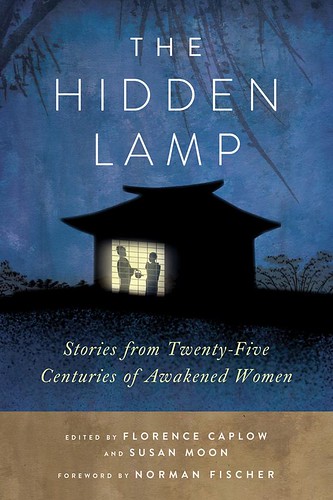

Where can you find a story of an old woman hitting a monk in the face, beating teahouse guests with a fire poker, or expressing her kinship with “mountains, rivers, and the whole earth”? In The Hidden Lamp: Stories from Twenty-Five Centuries of Awakened Women, editors Zenshin Florence Caplow and Reigetsu Susan Moon have compiled 100 women-centered Buddhist koans. Zen Buddhists have often used koans as a tool for Buddhist practice, but The Hidden Lamp (Wisdom Publications 2013) has an additional purpose since it brings Buddhist women to the fore as both characters in, and teachers of the koans.

According to the preface, the book is intended to act as a “foil” to traditional koan collections. By both complementing and challenging koans of the past, The Hidden Lamp seeks to expand the koan canon, making a wealth of stories by and about women accessible to the public. The editors draw from classical Chinese collections such as the Blue Cliff Record and the Book of Serenity, which contain many well-known Zen koans. In addition, Caplow and Moon delve into the sutras for stories of Mahapajapati (the Buddha’s aunt), the Tibetan Tara tales, Dogen’s writings in medieval Japan, and anecdotes of teachers who lived during the last hundred years. The modern koan of Dipa Ma, a 20th-century teacher from India, for instance, is especially affecting. It describes her reaching across an airplane aisle to comfort a woman during inflight turbulence: “The daughters of the Buddha are fearless,” she whispers to the frightened passenger.

Evoking a communal sense of the “daughters of the Buddha” seems to encompass much of the book’s central project. Caplow and Moon are reaching back across the centuries, narrating the stories of women who have practiced Buddhism either formally or informally, throughout history. Even the book’s subtitle, Stories from Twenty-Five Centuries of Awakened Women, asserts a long lineage of female practice.

This assertion, however, is separate from discussions over ordination lineages. Other than a few specific passages, the book largely stays away from the more political arguments of whether or not women can fully ordain as nuns. Instead, it seeks to show that women have always been Buddhists of great wisdom, ferocity, and insight. Whether they are old women hoeing fields, young girls throwing up their skirts at monks, or serving women breaking their baskets in the moonlight, the characters of these koans are fearless and perceptive. The female lineage here is one of conventional and unconventional teachers, strewn across nations, time periods, and schools: all of them Dharma ancestors, all of them daughters of the Buddha.

Each koan is followed by a short reflection written by modern teachers. They represent a variety of schools, although Zen is predominant. Despite their diversity, the teachers have a communal sense of descent from the characters in the koans.

Wendy Egyoku Nakao, reflecting on the story of Ryonen Genso—a beautiful young woman who scarred herself so as to enter a monastery—writes, “Ryonen’s horrific action expresses the depth of her commitment; she enters an endless life-giving stream of women courageously claiming our rightful inheritance as Buddha’s.” By using the word “our,” Nakao connects this 17th-century story to the modern reader, who flow together in an “endless life-giving” course. Similarly, Myoan Grace Schireson connects the reader to the 9th-century nun Miaoxin, whose insightful words awakened 17 traveling monks, by stating, “We are all Miaoxin.”

The koans themselves are delightful, but the reflections that follow them are the strength of the volume. They are not explanations, but the thoughts of the teachers that meander across the pages, providing context, unexpected connections, and their own experiences. Byakuren Judith Ragir writes how a koan of Yasodhara, the Buddha’s wife, helped her connect with the dual reality of being both a mother and an ordained Zen teacher. “Women simply can’t afford to abandon the manifested world while we are raising our children,” she writes. “After 40 years of practice, I’m still practicing home-leaving within the boundaries of a home, just as Yasodhara did.” These personal touches ground the stories, translating them into relatable experiences.

Koans don’t have to be “inexplicable paradoxes or riddles,” the editors write in their introduction. The personal reflections, which range from the academic and abstract to the touchingly intimate, place each tale in a modern context, allowing the reader to contemplate the contemporary implications of the story alongside its ancient origin.

The editors acknowledge that the weakness of the project is the language barriers—a difficulty often faced in this column as well. All of the responses come from English-language teachers, and readers are thus deprived of some of the richness that comes with a more global perspective. A sequel to The Hidden Lamp could include non-English teachers in translation.

The book is divided into four sections, each dealing broadly with a different theme: the first section, stories of “seeking and awakening,” deals with the attainment of insight; the second focuses on “being human” and reveals koans of unexpected hilarity, sexuality, and earthiness; the third section focuses on gender, and the supposed limitations of the female body; and the fourth on service and practice. The first section contains perhaps the most traditional koans, including the wonderful story of Chiyono, a servant girl who attains enlightenment when she drops her water bucket. The third section is the most overtly political, and several of the writers touch upon issues of gender imbalance, patriarchy, and the non-duality of gender.

My favorite section is part two, in which the women in the koans burn down houses, stick monks’ faces into their crotches, and bury their children. “Being human” is indeed rich material for consciousness-raising. I laughed out loud at the story of Miaozong, from 12th century China. To convince a doubtful monk that she deserves to study the scriptures, Miaozong bares her body to him, exposing herself as the source of all Buddhas—all practitioners start out as babies, crossing the threshold of a woman’s body. When the monk asks to enter, Miaozong replies, “Horses may cross; asses may not.”

The reflection to this funny and shocking koan comes from Hoka Chris Fortin, who recalls a reenactment of the tale during retreat. She writes that pretending to be Miaozong in the skit made her realize that many of her previous Dharma ancestors had been male: “I had never before been consciously aware of how some part of me was subtly and perpetually changing from a women’s body into a man’s body in order to fully engage with the teachings,” she writes. “Miaozong’s unbounded confidence in the pure Dharma body of practice, and her embodied faith in the sacredness of a woman’s body, resonated through me like a dragon’s roar.”

This is perhaps the best use of The Hidden Lamp; as a stimulant for Buddhist practice. The editors provide a list of ways in which the koans can be used, but the stories themselves are evocative and provocative enough to speak for themselves. Dipping a toe into the “endless life-giving stream of women” in the stories, the reader can sit with the koans as practice or let them slide away into the endless stream.