Ekphrastic: from the Greek ἐκ (ek) and φράσις (phrásis), “out of” and “speech,” respectively, and the verb ἐκφράζειν (ekphrázein), “to proclaim or call an inanimate object by name.”

Ekphrastic poetry has long been used as a means to verbalize something visual. When we are deeply moved, poetry often becomes a most effective way to sink fully into, feel, and articulate our otherwise tacit internal responses. We are painting with words. We are dancing with words. We are traveling with words. We are coming home with words.

I know people who are polarized in their opinions of poetry, however. And I confess that I, too, can struggle to read through what I consider to be pseudo-clever, overinflated, pretentious twaddle set to rhyme. But hey, that’s only my opinion and counts for nothing to the author. Poetry should never be a popularity contest nor a competition; I don’t doubt for a second that others may have secretly thought the same of my own poetry. If the poem means something to us however, that is all that really matters. By the same token, reading someone’s poem can feel like floating through someone else’s reverie, or being a hostage on someone’s rollercoaster ride. A poem can remind us of our commonalities; our shared values, experiences, and dreams. In a few short words, a poem can transport us to distant times, lands, and topographies of the mind. If school put you off writing poetry, the teachers ought to be ashamed. It may not be everyone’s passion, but it has a magic that should be appreciated. Also, as I point out to the younger people in my life, any decent rapper or lyricist must be a poet. Songwriters are (or should be) poets who put their words to music.

But writing a poem can still be a daunting prospect at best, and at worst, a pointless exercise. The thought of piecing together words that we think should rhyme or express a rhythmic beauty or depth that impresses is off-putting to many. But as the haiku poetry of Japan shows us, in only three, unrhymed lines we can express profound beauty that can open our eyes to a new feeling or comfort us with a safe familiar one.

If it feels right for you, I invite you to use poetry as a form of meditation.

The science of the relationship between how we feel and our health is well documented, though I urge those for whom the concept is new to do a little research. Suffice it to say that when stress levels are lowered, our body reduces its inflammatory responses and our immunity improves. Occasional stress may well be a very necessary response to circumstances in the immediate moment—such as fleeing in the face of a particularly grumpy bear—but chronic stress is disastrous to the immune system. This is one reason that secular meditation is so advocated today, as settling the mind and regulating the breath tells the brain that all is well and to relax. In this relaxed state our body can focus on keeping healthy. Blood flows freely to the organs and gut, rather than to our legs, ready to run. And we are better able to respond to the world. However, I propose a poetic meditation that will help at a deeper level.

Ekphrastic poetry is an incredible way to deep dive into a relationship with an image, with the subject of the image. It becomes an intimate voyage into aspects of the image, of the icon, of the energy of the deity, that may have otherwise escaped your notice. Within this engagement we can tap into personal insights that may have profound value to us.

Over the next few weeks, I propose the daily creation of a short poem pertaining to deity. We will stay with one deity for as long as feels comfortable, though aiming for at least a week will offer deeper benefits. This exercise can help bring us closer and deeper in relation with deity as well as the sacred within ourselves than we could possibly imagine.

No doubt the first few days may feel tough. Words may leave the building, leaving you staring at a blank wall. However, keep going. It’s like turning the key in a rusty old lock; continued practice will eventually have the door open and the fresh air and open horizons will flood in.

In these strange days of contagion, meditation on Parnashavari may be a very useful deity and energy to draw in for the benefit of all. However, to begin with, focusing on a beloved deity will help both the poetry exercise and deepen your relationship with it.

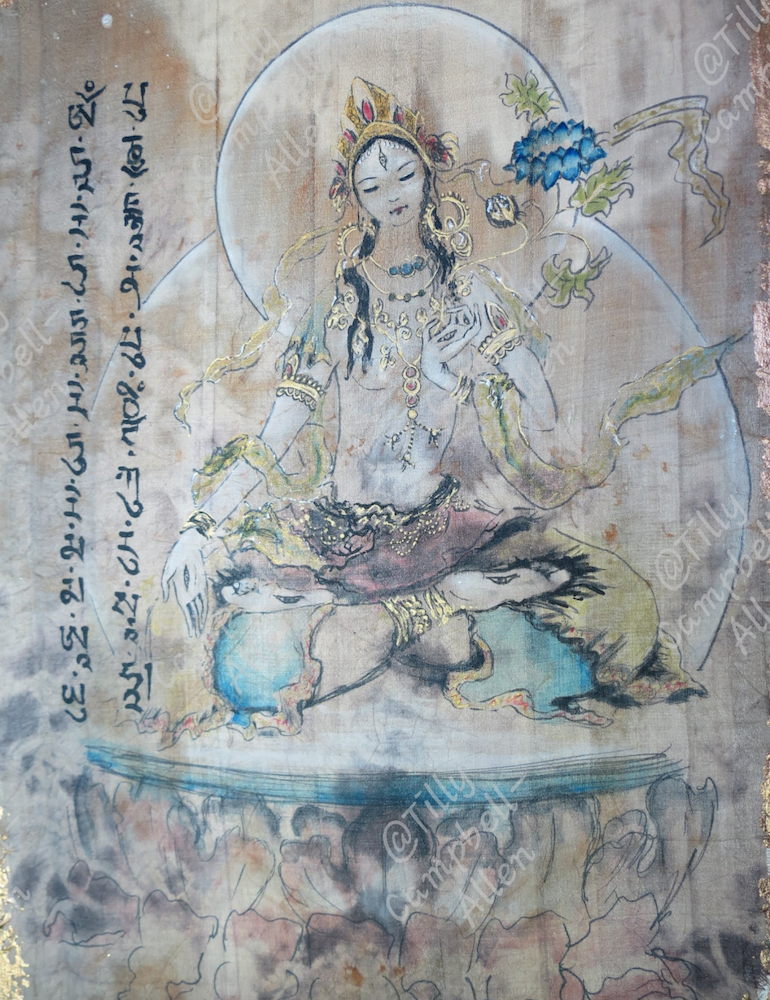

Let’s say we decide to work with White Tara for the next 7–10 days. I have included some paintings of Her with this article that express different aspects of Her nature. You can use the same image or swap between images of her as you feel appropriate.

With a notepad and pencil, sit with one of the paintings and lose yourself in Her. Really melt into Her. Transport yourself into the mindscape of the image before you. Feel energy flood your being. You may experience this as a sense of growing excitement swelling up from your lower abdomen, or as a tingling sensation all over your skin, or a cascading cosmic waterfall of stardust washing over you like the most refreshing bath. It may be that you don’t experience any visceral response at all, and that is also perfectly normal. Continue to feel into who She is; how She presents Herself in the image; the qualities that she possesses and how some of those qualities are represented pictorially. How do you relate with the colors in the image? Celebrate Her attributes, Her nature, and the nature of the elements that surrounded Her in each painting you work with. If there is water, celebrate the water qualities. If there are any celestial qualities, celebrate them. Celebrate the qualities of any nature that may surround Her. Celebrate the golden radiance that may illuminate our very being or the soft lunar glow enveloping us through the darkness. Celebrate any animals that she may have with her—what do they symbolize? And what do they mean to you? What does She mean to you? And how does She makes you feel?

However you feel as you sit with Her, let the words arise naturally. Write these words and phrases down in your notes as you feel ready, though these words may well fly away so it’s best to write them as they come but with as little disruption as possible to your meditation. As you mentally merge with the image, let the words form phrases. By now, start to consciously formulate lines of poetry based upon the feelings that have been elicited. Let the inspired words rise like bubbles into reality, like silk slipping over your lips. Like floating in space, like melting honey into tea, like boarding a runaway train. Like solving a whodunnit mystery.

One day, your poem may take the form of a haiku, the next day you may fill a page with perfect rhymes. To begin with, maybe aim for a simple four-line format with rhymes on lines 1, 2, and 4, and extra syllables on line 3 as a nice way to oil that rusty old lock. But ultimately, it’s entirely up to you.

Note the date of your poem and, if you wish, log any extra journaling on the reverse of the paper. This diary part can be interesting to look back on in relation with the poetry, but not essential. You may even feel inclined to decorate your poems with border motifs, illuminated letter work, or your own illustration of the deity. Do what feels right for you.

Keep your work together in a sacred place.

Most importantly, however, let the attributes of the deity that you have elucidated in poetic form from the wellspring of your conscious and subconscious mind, merge, and reside within you.

After the week or so of working with white Tara, when you feel ready, move on to an icon of your choice, and do so in the same fashion: try and stay with them for at least a week, writing a poem every day. This practice can excite the caudate nucleus, a key part of our pleasure and bliss area of the brain. This is often why veneration of sacred art can elicit responses such as rapture.

To understand more about how imagery can affect us, you may find these previous articles of interest:

In next month’s essay I will reflect a little on this work and then I’d like to discuss a relatively unexpected contender in the therapy market that continues to grow in availability and popularity, yet has been around for as long as humans have realized they could: I will discuss coloring in. And why this deceptively simple act can be of great benefit and help us focus and heal.

See more

Tilly Campbell-Allen (Dakini as Art)