serving a delicious family lunch. After eating there, we took our time to visit other remarkable areas within the complex, including a museum of art and culture. We then headed to an eight-level pagoda also built in a distinctly Chinese style. The shrine inside is dedicated to the bodhisattva Ksitigarbha, who vowed to help all beings to escape the hell realms and reach enlightenment. There is also a wishing bell, where we took the opportunity to make our own wishes.

Our last stop was the Nan Tien Institute, a private government-accredited higher education institution focusing on applied Buddhist studies, health and wellbeing, humanistic Buddhism, mental health, cross-institutional studies, and mindfulness for schools. All of these academic programs incorporate contemplative education, allowing students to contribute to the advancement of knowledge, culture, and ethical understanding, both for the benefit of themselves and for society as a whole.

While we walked around the complex, I recalled a visit to a similar center belonging to the Fo Guang Shan organization: Hsi Lai Temple and the University of the West in Los Angeles County, California, which I visited in 2016. Both temples and academic institutes are run by Fo Guang Shan and focus mainly on the humanities and social sciences.

As we left, I remarked to my friends how well-maintained Nan Tien Temple and the institute were. I was also pleasantly surprised by the large number of visitors. As I gazed back at Nan Tien Temple, I was moved by the fact that this was the first Buddist temple I had ever visited in Australia. I felt such an overwhelming sense of peace during the visit and will remember every moment.

Australian Buddhist Vihara, Katoomba, and Wat Pa Buddharangsee, Leumeah

On our second day in New South Wales, my friend Sapu Barua was kind enough to take us to the Blue Mountains, a rugged region west of Sydney known for its breaktaking scenery. This idyllic location was also the venue for the recent 16th Sakyadhita conference in July. Before exploring the Blue Mountains, we visited a Sri Lankan temple known as the Australian Buddhist Vihara at Katoomba. Established in 1972, the temple operates as a meditation center where people can experience the tranquility achieved through meditation for themselves.

On our way back to Sydney from the Blue Mountains, we also dropped by Wat Pa Buddharangsee, a Thai forest monastery in Leumeah. Founded by the Mahamakut Ragawithayalai Foundation, the monastery offers meditation classes, Dhamma talks, and discussions as part of its religious services. It is also home to a library containing volumes of Buddhist texts in English and Asian languages, including books on Buddhism and related subjects.

Bangladesh Australia Buddhist Society, Minto

On the last day of our trip, we were able to meet the Bangladeshi community at a temple run by the Bangladesh Australia Buddhist Society at Minto. Founded in 2005, the temple’s abbot is Venerable Adiccha, a Bangladesh-born Australian. This community of Bengali Buddhists hail from Chittagong and count among their clansmen the common Buddhist surnames of Barua and Chaudhary. I was immensely moved by their significant attempts to protect, nurture, and grow the religious, intellectual, and cultural traditions among Bengali Buddhists living in this part of Australia.

As I left Sydney for Melbourne, I remarked to my friends that the Buddhist temples and communities were already my favourite destinations. They provided me with the most memorable and enjoyable experiences of my trip. As a seeker of Buddhism, I promised myself that the next time I have an opportunity to visit Australia, I would spend more time with Buddhist communities to learn of the Buddhist culture of harmony and inclusiveness there.