Bhutanese journalist Sonam Dema recently spoke with the revered lama, filmmaker, and author Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche. Their conversation focused on the Buddhist view on biodiversity, respect for wildlife, and ecological conservation.

Sonam Dema: According to science, biodiversity is the most important factor for human survival and for the world to function and thrive. What is Buddhism’s perspective on biodiversity?

Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche: I can say with confidence that the Buddha is the first being on this Earth who realized and showed us the dependent nature of all phenomena. And this was 2,500 years ago, long before human psychology even conceived of the modern concepts of biodiversity and conservation.

The Buddha’s understanding is the very root and essence of biodiversity. Thus, the very survival and existence not just of humans but of all beings depends entirely on causes and conditions. This is not something lofty or moralistic, and it is not only about “good” or “bad” deeds. Rather, the Buddha taught that we’re not separate and independent beings and species but that everything is dependent on everything. So of course, we’re not separate from other species and beings.

The most quoted line in all the Buddhist teachings is that everything is conditioned and that there is nothing that is not a condition or conditioned. Among all this conditioning, the most important is the conditioning of mind. So having the right mindset to save biodiversity, not just for the survival of human beings but for all beings, is paramount.

SD: Buddhists believe in various realms of gods, humans, animals, and spirits. Does being born as an animal—for example, a tiger, a golden langur, or a fish—suggest that this is a result of past “bad” karma?

DJKR: Buddhists do believe in different realms, but this is not like the Christian ideas of heaven and hell. For example, the different realms are often taught psychologically, which means that a person can actually go through all the different realms in a day—sometimes experiencing godly pride, and at other times human greed, hellish aggression, the miserliness of the hungry ghost realm, and so on.

Furthermore, “bad” and “good” are completely relative concepts. So, what you call “bad” karma or “good” karma is also entirely subjective and relative. It could be argued that some human births are much worse karma than being born an animal.

Buddhists often cite the notion of “precious human birth” to show that the human body, if used properly, can be a precious vessel. That view is based purely on humans having the capacity to feel sadness and awkwardness, and therefore yearning for the highest truth. And this means that they have a chance or opportunity to acquire that truth, which most animals don’t have simply because they are so busy just surviving.

SD: As human beings, are we superior to animals? Does this also mean we have the right and freedom to mistreat animals, domesticated or wild?

DJKR: As I just said, that supposed superiority does not apply to all human beings. Only those who seek the truth have what we call a precious human body. The great poet and saint Milarepa sang a song to a hunter expressing his realization that not all human beings have a precious human body.

You also ask about “right” and “freedom,” but these seem to be very monotheistic concepts that we find in Abrahamic or Christian traditions. In Buddhism, no one has the authority to bestow rights or the right to give someone happiness or unhappiness. So no one has the right to mistreat or harm anyone. People still do so, but that’s because they are ignorant, not because they have any right to do it.

SD: Many people harbor some ill-feeling toward snakes, irrespective of whether they are venomous or non-venomous. Snakes are viewed as destructive or are depicted as dangerous in many of our traditional stories. What are the reasons we have generated a common dislike for snakes and certain other wild animals?

DJKR: Those feelings come from people’s cultures, not from Buddhism. Very many of the Buddha’s disciples were nagas, and some of the most generous patrons of the Buddhadharma were naga kings and queens. So, if snakes, spiders, and scorpions make many people uncomfortable, I think that’s more like racism and has nothing to do with Buddhism.

SD: The illegal trade in wildlife continues to be rampant, especially in Asian countries, many of which identify as Buddhist nations. What is your view on this?

DJKR: We need to think here about demand as well as supply. For reasons we don’t have time to examine here, many Buddhist countries are very poor. But many of today’s so-called rich countries became rich by robbing those poor countries for centuries. So the responsibility for the wildlife trade is at least as much on those who use the products as on those who supply it.

In any case, this has nothing to do with Buddhism, and being a Buddhist country certainly doesn’t create more opportunity for the illegal trade in wildlife.

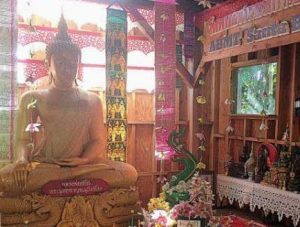

SD: Ivory is highly prized as a commodity and also considered sacred with its presence on the chosum [altars] in Buddhist temples. Does the presence of ivory on chosum bring more merit?

DJKR: Again, seeing ivory as a prized commodity is purely cultural and has nothing to do with Buddhism or with merit. After Ashoka had offered gold coins to thousands of monks, an old beggar lady one day offered some water to monks who were thirsty. When Ashoka asked the chief monk about merit, the monk responded that the old lady had accumulated more merit than was gained from all Ashoka’s gold coins.

In Buddhism, merit depends completely on motivation. With the most profound right motivation, giving even a dead leaf could accumulate lots of merit. With wrong motivation, building a whole castle out of ivory will just cause suffering to animals and achieve nothing.

SD: We also use high-quality peacock feathers in our chosum in Bhutan. Is this essential? Is there a better substitute?

DJKR: Peacock feathers are not even mentioned in any tantric text. The most appropriate and correct substance for the vase or bumpa is actually kusha grass or leaves. As I keep saying—all of this is cultural baggage and has nothing to do with Buddhism.

SD: Some Bhutanese traditional medicines require animal parts as ingredients, such as bear bile. Is this attuned with the Buddhist belief in not harming animals?

DJKR: Again, Bhutanese traditional medicine has nothing to do with Buddhism. A healing art is a healing art. Buddhism is the dharma that teaches truths such as impermanence, duḥkha, and the emptiness of phenomena. From a Buddhist point of view, forget bear bile. If a lavender herb is plucked with the wrong motivation, it goes against Buddhist principles.

SD: Can we then say that there is an urgent need to stop poaching and end the wildlife trade, and instead to work toward protecting biodiversity in general?

DJKR: Absolutely! There’s a very urgent need to stop poaching and end the wildlife trade and to protect wildlife and biodiversity. I am not a scientist, but I understand that protecting wildlife, biodiversity, ecology, and the environment are paramount.

But who is making that effort? I don’t see many people doing it. If what scientists and ecologists say is true, we will soon have no fresh water to drink, no fresh air to breathe, and catastrophic global warming. Just within my own lifetime, changes in the climate are very obvious and visible everywhere.

And yet, I see hardly anyone fighting to protect our fragile ecology. With the possible exception of The Guardian newspaper, how much ongoing front-page news reporting on ecology do we see in the mainstream media? Which country has been sanctioned because it is destroying its ecology? Which country suffers from a trade embargo because it is wiping out its wildlife? How many words to save our ecology and wildlife are regularly uttered by the political leaders of the world’s most powerful nations?

But if the scientific evidence is correct, what is the use of pluralism, universal suffrage, freedom of speech, and all the other values we supposedly treasure so dearly? They are totally useless. Led by the US, so many wars are supposedly being fought for freedom and democracy. I really want to wake up one morning and read in the newspaper that the United States and NATO are fighting some country for not protecting the environment or conserving biodiversity.

SD: Human-wildlife conflict is a growing concern in Bhutan. Farmers blame conservation policies and wild animals, such as tigers, wild boars, monkeys, and birds when they lose their crops or livestock to predators. What does Buddhism say about human-wildlife interactions?

DJKR: Humans versus wildlife, humans versus humans, humans versus machines. There is no end to conflict. A hundred years from now, when the Bhutanese are having conflicts with artificial intelligence, we will have different kinds of concerns.

SD: Can humans and animals coexist in harmony? What does Buddhism say about human-wildlife coexistence?

DJKR: In some pockets, yes, animals and humans can coexist harmoniously, like with pet dogs. But thinking that humans, wildlife, and all other phenomena for that matter, will coexist and live happily ever after, that is not how Buddhists think.

SD: As a Buddhist master, what is your advice for our readers on biodiversity conservation for Bhutan and for the world?

DJKR: Who am I to give such advice? Perhaps my answers here reflect some of my thoughts about conservation. But if you insist that I say something, I would say that capitalism must die.

SD: Rinpoche, thank you very much for sharing your time and insights.

Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, also known as Khyentse Norbu, is a revered Bhutanese lama, filmmaker, and author. His four major films are The Cup (1999), Travellers and Magicians (2003), Vara: A Blessing (2013) and most recently Hema Hema: Sing Me a Song While I Wait (2017). He is the author of the books What Makes You Not a Buddhist; Not for Happiness: A Guide to the So-Called Preliminary Practices; The Guru Drinks Bourbon; Best Foot Forward: A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Sacred Sites of the Buddha; and Poison is Medicine.

This interview, originally published by the newspaper Kuensel, is a part of new series initiated by GEF7 Ecotourism Project under the Royal Government of Bhutan, named “Mainstreaming Biodiversity Conservation into the Tourism sector in Bhutan,” which is a GEF (Global Environment Facility), GWP (Global wildlife Program), and UNDP supported project.

Related features from BDG

Energy as a Way of Life: Japanese Buddhist Priests Reflect on the Ukraine and Sri Lanka Crises While Calling for Local Energy Self-Sufficiency

The Tangles

The Practice of Nonviolence

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: Buddhism in a Divided World