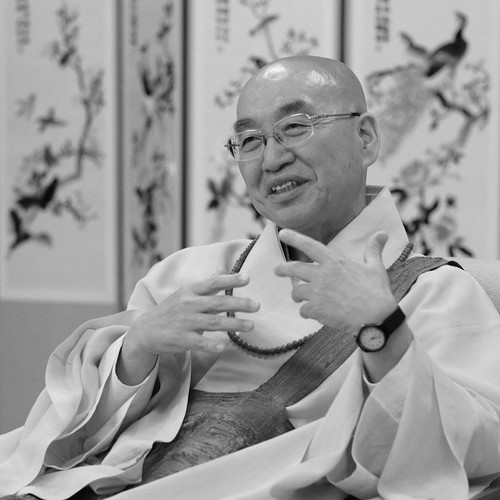

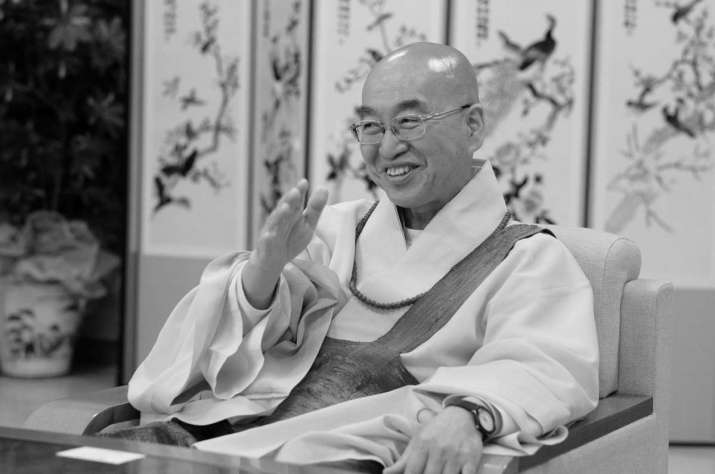

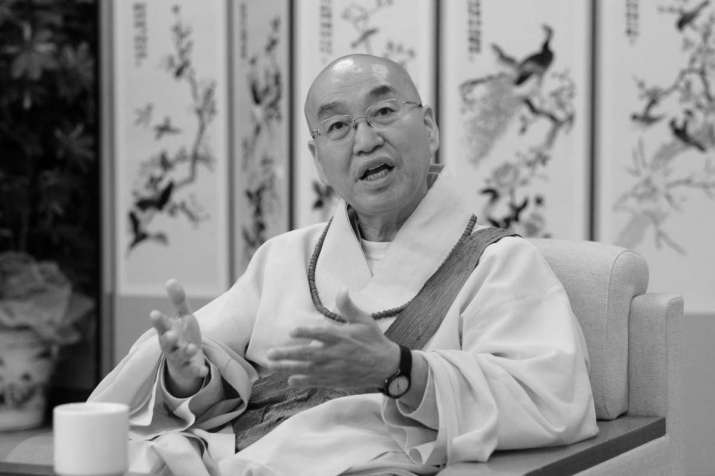

Korean Seon (Zen) master Venerable Pomnyun Sunim* (법륜스님) wears many hats: Buddhist monk, Dharma teacher, author, environmentalist, social activist, and podcaster to name a few.

Since entering the monkhood as a novice in 1969 and being fully ordained in 1991, Pomnyun Sunim has never been one to shrink from a challenge or shun adversity. He has founded and led numerous initiatives and movements founded on the Buddha’s teaching to respect all living beings, including ecological awareness campaigns, promoting human rights and world peace, and the eradication of famine, disease, and illiteracy. He has been a tireless voice on the dangers of environmental degradation, and against societies and lifestyles based on overconsumption, and has engaged in humanitarian and human rights efforts at home and internationally.

In 1988, he founded the Jungto Society, a volunteer-run humanitarian organization that aspires to embody the Buddhist teachings through social engagement and by promoting a simpler lifestyle in which people consume less. The Jungto Society seeks to address the problems and crises of modern society by applying a Buddhist world view of the interconnectedness of all things and the principle that everyone can find happiness through Buddhist practice and active participation in social movements.

Pomnyun Sunim has actively engaged with North Korea for many years, campaigning for peace and supporting North Korean refugees through the provision of clothing, food, and medicine. In the wake of a crackdown on such aid efforts by the Chinese government, which resulted in the detention of Jungto members, the organization now focuses on assisting North Korean defectors already settled in South Korea, providing counseling, and guiding them on cultural and social acclimatization.

A regular speaker at public venues such as community centers, libraries, universities, and churches, Pomnyun Sunim is renowned for his sharp and insightful Dharma dialogues, offered free of charge and expressed in simple layman’s terms, with the aim of sharing his Dharmic message of happiness and freedom with people from all walks of life, backgrounds, ages, and religious affiliations. He extends his reach to audiences and practitioners across the globe through YouTube videos and podcasts.

Pomnyun Sunim has also had a major impact through his numerous books and written commentaries, which include The Harmony of Work and Buddhist Practice, Class for Mothers, Commentaries I and II on the Diamond Sutra, Looking for Happiness in the World – In Search of a Hopeful Paradigm for Society, and A Treatise for Young Buddhist Practitioners.

In recognition of his invaluable humanitarian achievements, Pomnyun Sunim was a 2002 recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Peace and International Understanding, which has been called the “Asian Nobel Peace Prize.”

Buddhistdoor Global: Sunim, many of our readers will already know you as an outspoken advocate of socially engaged Buddhism and the founder of the Jungto Society, the Join Together Society, Good Friends, and The Peace Foundation, among others. Could you describe what first drew you to Buddhism and motivated you to become a monk?

Venerable Pomnyun Sunim: Growing up, I actually wanted to become a scientist. There was a Buddhist temple next to my school and during my first year of high school the monk in the temple recommended that I become a monk. I rejected his offer at the time because I thought that religious leaders weren’t very realistic—in Christianity it’s taught that a baby was born to a virgin mother, while in Buddhism there’s a story that a child was born who stood up immediately afterwards. Religions often ask people to believe these kinds of stories, but I couldn’t believe them. If they were intended as symbolic messages, I could understand, but there’s a tendency for religious leaders to make people take these kinds of tales literally. I didn’t have any trust in those stories, so I told him that while I was happy visiting the temple, I didn’t want to become a monk.

One day, near the end of the school year, I was preparing for my exams so I went to the temple to pray to the Buddha hoping to get good results. Because the monk was a great talker I usually tried to avoid him while I was preparing for my exams, but he saw me that day and called me over.

“Where did you come from?” the monk asked me, and I replied that I had just come from school. Then the monk said, “No, before that, where did you come from?” And I replied that I had been at home. So the monk went on, “No, no, before you were at home, where were you?” He continued asking these questions until I finally had to answer that I had come from my mother’s womb. And once more the monk responded, “No, before that!” And I replied, “I don’t know . . .”

And then the monk asked me: “Well, where are you going?” And I replied that I was on my way to the library. “And after that?” he asked. I said I would go home. “And after that . . . ?” Eventually, after many questions, I told the monk: “I’ll die.” And so the monk asked, “And after that?” And I replied, “I have no idea . . .”

Suddenly the monk shouted at me: “Well why are you so busy if you don’t even know where you’re from or where you’re going?!” That gave me a big shock and I was speechless for a moment. Then I asked him, “Is there anyone who knows the answers to those questions?” And he replied, “Everyone should know.” So I asked him, “How can I know the answer?” And the monk replied, “Come and live with me at the temple.” And that’s how I ended up becoming a monk!

BDG: The Buddhist path is often framed as a very personal, internal journey of insight and realization. In your view, how does this internal practice translate into outward action, especially as manifested by engaged Buddhism?

VPS: Most people don’t live their lives on their own, based on their own strength. Other animals, such as squirrels or rabbits, live according to their own strengths and abilities, but humans tend not to. People often ask for help—from other people, or from God. That’s why people complain and are often in pain, because they’re always asking for help and when help doesn’t come they start to suffer. And that’s how they begin blaming other people.

Many people assume there is an almighty God who will listen to their wishes—that’s how they pray, to some kind of mighty force. This makes people feel dependent on God for their lives, and they lack the strength to live for themselves. So the first thing people need to do is to learn how to become independent beings. If rabbits and squirrels can do it, then so can humans!

People’s suffering often originates in their own greed and desires. When they learn to let go of their desires, then there’s no need to pray to God. People need help not because they’re weak or inferior, but because they are greedy; they have unfulfilled desires. The first cause of suffering lies in desire. The second problem is the ego—thinking “I am right,” or anger arising from the thought that “I am right.” The third problem is ignorance, which turns a blind eye to the truth. These are the true causes of our suffering—not because we are inferior beings.

But we can help people lift themselves out of suffering by helping them realize these causes of suffering. When people study the Buddhadharma, they can lift themselves out of suffering. The majority of people use their energy giving themselves a hard time, but when they need to they can convert that energy into helping others. When they begin to help the hungry, then they start to care about people or children in hunger-stricken countries, when in the past they only cared about their own children. They also start caring about the environment. Then their lives begin to change from “I want to get help from society” to “I want to help to society;” there’s a shift in perception.

The easiest way to help society is to give money. Giving time, volunteering is a little more difficult. That’s how we encourage people to engage and do something for a good cause. Then people will find themselves confronted with questions about what aspects of society they want to change. The easiest way is to help those in need. The second way is to do something to mitigate environmental degradation. A more advanced level is to engage in peace activities, because this has a political aspect. The word peace is a neutral term, but when people begin engaging in peace activities, it becomes a political issue, which makes it a little more difficult. The next step is to advocate for civil rights, for example encouraging people to vote and making them realize that we are the masters and owners of our countries—not the presidents or politicians, who are the public servants to whom we delegate the right to govern.

One of the main teachings of Buddhism is that we reap what we sow. There is a cause when something happens, and there are conditions that dictate the effects: the effects will come when the cause meets certain conditions. It is really important when we sow seeds to be mindful of what kind of seeds they are. But the conditions under which the seeds are sown are also important. Sowing seeds can be compared to the internal practice of individuals, while environmental conditions, including soil, moisture, and temperature, can be compared to the environment in society. The results come when the seeds meet the soil. If one aspect is ignored, then the result will not be good.

If people think only internal practice is important, it is similar to focusing on the seed, while ignoring the nutrition of the soil. In other words, social environment and internal practice go hand in hand. That is the essence of the Buddhist teaching. However religions tend to focus on only one aspect, and can go to extremes because of this tendency. In social movements, people often focus on changing the structure of society while ignoring internal practice. But the Buddha taught that those two aspects should go hand in hand; they cannot be separated.

About 2,600 years ago, the Buddha made a statement like this, but over the years Buddhism has changed and many people focus only on the internal aspect while ignoring the environmental aspect. I believe we should go back to the true meaning of the Buddha’s teaching; not Buddhism in terms of religion, nor in terms of philosophy, but back to the religion in terms of the practice and lifting ourselves out of suffering. It’s not about knowledge, it’s not about belief, it’s about realizing the truth so that we can move toward attaining Nirvana.

At the same time, we can’t help but move in the direction of changing society for the better. In modern terminology this can be called engaged Buddhism, but I don’t believe that engaged Buddhism is a new concept—it’s already there in the teachings. We should go back to practicing engaged Buddhism as taught by the Buddha 2,600 years ago. That is why I help people to lift themselves out of suffering.

But we cannot stop there—once we are out of suffering, we should act to help other people out of their own suffering. The first step is to share the Buddha’s teachings with other people. There are people who don’t have the opportunity to listen to the teachings and we need to improve the social environment so that more people can learn: if people are hungry, they should be fed; if they’re sick, they should receive medical care; if children are uneducated they should be given the opportunity to go to school; if there is discrimination based on race or gender, then they should be protected. This is the principle behind my activities.

BDG: In 1988, you founded the Jungto Society as a grassroots organization based on Buddhist principles. Jungto is now active in numerous humanitarian projects. What is the philosophy behind this movement?

VPS: By integrating my two concerns—educating young people about Buddhism and social movement activities, I established the two principles of my work. However there were no detailed teachings in the Mahayana scriptures, and Seon Buddhism only highlighted internal practice for individuals. I couldn’t find any references to education for teenagers or social movements in the Buddhist texts. So I decided to approach the Buddhist teachings at their core.

I dug deep to find out what the Buddha was like and started studying scriptures that describe the Buddha: What did Indian society looked like when the Buddha was born? Why was the Buddha suffering in the environment that he was born into? Why did he decide to leave the secular world? How did he engage in his practice? What were his concerns during those six years of ascetic practice? What was his realization? What was his attainment? When he first met his disciples, what were his first teachings? What was his life like? He must have encountered many obstacles over the course of his life; how did he overcome these difficulties? Why was it inevitable for the Buddha to face these external difficulties and obstacles? I started conducting in-depth research into this. He was not a special human being, he was not a god-like figure, but he couldn’t help but choose the path he took because he wanted to address the most contradictory aspects of society in India.

During my research, I realized that I, too, had been exposed to a very contradictory and distorted Buddhism because the Buddhism I was taught lacked the social aspect that was emphasized by the Buddha. It was a very empty-sounding philosophy that didn’t engage with society. So I started asking whether this kind of religion or philosophy could be of any help to people who are suffering, who are in need. The religion existed as a vested interest in society—it didn’t provide any solutions for crucial social issues. There are many Buddhist cultural heritage sites in Korea, but Buddhism only existed as a heritage or a tradition, without offering any practical help to people. I think the same situation can be found in other religions. So I believe that we should go back to the concerns of the Buddha by adopting Buddhist principles to resolve our current issues.

BDG: You have been actively promoting peace between North and South Korea for many years, and campaigning for the rights of Koreans living in the North. In the wake of the historic summit between South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korea leader Kim Jong-un on 27 April, and the subsequent meeting between Kim and US President Donald Trump on 12 June, can you share your thoughts on the path to peace?

VPS: Since the Korean War ended, we have been living under an armistice treaty. Several attempts have been made to disassemble this cold-war structure, but all of them failed. There are people who are not very optimistic about the prospects for peace because we’ve only experienced failure before. However, I believe we are very close to success because we have only experienced failure before. We failed in the past because we thought it would be easy, we applied overly simple approaches. But by learning from our failures we can plan our approach more carefully.

The situation in Asia is unfolding very dramatically on many different levels. Due to the rise of China, we exist in an environment of competition between the China and the US, and the global order is being re-established. We could easily fall back into war and hostilities, or we could use this opportunity to resolve age-old conflicts. My concern is how to reduce the risks while increasing the opportunities. Trump has brought us both risks and opportunities; I think the possibility is 49:51 of risk versus opportunity, so we are more likely to move toward peace. If peace can be established, then security and order can follow, not only on the Korean Peninsula, but throughout East Asia.

What is most important at this point is to implement the detailed agreements that have been drawn up between the two Koreas. In the Jungto Society we have been praying for 1,000 days to end the war and create peace. In 2017 we held two peace rallies in the presence of 10,000 people, and in March we sent a petition signed by 100,000 people to the White House calling for an end to the Korean armistice and a peace treaty.

If North Korea is willing to open their door, we will provide humanitarian assistance. However the human rights issue in North Korea is a very thorny one. We are already involved in helping North Korean defectors living in the South. However, the question now becomes how to improve the situation. It will not be resolved by criticizing the North Korean regime—they will be the ones to actually improve the situation, so the question is how we can resolve this issue in a gradual manner in cooperation with the regime. The North Korean government’s priority is security, not human rights. Once security is guaranteed, their second priority will be economic development, and then we will be able to raise the issue of human rights. This will inevitably cause conflict and differences of opinion between our governments.

What’s different about our organization compared with other humanitarian groups is that they want to focus on bringing down the North Korean regime, but we acknowledge their system and we believe that their system should be maintained and then when we can raise the human rights issue—it becomes a matter of their own choice and will be determined by their people. However, I also believe that we, as outsiders, must raise the issue of human rights because the protection of human rights is guaranteed under North Korean law, but it’s not implemented and people are suffering there.

BDG: As we head into the 21st century we see an increasingly unstable and politically divided world. How do you view the role of Buddhists and engaged Buddhism in this era?

VPS: The impact of engaged Buddhism is limited at the present moment, but it will grow and should grow in the future, and I’m willing to play a role in this by engaging with the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB), with which I’ve been involved since 1993. However, I live in Korea and my main concern is Korea’s situation. I’m going to conduct my own experiments in Korea by setting precedents and successful examples here. Once a model is successfully established, then the next generation can easily adopt that model at the international level.

The first issue is alleviating the suffering of individuals in the modern world. There are many successful examples of this. I’ve seen countless individuals lifted out of suffering through their internal practice, or their practice with Dharma teachers, or simply through listening to Dharma talks—my own YouTube channel has about 100 million views. Many people have told me that my Dharma talks saved their marriage, or saved them from the brink of suicide, there are many similar accounts. And its irrelevant to religion; people of different faiths can also listen to my talks. Our goal is to move beyond YouTube and find different ways of making happiness more available the public.

Unfortunately, some people are skeptical about the identity of our movement because it can’t be easily defined as a religious or a social movement. We are playing a crucial part in the movement to establish permanent peace on the Korean peninsula, which has been going on for quite a long time. Although the scale of our movement is fairly small, I want to spread our way of living, our attitude toward life, to the broader public so that they can adopt our values in their own lives.

BDG: Considering the critical global situation of manmade climate change, environmental degradation, pollution, and the human impact on wildlife populations, and so on, how optimistic are you that societies can make the necessary changes at this late stage?

VPS: Really, I think the chances are very slim, however I will continue my work because human desires are not going to change easily. Convenience is addictive by its very nature so people will not give up their conveniences once they’ve experienced them. People will only truly realize the importance of the environment when people start dying in large numbers, or when there’s a major example of permanent and irreversible damage to the environment.

So there are two goals in this respect. The first is to reduce the rate of human damage to the environment. The second is to create a model for society for the next generation to live harmoniously after the irreversible damage has already been done. If there’s a model, then there can be hope for the next generation—a model in which people don’t merely follow their desires. If there’s a model for society in which we can acknowledge human desires but don’t simply follow them, it will be more sustainable. My concern is to create such a model, even at a small level.

We have already created this type of community in the Jungto Society—it’s not closed at all; it’s open to the public—and people living in that community are not chasing their desires. They don’t consume very much, they are very satisfied with their lives. They also contribute to society so they have a sense of a rewarding life.

I get a lot of questions about whether I think this can be successful on a larger scale. But it really doesn’t matter from the practitioner’s point of view whether it is a success or not, because I can’t help but take that path as a practitioner. If it’s a success, then I will be grateful. If we fail, then the next generation can continue the work and take the lessons we’ve learned to create success eventually. Our job is to take those first few steps that the next generation can follow at another level.

* Sunim is a Korean title of respect for Buddhist monastics.

See more

Pomnyun

Jungto Society

Join Together Society

The Peace Foundation

EcoBuddha

Venerable Pomnyun (YouTube)