War and peace

As Buddhists observe the latest manifestations of the pain and suffering of war—in Ukraine, Yemen, and elsewhere—many seek, as an expression of their faith, to aid the afflicted and work toward peace. No doubt more than a few Buddhists believe that if only more were to adopt the peaceful tenets of Buddhism, the world would be less violent. In short, most Buddhists believe that Buddhism contains within it the ability to bring peace to the world, and nothing more.

But does it?

In responding to this question, many Buddhists would immediately answer: “Of course it does! Just look at the five precepts that all Buddhists, of whatever tradition, school or lineage, whether lay or cleric, are expected to abide by. The first of them is a pledge to abstain from killing. How, then, could Buddhism be considered anything other than a religion of peace?”

The historical reality is that down through the ages there have been those identifying as Buddhists who have engaged in violence and war, justifying their actions on the basis of their Buddhist faith. These Buddhists, be they anonymous figures lost to history or recorded figures of influence and power, have found what I call “violence-enabling mechanisms” within Buddhism that allow them to justify their acts of violence. This suggests, even if it doesn’t prove, that Buddhism does indeed hold instincts for war.

The universal nature of violence-enabling mechanisms

Let me make it clear that I believe “violence-enabling mechanisms” are to be found in all of the world’s major religions. I define violence-enabling mechanisms as: “numerous malleable religious doctrines and associated praxis that, in certain situations and circumstances, can be reconfigured or transformed into instruments that at least countenance, if not actively condone, the use of violence. These doctrines and praxis are commonly, but not exclusively, activated during times of war.”

However, I do not claim these violence-enabling mechanisms are the cause of violence and war. Instead, they are invoked, typically by religious leaders, to justify or sanction believers’ participation in violence and war.

I would be the first to admit that these doctrines and praxis are often difficult to identify because, on the surface, they appear to have little or nothing to do with sanctioning violence. Which is to say that to assert that this or that doctrine has a violence-condoning “dark side” immediately provokes a strong denial from many within the tradition. These “defenders of the faith” often point to the standard or non-violent interpretation of the doctrine or praxis in question in order to deny its dark side.

In as much as I maintain that these violence-enabling mechanisms are universal, I begin with one example of these mechanisms in Christianity, although I could give similar examples from Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and so on.

A Christian example

Christians believe that God has given them an eternal soul. Moreover, they are typically promised entrance into heaven as their reward for having lived pious and righteous lives on Earth. On the surface, this teaching appears to have no connection whatsoever to religiously sanctioned violence. That is to say, how could these articles of faith possibly become enabling mechanisms condoning the use of violence?

The 17 July 2004 issue of the Cleveland Plain Dealer carried an article about Sgt. Joseph Martin Garmback, who was killed during the US invasion of Iraq. It read in part: “‘Joey loved being a soldier. He was so self-sacrificing,’ said the Rev. James R. McGonegal. ‘This man knew something about living and dying, and giving his life for someone else.’ Many dried their eyes when McGonegal assured them Garmback was going to a better place, a safer place. ‘He is safe at home, at last, at peace.’” In short, Rev. McGonegal offered a guarantee that Sgt. Gamback, who “gave his life for someone else” was now in heaven as a reward for his self-sacrificing participation in the invasion of Iraq.

This assertion is particularly questionable in connection with Iraq because, even at the time of the invasion, it was widely known that all of the reasons given for the invasion, including Iraq’s reputed possession of weapons of mass destruction, were falsehoods. Thus, while Iraq posed no threat to the US whatsoever, Gamback’s death qualified him for “eternal life.” This widely held belief among both soldiers and their families serves to promote wartime military service, in this case participation in what remains widely regarded as an illegal invasion if not a war crime.

This is only one example of how Christian teachings can serve to not only justify war but even the promise of entrance into heaven, thereby effectively turning it into a psychological weapon. This is not dissimilar to the medieval popes that sent Crusaders to Jerusalem and retake the Holy Land, guaranteeing their entry to paradise. Is it therefore conceivable that Buddhism may have doctrines and praxis that serve, at least in the minds of some Buddhist laypeople and clerics, to justify killing?

Buddhist examples

My field of expertise is Mahāyāna Buddhism in Japan, so my initial examples are taken from my research into modern Japanese Buddhism, especially relating to World War Two. Nonetheless, the latter part of this article contains many additional examples revealing the connection of numerous Buddhist doctrines and praxis to violence and war is not the preserve of any one Buddhist tradition, school, sect, or nation. It is, in fact, a pan-Buddhist phenomenon.

Buddhist statuary weaponized

In 1934, Rinzai Zen Master Yamamoto Gempō testified in defense of his lay disciple, Inoue Nisshō, who was on trial as the leader of a band of domestic terrorists. Zen Master Gempō said: “Although all Buddhist statuary manifests the spirit of Buddha, there are no Buddhist statues, other than those of Buddha Śākyamuni and Amida, who do not grasp the sword. Even the guardian Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha holds, in his manifestation as a victor in war, a spear in his hand. Thus Buddhism, which has as its foundation the true perfection of humanity, has no choice but to cut down even good people in the event they seek to destroy social harmony.” (italics mine; Victoria 2020, 122)

The following imagery of Acala, as the wrathful manifestation of Kṣitigarbha, demonstrate that Zen Master Gempō was correct:

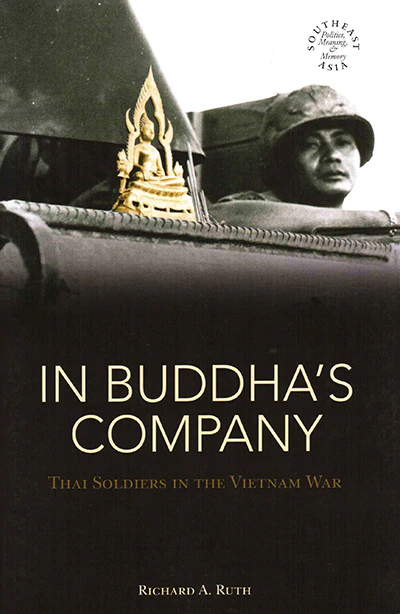

The cover of Richard A. Ruth’s book In Buddha’s Company features a Thai armored personnel carrier during the Vietnam War. It demonstrates that even Śākyamuni Buddha can go to war—or at least protect the Buddhist soldiers fighting in the war.

Buddhist sutras weaponized

But what of Buddhist sutras, could they also serve as an enabling mechanism to promote violence? One example comes from the Great Prayer Service that was solemnly held at the Sōtō Zen Monastery of Sōji-ji for seven days, beginning on 1 September 1944. The monastery explained that the purpose of its recitation as follows: “We reverently recited the sutras for the health of His Majesty, the well-being of the Imperial lands, and the surrender of the enemy countries.” (italics mine; Victoria 2006, 141)

A second example is provided by Rinzai Zen Master Yamazaki Ekijū, who instructed his disciple, Imperial Army Lt. Col. Sugimoto Gorō, as follows: “You are strong, and your unit is strong. Thus I think you will not fear a strong enemy. . . . You should recite the Heart Sutra once every day. This will ensure good fortune on the battlefield for the Imperial military.” (italics mine; Victoria 2006, 125)

To be more accurate, in the preceding examples, it is not the sutras themselves that are believed to have the power to, among other benefits, cause the surrender of enemy countries or win victory. Instead, it is believed that the merit generated by the recitation of the sutras can be directed by the reciters toward causing enemy countries to surrender. But this raises the question of whether the merit derived from sutra recitation can legitimately be directed for the victory of one’s country over another?

Karma weaponized

Chapter 28, the concluding chapter of the Lotus Sutra, states in part:

Universal Worthy, in later ages if there are those who accept, uphold, read, and recite this sutra, such persons will no longer be greedy for or attached to clothing, bedding, food and drink, or other necessities of daily life. Their wishes will not be in vain, and in this present existence they will gain the reward of good fortune. If there is anyone who disparages or makes light of them, saying, ‘You are mere idiots! It is useless to carry out these practices – in the end they will gain you nothing!’, then as punishment for his offense that person will be born eyeless in existence after existence. . . .

If anyone sees a person who accepts and upholds this sutra and tries to expose the faults or evils of that person, whether what he speaks is true or not, he will in his present existence be afflicted with white leprosy. If anyone disparages or laughs at that person, then in existence after existence he will have teeth that are missing or spaced far apart, ugly lips, a flat nose, hands and feet that are gnarled or deformed, and eyes that are squinty. His body will have a foul odor, with evil sores that run pus and blood, and he will suffer from water in the belly, shortness of breath, and other severe and malignant illnesses.

(The Lotus Sutra)

In the first instance, the understanding of karma presented in this sutra has long been used in East Asia to justify differences in social and economic status as well as the presence of physical and mental infirmities. That is to say, all of these differences are the karmic fruit of an individual’s good and evil actions in this and previous lives. Thus, those in poverty, or unable to see or hear, or who are otherwise disabled have no one to blame but themselves, for everything that happens to them is their own fault. Among other things, this has resulted in families hiding their handicapped children away from public sight or worse, in the hope that the entire family will not be regarded as tainted by the wider community.

This understanding of “karmic retribution” was also a part of all wartime Japanese Buddhist schools. For example, in 1902, prior to the Russo-Japanese War, True Pure Land (Shin) Buddhist Chaplain Satō Gan’ei asserted: “Everything depends on karma. There are those who, victorious in battle, return home strong and fit only to die soon afterwards. On the other hand, there are those who are scheduled to enter the military yet die before they do so. If it is their karmic destiny, bullets will not strike them, and they will not die. Conversely, should it be their karmic destiny, even if they are not in the military, they may still die from gunfire. Therefore there is definitely no point in worrying about this. Or expressed differently, even if you do worry about it, nothing will change.” ( Victoria 2003, 153)

Rebirth weaponized

During World War Two, Japanese Buddhist priests used the doctrine of rebirth to assuage the grief and anger of family members at the death of loved ones. The Sōtō Zen scholar-priest Yamada Reirin wrote: “The true form of the heroic spirits [of the dead] is the good karmic power that has resulted from their loyalty, bravery, and nobility of character. This cannot disappear. . . . The body and mind produced by this karmic power cannot be other than what has existed up to the present. . . . The loyal, brave, noble, and heroic spirits of those officers and men who have died shouting, ‘May the emperor live for ten thousand years!’ will be reborn right here in this country.” (italics mine; Victoria 2006, 132)

The True Pure Land (Shin) scholar-priest Ōsuga Shūdō wrote: “Reciting the name of Amitābha Buddha makes it possible to march onto the battlefield firm in the belief that death will bring rebirth in paradise. Being prepared for death, one can fight strenuously, knowing that it is a just fight, a fight employing the compassionate mind of the Buddha, the fight of a loyal subject. Truly, what could be more fortunate than knowing that, should you die, a welcome awaits in the Pure Land of Amitābha Buddha?” (Victoria 2003, 199–200)

Yamada Reirin and Ōsuga Shūdō were far from the first in Japan to weaponize the Buddhist teaching of rebirth. The famous 14th century warrior Kusunoki Masashige is regarded as the embodiment of the samurai ideal of loyalty. Although his forces were greatly outnumbered, Kusunoki remained loyal to Emperor Go-Daigo to the end. Prior to committing suicide, he said: “[I vow to be] reborn seven times over to punish the brigands [who rebelled against the emperor].” During World War Two, Kusunoki became an inspiration to kamikaze pilots and others who saw themselves as his spiritual heirs in sacrificing themselves for the emperor. For example, here is the headband of Kurokawa Fumio who piloted a miniature, kamikaze submarine on its one way journey. The headband reads: “[I pledge to be] reborn seven times to repay my debt of gratitude to my country.”

Skillful means (upāya) weaponized

The Upāya-Kauśalya Sūtra (Skillful Means Sutra) includes a story about Śākyamuni Buddha when he was still a bodhisattva. On board a ship he captained, Śākyamuni discerns there is a robber intent on killing all of the passengers and decides to kill the robber, not only for the sake of the passengers but also to save the robber from the karmic consequences of his horrendous act. The negative karma from killing the robber should have accrued to Śākyamuni, but as he explained: “Good man, because I used ingenuity out of great compassion at that time, I was able to avoid the suffering of 100,000 kalpas of samsāra [the ordinary world of form and desire] and that wicked man was reborn in heaven, a good plane of existence, after death.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, the CIA armed Tibetan guerrillas to fight the Chinese military. The Dalai Lama defended the guerillas’ actions in a filmed BBC interview as follows: “It is a basic Buddhist belief that if the motivation is good and the goal is good, then the method, even apparently of a violent kind, is permissible. But then, in our situation, in our case, whether it was practical or not, I think that is a big question.” (italics mine; YouTube)

The Dalai Lama’s reference to the importance of good motives and goals places his thought squarely in accord with the preceding sutra. Additionally, whether killing Chinese soldiers is “practical or not” reduces the question to just how “skillful” it is to do so. At least for the Dalai Lama, the precept forbidding killing is of no concern.

If these words seem incongruent with the popular image of the Dalai Lama as a man of peace, he made nearly the same assertion in his congratulatory message to the United Kingdom’s military on the occasion of its Armed Forces Day of 21 June 2010. He wrote: “I have always admired those who are prepared to act in the defense of others for their courage and determination. In fact, it may surprise you to know that I think that monks and soldiers, sailors, and airmen have more in common than at first meets the eye. . . . Naturally, there are some times when we need to take what on the surface appears to be harsh or tough action, but if our motivation is good our action is actually non-violent in nature.” (italics mine; Buddhist Military Sangha) On the one hand, the Dalai Lama’s earlier emphasis on “good goals” disappears but is replaced with the assertion that the “tough action” soldiers sometimes take is “actually non-violent in nature,” albeit if “our motivation is good.”

It is difficult not to recall the old proverb: “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

Compassion weaponized

According to the Upāya-Kauśalya Sūtra, the Buddha killed the robber “out of great compassion” for him. Similarly, the Sanskrit Mahāparinirvāna Sūtra reveals how Śākyamuni Buddha killed several high-caste Brahmins in a previous life to prevent them from slandering the Dharma. The compassion here is said to have originated out of Śākyamuni’s desire to save the Brahmins from the karmic consequences of their slander.

During World War Two, Zen-trained Lt. Col. Sugimoto Gorō wrote: “The wars of the empire are sacred wars. They are holy wars. They are the practice of great compassion.” (italics mine; Victoria 2006, 119) Two Sōtō Zen scholars added: “Were the level of wisdom of the world’s people to increase, the causes of war would disappear and war cease. However, in an age when the situation is such that it is impossible for humanity to stop wars, there is no choice but to wage compassionate wars which give life to both oneself and one’s enemy. Through a compassionate war, the warring nations are able to improve themselves, and war is able to exterminate itself.” (Victoria 2006, 91)

Bodhisattva practice weaponized

In 1937, at the time of Japan’s full-scale invasion of China, Rinzai Zen scholar-priest Hitane Jōzan wrote: “Speaking from the point of view of the ideal outcome, this is a righteous and moral war of self-sacrifice in which we will rescue China from the dangers of Communist takeover and economic slavery. We will help the Chinese live as true Orientals. It would therefore, I dare say, not be unreasonable to call this a sacred war incorporating the great practice of a bodhisattva.” (my italics; Victoria 2006, 134)

No-self weaponized

The first step in understanding how the doctrine of “no-self” (Jap: muga) can be weaponized is to recall the core Buddhist teaching of anātman. Composed of the negative prefix an (no) plus ātman, this Sanskrit term denies the existence of an eternal, unchanging self or soul. It is typically translated into English as no-self. It is a corollary of the teaching of anitya (nothing permanent). It leads to the Mahāyāna understanding of the ultimate emptiness of all things.

The 17th century Rinzai Zen Master Takuan wrote the following to his warrior patron: “The uplifted sword has no will of its own, it is all of emptiness. It is like a flash of lightning. The man who is about to be struck down is also of emptiness, and so is the one who wields the sword. None of them are possessed of a mind that has any substantiality. As each of them is of emptiness and has no mind, the striking man is not a man, the sword in his hands is not a sword, and the ‘I’ who is about to be struck down is like the splitting of the spring breeze in a flash of lightning.” (Victoria 2003, 26)

In March 1937, Ishihara Shummyō, a leading Sōtō Zen priest and spokesperson for the school said: “Zen master Takuan taught that in essence Zen and Bushidō were one. . . . I believe that if one is called upon to die, one should not be the least bit agitated. On the contrary, one should be in a realm where something called ‘oneself’ does not intrude even slightly. Such a realm is no different from that derived from the practice of Zen.” (Victoria 2006, 103)

Imperial Army Major Ōkubo Kōichi responded: “The soldier must become one with his superior. He must actually become his superior. Similarly, he must become the order he receives. That is to say, his self must disappear [italics mine]. Then he will advance when told to advance. . . . On the other hand, should he believe that he is going to die and act accordingly, he will be unable to fight well. What is necessary is that he be able to act freely and without [mental] hindrance.” (Victoria 2006, 103)

Lt. Col. Sugimoto Gorō wrote: “The reason that Zen is important for soldiers is that all Japanese, especially soldiers, must live in the spirit of the unity of sovereign and subjects, eliminating their ego and getting rid of their self. It is exactly the awakening to the nothingness (Jap: mu) of Zen that is the fundamental spirit of the unity between sovereign and subjects. Through my practice of Zen I am able to get rid of my ego. In facilitating the accomplishment of this, Zen becomes, as it is, the true spirit of the imperial military.” (italics mine; Victoria 2006, 124)

Sōtō Zen master Yasutani Haku’un explained: “In the event one wishes to exalt the Spirit of Japan, it is imperative to utilize Japanese Buddhism. The reason for this is that as far as a nutrient for cultivation of the Spirit of Japan is concerned, I believe there is absolutely nothing superior to Japanese Buddhism. . . . That is to say, all the particulars [of the Spirit of Japan] are taught by Japanese Buddhism, including the great way of ‘no-self’ that consists of the fundamental duty of ‘extinguishing the self in order to serve the public [good]’; the determination to transcend life and death in order to reverently sacrifice oneself for one’s sovereign; the belief in unlimited life as represented in the oath to die seven times over to repay [the debt of gratitude owed] one’s country; reverently assisting in the holy enterprise of bringing the eight corners of the world under one roof; and the valiant and devoted power required for the construction of the Pure Land on this Earth.” (italics mine; Victoria 2003, 70)

One of the Imperial Navy’s kamikaze pilots wrote his final piece of calligraphy as follows: “With complete loyalty I selflessly repay the debt of gratitude I owe my nation.” Needless to say, it was not only the kamikaze pilots themselves who recognized the importance of selflessness, the well-known Sōto Zen scholar-priest Masunaga Reihō had this to say: “The source of the spirit of the Special Attack Forces (aka kamikaze) lies in the denial of the individual self and the rebirth of the soul that takes upon itself the burden of history. From ancient times Zen has described this conversion of mind as the achievement of complete enlightenment.” (italics mine; Victoria 2006, 139)

In equating the selfless, suicidal spirit of the kamikaze pilots of the Special Attack Forces with complete enlightenment, Masunaga can be said to have taken Zen Buddhism to the militaristic extreme.

Samādhi power weaponized

In Buddhism, samādhi refers to the concentrated state of mind, that is, the mental “one pointedness” acquired through the practice of meditation. Prior to and during the Asia-Pacific War, Japanese Zen leaders, including D. T. Suzuki, often wrote about this meditation-derived power, emphasizing the effectiveness of samādhi-power in battle. They all agreed that the Zen practice of seated, cross-legged meditation (zazen), was the fountainhead of this power, a power as available to modern Japanese soldiers as it had been to samurai warriors in the past.

When Lt. Col. Sugimoto died on the battlefield in 1937, Rinzai Zen Master Yamazaki Ekijū wrote: “A grenade fragment hit him in the left shoulder. He seemed to have fallen down but then got up again. Although he was standing, one could not hear his commands. He was no longer able to issue commands with that husky voice of his. . . . Yet he was still standing, holding his sword in one hand as a prop. . . . In the past it was considered to be the true appearance of a Zen priest to pass away while doing zazen. Those who were completely and thoroughly enlightened, however, could die calmly in a standing position. The reason this was possible was due to samādhi power.” (italics mine; Victoria 2006, 125–26)

Samādhi power was even available to a Buddhist terrorist, Ōnuma Shō, who assassinated Japan’s former finance minister, Inoue Junnosuke, in February 1932. At his trial he stated: “After starting my practice of zazen I entered a state of samādhi the likes of which I had never experienced before. I felt my spirit become unified, really unified, and when I opened my eyes from their half-closed meditative position I noticed the smoke from the incense curling up and touching the ceiling. At this point it suddenly came to me—I would be able to carry out [the assassination] that night.” (italics mine)

Defense of the Dharma weaponized

The Sanskrit Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra admonishes followers to protect the Dharma at all costs, even if it means using weapons to do so and breaking the prohibition against taking life. Similarly, the Gaṇḍavyūha Sūtra describes an Indian king named Anala who is singled out for praise because he is said to have made killing into a divine service, in order to reform people through punishment.

In connection with Sri Lanka’s recently concluded bitter and lengthy civil war with its non-Buddhist Tamil minority, Priyath Liyanage described the situation in Sri Lanka at the time: “It must be remembered that Sri Lankan Buddhists do strongly believe they have a duty to protect and uphold their faith and that tens of thousands of Buddhist monks have taken sacred vows to do so.” (Accord)

In a 2005 sermon to Sri Lankan soldiers, Ven. Vimaladhajja included the following poem: “Dutugāmunu, the lord of men, fought a great war [against Hindu Tamils]. He killed people in order to save the [Buddhist] religion [italics mine]. He united the pure Sri Lanka and received comfort from that in the end [of samsāra]” (Jerryson and Juergensmeyer 2010, 169). Dutugāmunu was a Buddhist king in what is today Sri Lanka, who reigned from 161–137 BCE. He is renowned for having reunited the whole island by defeating and overthrowing Elara, a Hindu Tamil prince from the Indian Chola Kingdom who had invaded.

In 2012, the extreme nationalist organization Bodu Bala Sena (BBS/Buddhist Power Force) was formed in Sri Lanka. The BBS generally opposes pluralist and democratic ideologies, and criticizes non-extremist Buddhist monks for failing to take action against the rise of Western religions within Sri Lanka. On 17 February 2013, the BBS held a meeting in a suburb of Colombo attended by around 16,000 people, including 1,300 monks. At the rally, the BBS general secretary Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara stated: “This is a government created by Sinhala Buddhists, and it must remain Sinhala Buddhist. This is a Sinhala country, Sinhala government. Democratic and pluralistic values are killing the Sinhala race.” He also told the crowd at the rally that they “must become an unofficial civilian police force against Muslim extremism.” (Wikiwand)

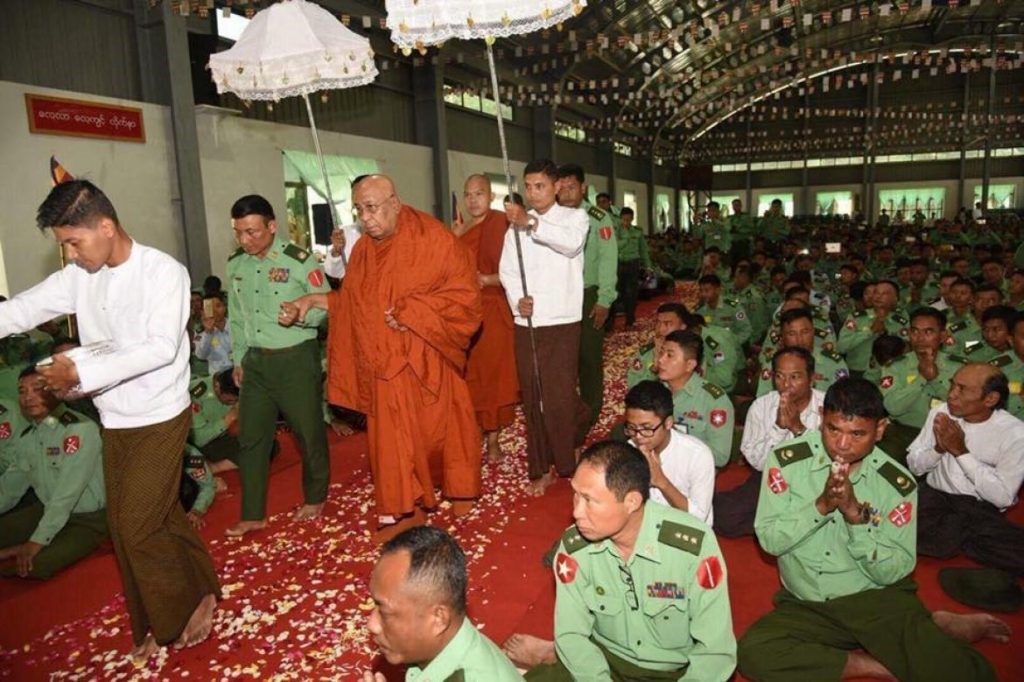

Not only Sri Lankan Buddhists use Dutugāmunu’s victory over Hindu Tamils, as recorded in the non-canonical Sinhalese Mahāvamsa (Great Chronicle), to justify killing. As recently as November 2017, Sitagu Sayadaw, a senior monk in Myanmar known for his charismatic leadership and practice of engaged Buddhism, commented on the regret Dutugāmunu is said to have felt following his victory. In a sermon Sitagu gave to the officers of the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military, he recalled that the Buddhist clerics who had accompanied Dutugāmunu into battle assured the king that he need not regret the untold numbers killed. Why? Because in reality, the king had slain only one-and-a-half human beings. One of the slain was a Buddhist who had taken the three refugees but the other, the half, had only taken the five precepts.

According to the Mahāvamsa, the remainder of the slain were unbelievers and evil men who were to be regarded as no more than beasts. On the other hand, the clerics claimed the king had brought glory to the doctrine of the Buddha in manifold ways: “Don’t worry, King, it’s only a little bit of sin. Despite that you killed millions of people, they were only one-and-a-half real human beings.” Sitagu recounted to the officers: “I’m not saying that monks from Sri Lanka said that,” adding: “Our soldiers should bear that in mind and should serve in the military, I would urge.” (Frontier Myanmar)

Mara weaponized

As for Theravāda Buddhism in Thailand, in 1976 the Thai monk Kitti Wuttho claimed: “[Killing communists is not killing persons] because whoever destroys the nation, the religion, or the monarchy, such bestial types are not complete persons. Thus we must intend not to kill people but to kill Mara [lit. Destruction]; this is the duty of all Thai.” (Anderson 1998, 167) Similar in spirit to the Mahāvamsa, identifying Thai communists with Mara meant they were no longer considered human beings and could therefore be killed with karmic immunity and without breaking the Vinaya precept forbidding killing. Identifying those outside of one’s faith as “less than,” evil, or even non-human is one of the most common violence-enabling mechanisms, found in all major religions.

Rear Admiral Sarath Weerasekara served as the Sri Lankan director general of the Civil Defence Force during the civil war with the LTTE [Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam], headed by Prabhakaran. In May 2009 Weerasekara, who holds a MA in Buddhist philosophy, explained the reasons for the Civil Defence Force’s success as follows:

I think one main reason for this success is that we fight this war as per Buddhist Philosophy. The Buddha has preached how to defeat Mara in the following stanzas and we follow exactly that:

Kumbupaman Kaya Miman Vidithwa

Nagaroopaman Chiththa Midan Tapethwa

Yodecha Maran Pagna Udena

Jithanwa Rakke Anusevanosiya“Kumbupaman Kaya Miman Vidithwa,” means that you must think of your body as a clay pot; there is no value in the body.

“Nagaroopaman Chiththa Midan Tapethwa,” you must have your mind in a fortress, you should not allow your mind to deviate; focus your attention.

“Yodecha Maran Pagna Udena” you must fight the enemy with wisdom.

“Jithanwa Rakke” you must protect what you have won and ‘Anusevanosiya’ means you must never have any interval or a ceasefire.

That is what Lord Buddha has said about defeating Mara. Today our Mara is Prabhakaran. We have fought this war with wisdom. One of the key factors for our success is that we fought it in accordance with the guidelines given by Buddha to defeat Mara.

(Business Today Online)

On the occasion of US Memorial Day in 2010, US Navy lieutenant and Buddhist chaplain Jeanette Yuinen Shin wrote: “This year’s Vesak observance, the remembrance of Lord Buddha’s Birth, Enlightenment, and Parinirvana occurs closely to our Memorial Day observance. On both occasions, this is a time for the remembrance of deeds that provided for our Emancipation from suffering. The Buddha’s final victory over Mara, and our military veterans who gave the “last full measure” so that we may have freedom today. Namo Amida Butsu.” (italics mine; Buddhist Military Sangha)

As the above examples reveal, killing sanctioned in the name of “defense of the Dharma” or “killing/defeating Mara” is today conflated with nationalism, thereby justifying the use of violence on the part of one’s nation, either internally against alleged domestic enemies or externally against foreign enemies. In the case of multi-ethnic Buddhist nations, such as Sri Lanka and Myanmar, violence undertaken against a non-Buddhist minority can also be justified as a necessary measure to defend the Dharma. Although it has been renamed, Myanmar’s MaBaTha (Association for the Protection of Race and Religion) is a case in point. It is led by monks who maintain they are defending the Bamar Buddhist majority from the country’s Rohingya and other Muslims.

MaBaTha was the successor to an earlier anti-Muslim organization known as the 969 movement. In 2017, the MaBaTha changed its name to the Buddha Dhamma Parahita Foundation. However, it is still widely referred to by its old name, MaBaTha. In addition to 969 and MaBaTha, various other monastic and lay organizations seek to protect Buddhism from the alleged dangers posed by Islam. South Asia Citizens Web offers more detailed descriptions of these organizations and Buddhist nationalism in Myanmar in general.

The Buddhadharma weaponized

Despite the preceding examples, it is hard to believe that it would be possible for any Buddhist to turn the Buddhadharma itself into a weapon. Yet it was done nevertheless by D.T. Suzuki, the world-famous Buddhist scholar primarily responsible for introducing Zen Buddhism to the West. In 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, Suzuki wrote an article in English titled “The Buddhist View of War.” It read in part:

War is abominable, and there is no denying it. But it is only a phase of the universal struggle that is going on and will go on, as long as one breath of vitality is left to an animate being. It is absurdity itself to have perpetual peace and at the same time to be enjoying the full vigor of life. We do not mean to be cruel, neither do we wish to be self-destructive. When our ideals clash, let there be no flinching, no backsliding, no undecidedness, but for ever and ever pressing onwards. In this kind of war there is nothing personal, egotistic, or individual. It is the holiest spiritual war.

One thing most detestable and un-Buddhistic in war is its personal element. Egotistic hatred for an enemy is what makes a war most deplorable. But every pious Buddhist knows that there is no such irreducible a thing as ego. Therefore, as he steadily moves onward and clears every obstacle in the way, he is doing what has been ordained by a power higher that himself; he is merely instrumental. In him there is no hatred, no anger, no ignorance, no prejudice. He has lost himself in fighting. . . .

Let us then shuffle off the mortal coil whenever it becomes necessary, and not raise a grunting voice against the fates. From our mutilated, mangled, inert corpse will there be the glorious ascension of something immaterial which leads forever progressing humanity to its final goal. Resting in this conviction, Buddhists carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying until they gain final victory.

(emphasis mine; Suzuki 1904, 179-82)

Śākyamuni Buddha weaponized

If, as D. T. Suzuki demonstrated, it was possible to weaponize the Buddhadharma, then perhaps it is not surprising that Śākyamuni Buddha himself could also be weaponized. Not surprising, that is, when the person doing the weaponizing was D. T. Suzuki’s own teacher, Rinzai Zen Master Shaku Sōen. It was Sōen who, in 1896, had certified Suzuki’s initial enlightenment experience, kenshō, as authentic. Later, reflecting on why he had become a chaplain in Manchuria during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5, Sōen wrote:

I wished to have my faith tested by going through the greatest horrors of life, but I also wished to inspire if I could our valiant soldiers with the ennobling thoughts of the Buddha, so as to enable them to die on the battlefield with the confidence that the task in which they are engaged is great and noble. I wished to convince them of the truth that this war is not a mere slaughter of their fellow beings, but that they are combating an evil, and that, at the same time, corporal annihilation really means a rebirth of [the soul], not in heaven, indeed, but here among ourselves. I did my best to impress these ideas upon the soldiers’ hearts.

(Shaku 1906, 203)

One is left to wonder which of the Buddha’s “ennobling thoughts” allowed Japanese soldiers, engaged in enlarging the Japanese Empire, “to die on the battlefield with the confidence that the task in which they are engaged is great and noble?”

Conclusion

These are only a few examples demonstrating that Buddhism has a long historical and doctrinal connection to violence, despite the non-violent teachings of its founder. In Buddhism’s case, both praxis and such doctrines as karma, rebirth, skillful means, compassion, selflessness, and samādhi power, each a core Buddhist teaching, have long been used as “violence-enabling mechanisms” to justify violence and warfare.

One would like to think that Buddhists, who believe they are able through their practice to gain insight into “things as they are,” would be willing, once they understood the nature of the problem, to dedicate themselves to the difficult task of cleansing Buddhism of these deeply entrenched violence-enabling mechanisms. However, until, and unless, Buddhists individually and collectively say “No more!” Buddhism will, like all of the world’s other major religions, continue to hold instincts for war, a religion of both peace and violence.

References

Anderson, Benedict. 1998.The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World. London: Verso.

Jerryson, Michael and Mark Juergensmeyer. 2010. Buddhist Warfare. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Liyanage, Priyath. 1998. “Popular Buddhism, Politics & the Ethnic Problem,” in Accord, No. 4, August 1998. Accessed on 19 April 2022 at: https://www.c-r.org/accord/sri-lanka/popular-buddhism-politics-and-ethnic-problem.

Shaku, Soyen and D. T. Suzuki. (trans.) 1906. Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot. Chicago: Open Court Press.

Suzuki, Daisetsu Teitarō. 1904. “The Buddhist View of War” in The Light of Dharma, July, 1904, Vol. 4. No. 2, 179-182. Accessed on 3 May 2022 at: http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/CriticalZen/A-Buddhist-View-of-War.html.

Victoria, Brian Daizen. 2020. Zen Terror in Prewar Japan: Portrait of an Assassin. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield.

Victoria, Brian Daizen. 2006. Zen at War, second ed. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield.

Victoria, Brian Daizen. 2003. Zen War Stories. London: RoutledgeCurzon Press.

Watson, Burton (trans.). 1993. The Lotus Sutra. New York: Columbia University Press. Accessed on 23 April 2022 at: http://nichiren.info/buddhism/lotussutra/text/chap28.html.

See more

Shielding the Innocent – Rear Admiral Sarath Weerasekara (Business Today Online)

Pt 1 CIA & Tibetan Buddhism – & the propaganda war against China – Opperation: “Shadow Tibet Circus” (YouTube)

The Dalai Lama’s Message to the Armed Forces (Buddhist Military Sangha)

Buddhist Military Sangha

The Mahavamsa

Tatmadaw, Sangha and government must work together, Sitagu Sayadaw says in sermon to officers (Frontier Myanmar)

Bodu Bala Sena (Wikiwand)

The Rise of MaBaTha – Extreme Buddhist Nationalism in Myanmar (South Asia Citizens Web)

Your basic approach towards studying religious violence is heavily biased and clearly flows from a warped leftist practice of equating all ‘god’ traditions or religions as being one and the same.

There are essentially two kinds of violence, whether in religious systems or ideologies like rationalism/ communism or in any other system. One is the negative kind, where an ideology attacks other groups in order to convert them or to annihilate them ….. and in case of Abrahamic religions and communism, this flows from an ideological hatred.

There is another kind of violence, which is reactive or defensive in nature — which doesn’t flow out of ideological hatred or a need to rule over others, but out of a need to protect one’s system from predatory ideologies (like left or Abrahamic religions). This is an essential and basic (also positive) human trait without which human survival is not possible.

The negative, predatory violence and defensive or reactive violence cannot be equated, nor can the two kinds of religious systems, except by bigoted minds.

Hinduism and I am sure, Buddhism too, does not teach or promote predatory violence of the kind islamists and leftists indulge in. Hinduism, e.g. preaches, that Non-violence is the greatest virtue, but in case the ‘dharma,’ or the ‘society’ is under attack, then violence against the attackers is even a greater virtue.

The pagans who did not follow these rules against Christianity, islam or liberals did not take long to perish. That is why Hinduism has survived the three.

Dear Friend,

Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts about the use and nature of violence. I am left to wonder, however, whether in light of your last comment (That is why Hinduism has survived the three), you may be describing what you believe to be the nature of Hinduism rather than Buddhism. Be that as it may, it would certainly help (or simplify) our understanding of violence if, as you claim: “There are essentially two kinds of violence,” one type of which is ‘bad’ and the other is ‘good’, i.e., one which is reactive or defensive in nature. . . . an essential and basic (also positive) human trait without which human survival is not possible.”

Unfortunately, in today’s world, wars between nations are always described to the citizens of the nations at war that their war is ‘defensive’ in nature, even the Nazis claimed this. The best example of this is the following quotation from Hermann Goering who famously said:

“Why of course the people don’t want war. Why should some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece? Naturally the common people don’t want war neither in Russia, nor in England, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy, or a fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship.

Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the peacemakers for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same in any country.”

Is this a description of the “essential and basic (also positive) human trait” you are speaking of?

As for Buddhism, in Chapter 10, verse 129 of the Dhammapada, the Buddha taught:

“All tremble at violence, all fear death. Comparing oneself with others do not harm, do not kill.”

Would you please explain which of the two kinds of violence that you claim exist the Buddha is referring to?

I look forward to your response.

Dear Dr. Victoria – reading this webpage is an update of my reading from & about you in 2010 and around, and still the reports you bring to the open knowledge are most disturbing. One more question occurs by reading the above and my being riddled: how could this happen, that in the buddhist schools/traditions such destructive traits could be planted in – and even more: how could it happen, that seemingly no buddhist school performs analysis on “what can we do that this misaligning of the Buddha’s path shall not happen (again) in our lineage?” This second question teases me much currently and I would like to communicate about ideas around this with you preferred via email. Is this perhaps possible?