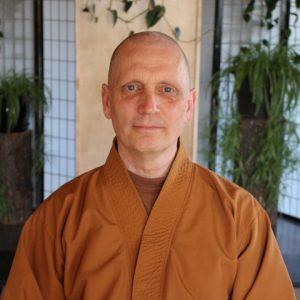

Ajahn Sona, abbot of Birken Forest Monastery in British Columbia, Canada, offers Buddhist wisdom about how we work with some of the identities and priorities that can take up so much space and energy in our lives. In particular, he suggests, anger and hostility can play an outsized role in our mind in this age of polarized politics and high-speed communication. In his book Bloom: Buddhist Reflections on Serenity and Love (Sumeru Books, 2020) he reminds us: “you don’t have to have an opinion about everything.”

When I ask you to tell me your story, who you are, you will only pick out one tenth of one per cent of your life, and you might arrange that as the representation of who you are, what you’ve done, and so forth. But it’s only a tiny percentage of the thousands, the billions of thoughts that you’ve had, of all the motions of the body. When people describe their life, they choose things like, “I owned a motorcycle store. I’m a businessman.” That’s just one of the things you do. Others might describe themselves as sleepers.” I’m a sleeper. I sleep eight hours a day.” There was a French artist who was asked, “What do you do?” He said, “I’m a breather. I do a lot of breathing. Mostly breathing.”

It’s true. Of all the activities that we do, we could certainly say we mostly breathe. How we choose to define ourselves in the past is just arbitrary; it’s a story emphasizing one thing, not another. Why this and not that? Maybe you repeated a whole series of things, but maybe one moment was spectacular. Maybe it was spectacularly bad or it could be spectacularly good. Which one are you going to choose? Moments, or repetitions, or unconsciousness, or dullness? It’s just arbitrary. There’s nothing to grasp. The past is incomprehensible. The future’s unpredictable. This is the way it is. The Buddha is saying that this complex human mind that can understand the ideas of future and past can also have some unfortunate effects if not handled well. We’re not given the proper instruction.

Neither at the time of the Buddha, nor certainly to this day, is it ever fully explained to us how to manage being alive as a human. We’re trained to do jobs; we’re scheduled for this and that. We have arbitrary information. We read all kinds of books about people’s lives. You read a book about somebody you really know and you think, “Well, maybe it went that way.” Or you read an article where someone writes something about you. It’s very fascinating, but that’s not the way it was. The Buddha is summarizing it for you because this is the most important information you’re going to have in your life: how to manage this thing called “time” which is a product of your mind. Your life is a product of your mind. When we talk about your life we’re actually talking about the thought processes. Your life is nothing but the thought processes. We can manipulate them; we can do incredible things with those thought processes with very simple technology. The Buddha gives you the technologies. Try this: try watching your breath. Notice the breathing; notice the lovely, light airy quality of this. Ride away into that airy quality. Allow the sense of the body to drift away.

Do you start to see that your body is really a product of the mind? You see that as you change your mind, your whole experience of your body changes. As you change your mind, your whole experience of your relationships to others changes. As you change your mind, as you do these techniques, how you regard your past changes. The future changes. You start to understand that from a certain point of view, you can transform the very world you live in: the very structure of reality depends on the careful use of the mind. The Buddha is saying, “Don’t chase around out there. You’re the source. It’s in your mind. Turn towards the mind.” All you need is just a fairly quiet environment and a handful of techniques, spiritual exercises to take along with you.

Then he briefly explains the impediments to the good life. What is it that ruins our life? What is it that mildly distresses us? What can lead to profound problems? Only these: aversion, and desire, and confusion. What can you do about that? First, just listen to that idea and realize that’s the source of it. Don’t ignore that. That’s the arising of wisdom. Secondly, to find out what you can do about these things, he says you can take just a handful, just a few teachings. The most problematic emotion, the one that hurts the most is hostility, anger, aversion in all of its forms. But the Buddha, with a very kindly smile, says, “Don’t you worry. It’s the easiest one to get rid of.” Aversion is easy to get rid of mostly because it feels so bad. You’re all ears when it comes to freeing yourself of bad feelings, unpleasant experiences. First of all, you may not realize that you have an option. You don’t have to actually critique everything. You don’t have to have an opinion about everything. Everything you see, everything you hear, everything you smell and taste and touch, everything you think. It’s very common for people to keep asking themselves, “What’s wrong with that? Is that good or is that bad?” That habitual process of looking for the fault is where your suffering lies; so realize that you don’t have to have an opinion about these things. Let sights be sights, let sounds be sounds, smells, tastes, touches. Let the flow of thought just be that. Don’t invest in it. Just allow that world to be and realize you’re off the hook. You don’t have to have an opinion about everything. You don’t have to comment on everything. It’s just as it is. It’s way too much work to have an opinion about everything.

That’s the withdrawal from the source of hostility: the unwise focus on the fault. The unwise focus on the fault of you, of your life, of your future, of the people around you, of societies, of political systems, of thought systems, of the weather, of everything. The Buddha just says, “Don’t go there.” Just bring the mind back, say, “Stop that.” See if you can just walk through the day without your mind fixing on the fault of a sight, of a sound, of a smell, of a taste, of a touch. Then you have a lot more time, and you find yourself a lot less stressed, with an incredible sense of freedom. You’ll feel, “I’m off the hook. Could it really be possible I’m allowed to walk through life like this? Is it true I really don’t have to wear ruts in my cortex anymore? Am I allowed to do this?”

Yes, you are, and then you’ve set yourself up for something really beautiful. By the way, you might be asking, “Am I allowed to have a beautiful experience? Shouldn’t I have to pay for it? Maybe there’s only a few people allowed to have this, but am I? Is an ordinary person without any qualifications allowed to have a beautiful experience, without winning the Nobel Prize, or being first in my class, or making a lot of money? Am I allowed to?” The Buddha says, “Yeah, you gotta get past that one.” Don’t even think about whether you should or shouldn’t, whether you’re deserving of it or not. You’re not in any position to have an opinion on it. Just find out.

Bloom: Buddhist Reflections on Serenity and Love excerpt from Section 2, chapter 9 “Opening the Eye.” Reprinted with permission from Sumeru Books.

See more

Bloom: Buddhist Reflections on Serenity and Love (Sumeru Books)

About the Monastery (Birken Forest Buddhist Monastery)

Venerable Ajahn Sona: “My 40 years of Buddhism in the West” (The Ho Center for Buddhist Studies at Stanford University)