I live in an old farm house in the middle of nowhere. That said, it’s pretty good as far as old farm houses go. The foundation is solid, the walls are strong, and the previous owners did a good job of keeping it in good repair.

Nevertheless, there are some improvements that need to be made. The siding is on its last legs, the landscaping needs to be touched up, and the windows are more than a little drafty.

They are the old-style windows with wooden frames that are held open with weights. They keep most of the bad weather out, and I’m grateful to have them. But if there is a strong enough wind outside, we get a nice cold breeze inside the house.

Usually, this doesn’t bother me. I knew the condition of the house, the condition of the windows, when I bought it. I knew that there would be work to do before everything was as I wanted it to be.

But every now and then, a glimmer of irritation enters my mind. Every now and then, when the wind is especially strong and the house feels especially drafty, I wonder, “Why didn’t I buy a house with better windows?”

In those moments, I go outside and take a walk. I expose myself to the raw, unfiltered weather of the countryside. I allow the wind to whip around me, finding its way into all my private places. I allow the rain to splatter my face, making it hard to see. And I allow myself to experience life without my drafty farm house windows.

Doing this helps me put things into perspective. My windows do not keep out all of the bad weather. But they keep out most of it. They do not hold all of the warmth in the house. But they hold a good bit of it.

The windows in my home are imperfect. But that does not stop them from being good.

When I think about this, I think about human life and the impossible standards we have for it. In the West, we want everyone to be tall, thin, wealthy, and objectively attractive. They must be intelligent, funny, and independently wealthy.

To be anything less is to be a failure; to be an old, drafty window on a farm house.

Some respond to the impossible standards of the Western world by attempting to tear them down. But this is a mistake. It’s like removing all the furniture from your home so that you don’t have to worry about wobbly chairs.

What if, instead of focusing on standards set for us by society—either ignoring them or striving for them—we focus on the good things we do in our current state—as we are.

What if, instead of focusing on the large worldly problems that we cannot fix, we focus on the small ones that are within our control.

So, if we are concerned about the world’s climate crisis, we can respond by planting a tree. If we are discouraged by the problem of world hunger, we can respond by making a meal for loved ones. If we are struggling with anger, we can respond by giving our friend a compliment.

As humans, we are imperfect. But our lack of perfection doesn’t stop us from being good.

And while it may be true that we cannot fix every problem in the world or in ourselves, we can fix some of them.

In the moments when we forget this—when irritation creeps into our minds because we’re not smart enough, not tall enough, not thin enough—it can be helpful to take a metaphorical walk and ask ourselves the following questions:

1. Am I a murderer?

2. Am I a thief?

3. Am I a liar?

If the answer to each of these questions is “no,” we are doing more good for the world than we realize. That’s not to say that we are not causing any harm. But, like a drafty window on a cold winter’s day, we are not letting the worst of the storm enter our vicinity. And there is real value in that.

There is value in doing the best we can, even when we know it may not be enough.

And we can help see that value by reminding ourselves of the alternatives, looking at the darker parts of human nature and rejoicing in the fact that we walk a different path, a holy path.

Because everything we do in the name of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha is holy. And even if we do not get it right every time, the world is a better place because we try.

Namu Amida Butsu

Related features from BDG

The Extraordinary Gift of Impermanence

Impermanence, Suffering, and Non-Self

Metta Corners the Market

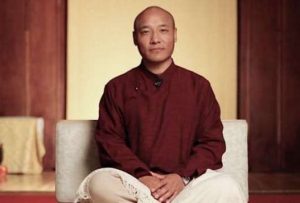

Geshe Tenzin Namdak: Living in a Material World

Smartphones, Parenting, and Struggling to Set a Good Example