Eliot Tokar is a doctor of traditional Tibetan medicine living in New York City. A practitioner since 1993, Dr. Tokar is one of the first Westerners to have gained extensive training in traditional Tibetan medicine. His published writing includes his 2008 essay “An Ancient Medicine in a New World” in the book Tibetan Medicine in the Contemporary World: Global Politics of Medical Knowledge and Practice, and he is currently featured on the Tricycle website, leading a four-part online retreat on Tibetan medicine.

Dr. Tokar began his studies in Buddhism and Tibetan medicine in 1983 while living in Amherst, Massachusetts. At the time, a friend of his was suffering from an inexplicable cluster of infectious diseases. Despite numerous visits to biomedical doctors, it was only when his friend turned to Japanese and then traditional Tibetan doctors that her health finally began to improve.

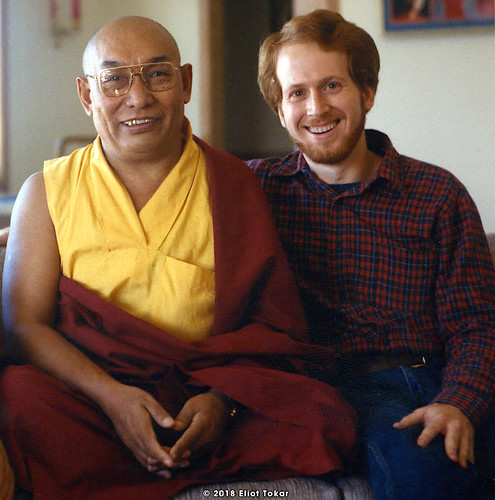

The Tibetan doctor was Dr. Yeshi Dhonden, former personal physician of the Dalai Lama. Eliot was intrigued: “Something about the ‘compassion in action’ experience that I had helping my friend appealed to certain of my core intellectual, political, and spiritual inclinations, and I felt the need to pursue them.” And pursue them he did, first with Dr. Dhonden, and then with the renowned Tibetan medicine doctor and Nyingma lama Dr. Trogawa Rinpoche.

For Dr. Tokar, medical practice and his Buddhist practice are deeply connected. “His Holiness the Dalai Lama has stated that while Tibetan medicine and the Dharma are seen as distinct, they are separate the way ‘the fingers are separate from the hand,’” he explained. “Trogawa Rinpoche put it this way: ‘My external practice is the practice of medicine. In my inner thoughts, I meditate on the Medicine Buddha.’”

This month, I interviewed Dr. Tokar about Tibetan medicine as it is practiced in North America.

Buddhistdoor Global: Can you give a brief overview of what Tibetan medicine is?

Eliot Tokar: Tibetan medicine is one of the major systems of traditional Asian medicine. It is a synthesis of knowledge regarding both health and the treatment of illness, integrating native Tibetan understanding with the traditional medical systems of India (Ayurveda), Persia (Unani), and Greece, along with influences from traditional Chinese disciplines.

Tibetan medicine is traditionally seen as a unique system distinct from Buddhism. Yet it has many fundamental influences from Buddhism and the Vedas, such as its worldview, medical ethics, and some of its understanding of physiology and pathology, for example regarding the interdependent relationship between body and mind. Tibetan medicine’s perspective that ignorance is the primary cause of suffering—such as illness—is clearly derived from Buddhist ideas. Tibetan doctors also traditionally do Buddhist meditation practices such as the Medicine Buddha, and a Vajrayana practice called Yuthog Nyingthig.

BDG: In America is it practiced as an alternative to, or adjunct to allopathic medicine?

ET: As is the case with most forms of natural healthcare in the US, Tibetan medicine is utilized either as an alternative to or as a complementary system with biomedicine, based on the discretion of individual patients. It is my experience that, typically, people who utilize so-called alternative medicine choose to avail themselves of a number of different healthcare resources that also can include biomedical interventions.

BDG: Can you describe how you approach diagnosis and treatment for illnesses?

ET: When a patient comes to my clinic, I first observe them, taking into account their personal and physical attributes. I then speak to the patient and enquire about their condition, its symptoms and development, as well as their medical history and pertinent aspects of their personal history. Dr. Trogawa Rinpoche taught that taking time in speaking to a patient allows a doctor to better understand an individual’s experience of their condition and therefore to arrive at a deeper quality of diagnosis.

I then look at a urine sample. In the urinalysis we observe such things as the color of the specimen, its odor, viscosity and after vigorous stirring the size, color, amount, and persistence of bubbles, as well as any deposits occurring within or on the surface of the sample. From this we can begin to confirm the nature of the illness, the presence of infection, and the localization of the illness, among other diagnostic factors.

Next, I feel the 12 pulses. Three fingers of the doctor’s hand are applied to the radial artery of each of the patient’s wrists. A Tibetan medicine doctor feels six pulses on each wrist, each being the pulse of a distinct organ (heart, small intestine, liver, gall bladder, etc.). We feel for many qualities of the pulse, such as its width, depth, strength, speed, and persistence. Each of those factors allows us to clearly define the illness’ etiology, its location, chronicity, hidden complications, and so on.

Eliot Tokar

To further confirm the diagnosis, we can look at the color, shape, and coatings of the tongue, specific signs appearing in the sclera [white] of the eye, and we may also test for sensitivity at certain pressure points on the body.

A patient’s treatment must be specifically tailored to fit their individual condition. Tibetan medicine doctors traditionally begin by recommending specific behavioral and lifestyle modifications. If this is not sufficient to remedy the problem, we utilize dietary therapy. If these approaches are not enough to address the condition, Tibetan medicine employs herbal medicines. If these are not adequate then physical therapies such as massage, moxibustion (the heating of specific treatment points on the body), cupping, acupuncture, herbal bath therapies may be utilized.

BDG: You mention in the online retreat at Tricycle the idea of “holism” as central to Tibetan Medicine. Is this difficult for new patients to grasp, going, as it does, against the stream of so much Western culture?

ET: Ideas about holism regarding health and illness are traditional in most cultures, including in the West. Tibetan medicine has influences—via Greek medicine—from some of the same ideas that occur in Western culture. There was a resurgence of interest in holism from the 1960s onward in the West that led to the rise of the alternative medicine and natural food movements. Looking back at how these movements changed aspects of our culture—such as goods and services that are now available as a result—we can say that they were partly successful.

But due to that success, and once conventional health, food, and medical industries grasped the economic potential of these movements, a great deal was done to co-opt them, especially beginning in the 1990s. Focus was redirected away from things like holism, a sense of compassion and common interest, and ecological perspectives, and toward individualism, lifestyle consumerism, elitism, and other New Age ideologies and mainstream behaviors.

Tibetan medicine offers a means to access a traditional [scientific] understanding of holism, especially in relation to health and illness, and their interdependence with natural law, our mind and body, and [spiritually-based] humanistic principles. The patients I see who learn and grow from what I offer them in terms of advice and treatment do very well. Those who are seeking a quick fix or a “magic” pill to instantly change their condition—that is, those who are approaching their health from a consumerist point of view—frequently do not have the willingness or patience to reasonably comply with their treatment. Where this is the case, such individuals often move on to the next “product” from which they seek a cure.

BDG: Traditional wisdom from all over the world is being lost today. Are steps being taken to preserve Tibetan medicine?

ET: Traditional medical systems such as Tibetan medicine are under great stress today in their efforts to survive and progress. They are affected by the hegemony of the biomedical and nutraceutical industries, geopolitics, economics, and ecological degradation. Additionally, the rise of statutes concerning intellectual property rights have spread a global ideology that posits cultural heritage as “property” that can be owned by an individual, organization, or nation. This commodification undermines the centuries-old practice of reciprocal sharing that built most of world culture, including its cuisines, music, religions, medicine, and so on.

If your readers wish to support cultural survival, first they should seriously educate themselves about these and other challenges to traditional medical knowledge—that is, including the consumerism that I mentioned. It is worthwhile to support both the many institutions and individual lineage holders in Asia who are teaching and practicing Tibetan medicine, as well as those of us bringing this practice to the West. It is important that senior Tibetan physicians in Bhutan, India, Nepal, Tibet, and elsewhere fully transfer their knowledge to a new generation.

BDG: Lastly, what are your hopes for Tibetan Medicine in the West?

ET: My greatest hope is ,of course, for all those suffering from illness to regain their health and achieve an understanding of “balance” in their lives. I also hope for the survival of Tibetan medicine with minimal effect from the negative forces I’ve mentioned.

Beyond that, I’ve been working for more than three decades not only to aid my patients, but to educate people internationally about what traditional medicine has to teach regarding the ecology of health and the treatment of illness. I hope that work continues to bear fruit. As with any living tradition, Tibetan medicine needs to progress and not just survive, and I hope that I will see this process proceed. We will need to remember the teachings of senior doctors, many of whom have passed. It would be of great benefit if teachings, such as Trogawa Rinpoche’s, regarding the imperative for Tibetan doctors to learn to work together across ethnicity, lineages, and institutions, were heeded.

If Tibetan doctors work together and gain solidarity from the general public and patients alike, the future can be positive. If people give in to materialism in forms such as consumerism or commodification; aggression in forms such as sectarianism or competitiveness; or ignorance in forms such as simplistic, fetishized, or biased approaches to cross-cultural communication, then we have to worry. But Tibetan medicine has survived and evolved for centuries. We should work and pray for its positive continuance and its role as a remedy for human suffering.

Maintaining a diversity of knowledge and practice is essential for traditional medicine. Although advocating for standardization might sound good, it is actually a death knell to the diversity that has provided us with enormous medical wisdom through the centuries. So please, fight for diversity, fight to maintain knowledge, and work against ignorance.

References

Pordié, Laurent, ed. 2008.Tibetan Medicine in the Contemporary World: Global Politics of Medical Knowledge and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge

See more

Tibetan Medicine: The Practice of Eliot Tokar

Tibetan Medicine: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Health and Healing(Tricycle)