I recently had the great fortune to visit Mexico City for the first time and was impressed by the variety of art and architecture—two of my favorite things in the world—in this fascinating place, and especially by the range of depictions of the female, the feminine, or one could say, the dakini Mexicana. Mexico has a lively, rich, and fraught history, much like the United States. It is a complex tapestry of political, religious, and cultural collisions resulting in a diversity of expression.

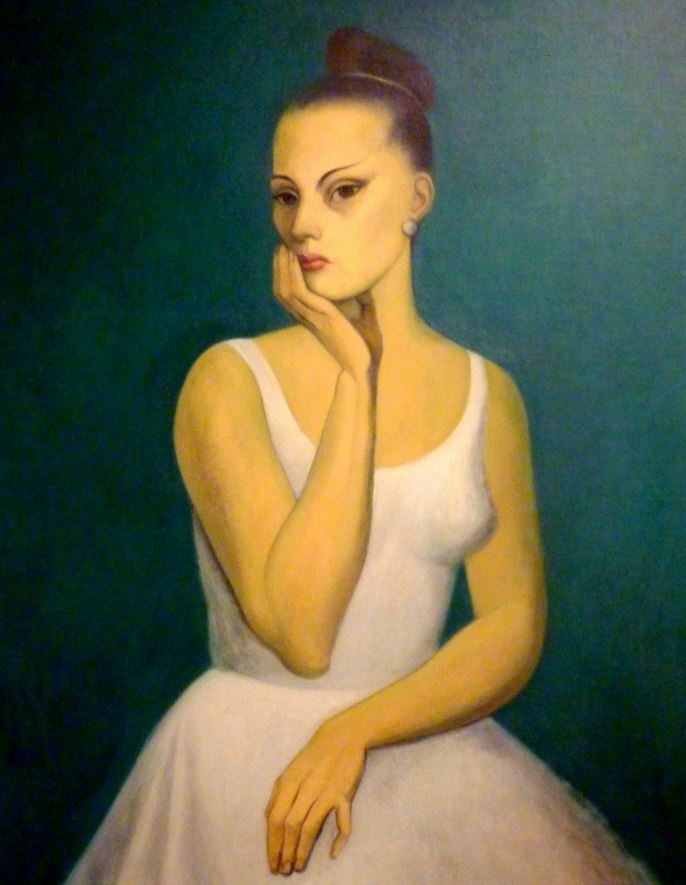

My first stop was the Castillo de Chapultepec, site of a famous battle in 1847 between Mexican and US troops. Six Niños Héroes, or young cadets, died bravely rather than surrender. This site is built upon an ancient Aztec retreat place, existent since pre-Colombian times. The Castillo of present day is a tourist attraction with stunning stained glass windows and murals depicting various goddesses. In the garden stands a large statue of a shawled woman supported by male figures surrounding her column. Everywhere I turned were depictions of the female figure: mother, saint, goddess, leader, seductress, performer, and the royal inhabitants of the Castillo in days gone by.

Photo by Sarah C. Beasley

In the Palacio Nacional, the Museo del Arte Moderno, and in many public spaces I encountered moving images of mother and child, sometimes the Madonna archetype, yet often a nameless peasant woman. This female image is iconic in almost every culture, yet in Mexico has its own unique forms of expression, styles, and depictions.

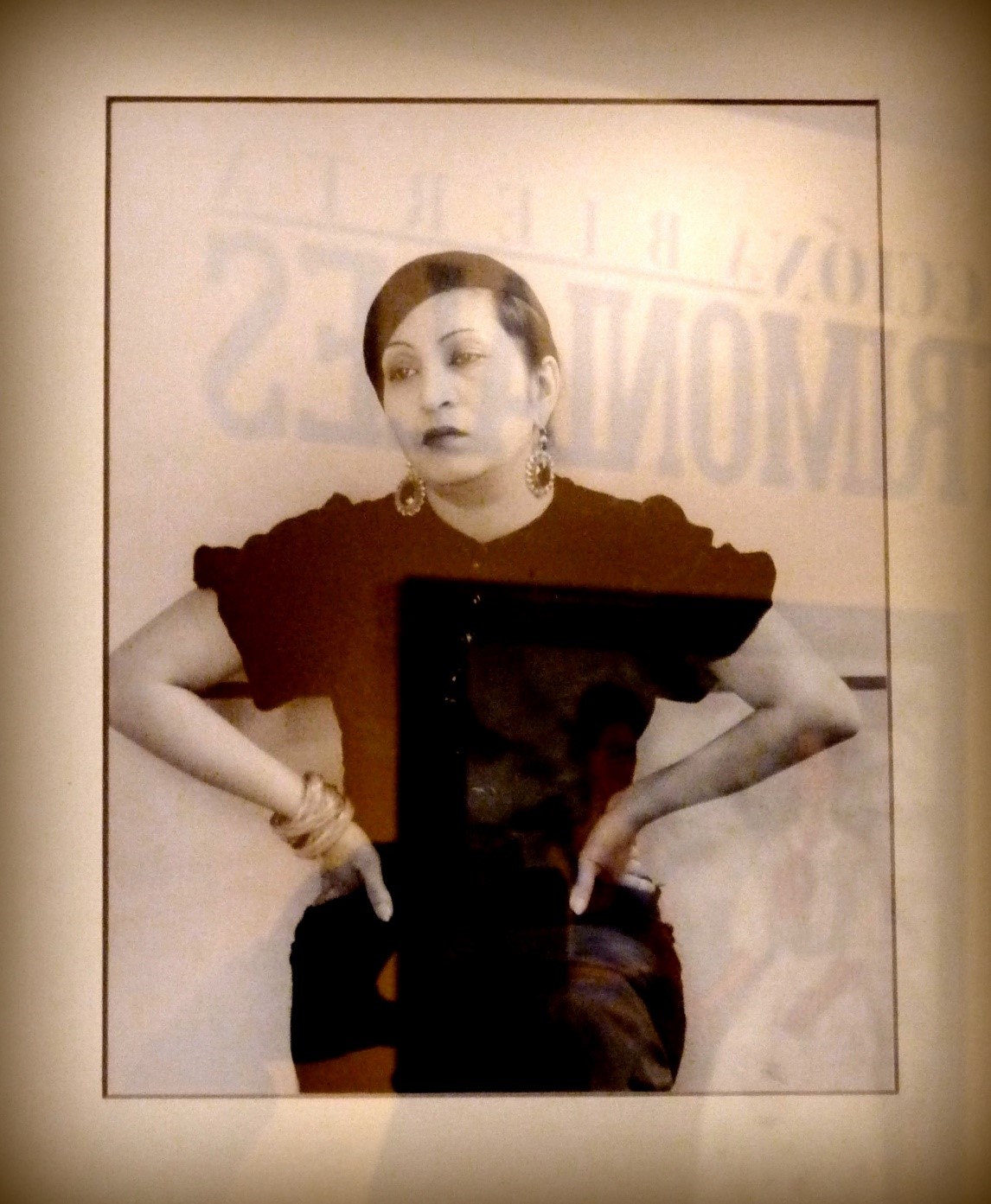

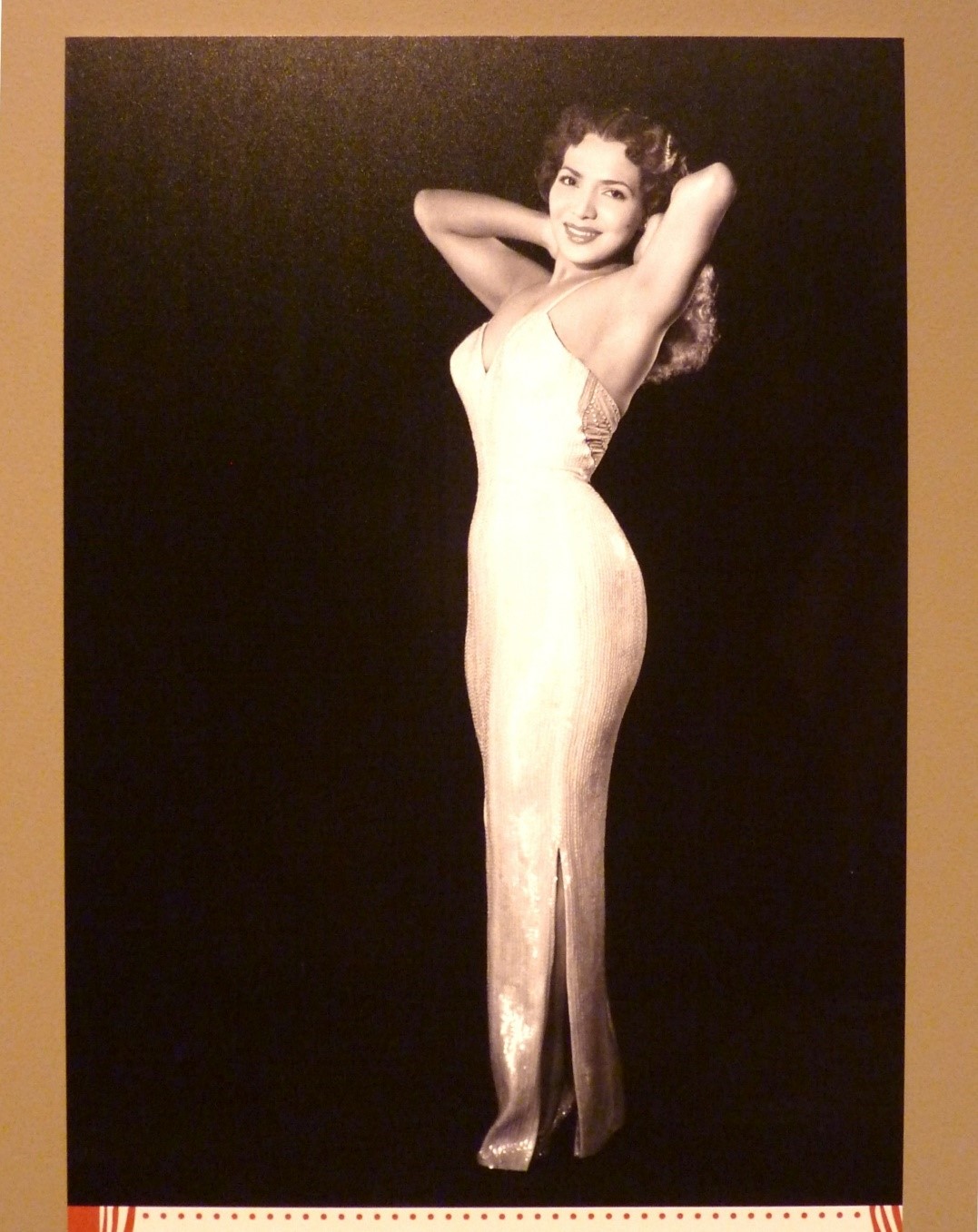

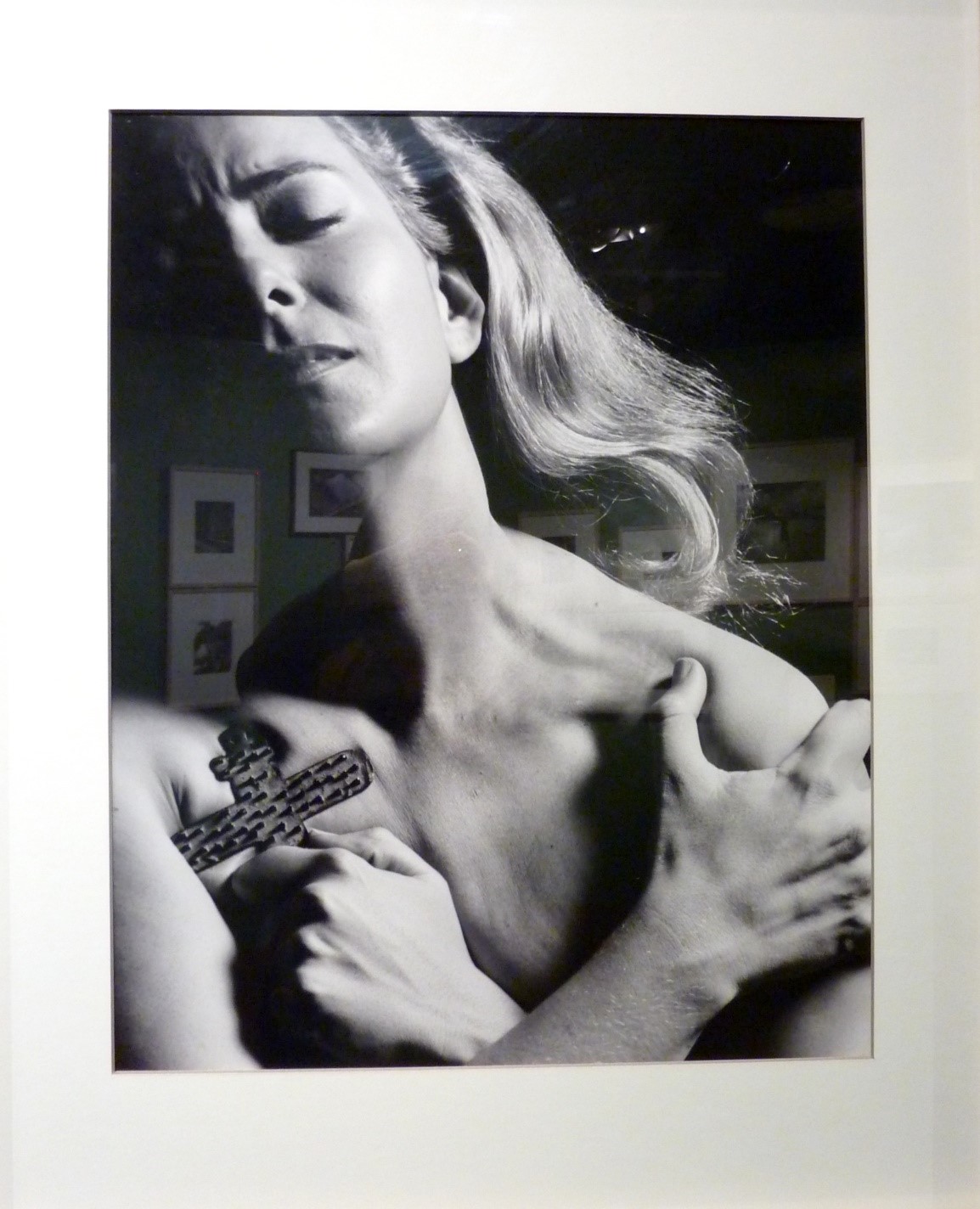

Some of the images I enjoyed most were photographs of historical women of all kinds—political figures, community leaders, artists, and performers in many genres. A strength, presence, an intensity, grace, and beauty; these are just some of the many facets of the soul of the Mexicana.

Palacio Nacional. Photo by Sarah C. Beasley

By contrast, an exhibit in the Palacio Nacional of burlesque dancer photos from the 1950s and 1960s showed a very different side of life, complete with peep-windows onto reconstructed dressing rooms, and elaborate costumes and headdresses. It is hard to imagine that era in our overwhelmingly technological world today, but these shows clearly brought live entertainment to new heights and produced a whole generation of both performers and audiences who adored and worshipped not only the female form but costume and dance as a grand art form.

I spent time in the grand cathedrals of Mexico City, enjoying traditional iconography and the atmosphere of reverence and prayer. In the street vending stalls and art galleries, as well as in church, one encounters images of Mary and the Virgen de Guadalupe, patron saint of Mexico, everywhere in sight.

Modern women in Mexican culture are as diverse as can be. Singer and songwriter Natalia Lafourcade is a strong, vibrant, and feminine example of a modern day musician and holder of traditional popular culture for young and old Mexicans. Her work straddles past and present as she composes and plays with elder musicians of previous generations, yet her music speaks to the present, younger Mexicans as well, as pride in folkloric music and dance finds a resurgence.

The Aztec Concheros dancers in the Zócalo plaza remind one of days gone by and the tenuous continuation of an ancient culture amid modern society, with all the complexities of culture and economy, as well as religion and language, that accompany the clash of civilizations we are all too familiar with today in North America.

From the Virgin Mary to the burlesque dancer, to the artists and performers of contemporary Mexico, the soul of the Mexican dakini is alive and well in all her many forms of display.

See more