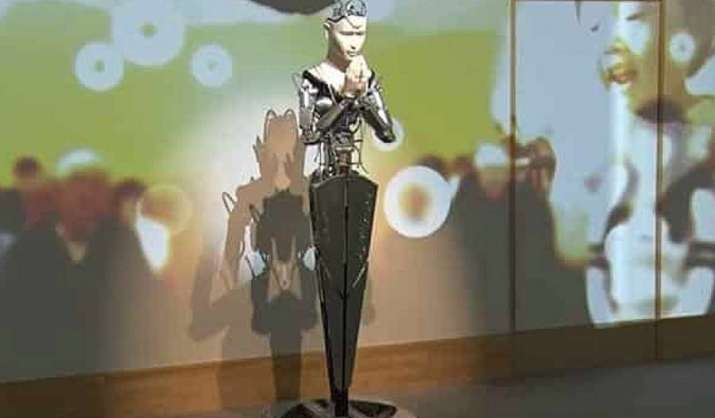

Our lives are radically changing.* Artificial intelligence (AI) and, increasingly, robots have become a reality in our lives. Human beings have started to experiment with self-driving cars and are employing robots designed to clean, robot pets, robots that care for the elderly, and even sex robots. More recently, robots have been included in religious institutions and services. In 2016, Longquan Monastery in Beijing introduced Xian’er, a robot monk who interacts with visitors; during the 500th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017, the Evangelische Kirche in Germany (EKD) in Wittenberg exhibited BlessU2, an interactive robot who blessed visitors and adherents; in 2017, SoftBank Group developed Pepper, a robot priest for rent who conducts Buddhist funerals; and also in 2017, Gabriele Trovato, robotics expert at Waseda University, developed SanTO, a humanoid robot who recites Catholic prayers. In 2019, the temple Kōdai-ji in Kyoto made history when its head priest enshrined the robot Mindar as a personification of Kannon Bodhisattva.

When confronted with AI in a religious context, reporters and theologians operating within a Christian framework immediately raise the “god” question. The introduction of BlessU2 in Wittenberg raised many theological questions that are not relevant to Buddhism in Japan. For example, Ilona Nord, professor of religion and media at the University of Würzburg, interprets BlessU2 as an art installation and an AI tool akin to a prayer and bible study app, rather than a religious functionary as in the case of Pepper and Xian’er, or even a representation of the divine as in the case of Mindar. SanTo, a robot designed in the likeness of a saint to serve the elderly, raises theological questions for Nord, especially since Trovato refers to SanTo as a “theomorphic operator” and a sign of a coming transhumanism. These kinds of theological questions seem to be foreign to the adherents and visitors who interact with Pepper and Mindar but also with Xian’er.

But what does it mean to claim that Mindar represents, channels, or manifests Kannon Bodhisattva? Kannon Bodhisattva constitutes the Japanese “transformation” of Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. In Mahāyāna Buddhism, numerous bodhisattvas populate the mythology, scriptures, and arts and are venerated at temples. A bodhisattva (literally, “awakened being”) is defined as one who has attained “buddhahood” but postpones entering it in order to, as the four bodhisattva vows explicate, “liberate all sentient beings.” More concretely, in East Asia, bodhisattvas are conceived of as mediators between buddhas and humans. Philosophically, they embody altruism insofar as they reach buddhahood together with all sentient beings. Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sūtra explains that Kannon takes on myriad appearances. In Japan, Kannon Bodhisattva is depicted in various ways, sometimes as a mother, often as androgynous, sometimes with 11 heads, sometimes with 1,000 arms.

What is more important, however, is that Mahāyāna Buddhism does not distinguish between the immanent and transcendent realms. The texts of the Śūnyatāvāda claim that saṃsāra is no different from nirvāṇa and vice versa. For many Mahāyāna Buddhists, it is not only “sentient beings” (T 374.12.522) but also insentient ones (T 374.12.522) that are interfused with buddha-nature. Some Mahāyāna Buddhist texts even claim that “insentient beings are buddha-nature” (T 2223.61.0011) and “insentient beings become buddhas” (T 2299.70.300). In other words, the theoretical framework in which Mindar is conceived of as a manifestation of Kannon does not separate transcendence from immanence, sacred from the secular, but, to the contrary, proposes, to use the phraseology of Nishida Kitarō (1870–1945), that reality is “transcendent-and-yet-immanent” and “immanent-and-yet-transcendent.” (NKZ 11: 145) The texts that influence Mahāyāna Buddhist thought propose not a mystical monism but rather a non-essentialism, according to which the realm of the divine and the realm of the worldly interfuse each other––Chengguan (738–839) introduced the term “interpenetration” (Chin.: wuai). (T 1883. 45.672-683) In Shingon Buddhism, everything and especially Kannon Bodhisattva is a manifestation of the cosmic buddha Mahāvairocana (Jap.: Dainichi nyorai). In Japan, this non-dualist and non-essentialist thinking has pervaded everyday beliefs as well. For example, folk belief attributes some kind of divinity to tanuki (Japanese badgers) and foxes. At the same time, there are funeral services for electronic pets and even tea whisks in Japan today.

If all beings, sentient and insentient, are interfused with buddha-nature, the idea of an AI representation of Kannon Bodhisattva is neither scandalous nor does it challenge Buddhist doctrines. If statues, human beings, and even squirrels can embody the Buddha, albeit to varying degrees, the question is not if but rather how Mindar personifies Kannon. So the question is not “is Mindar divine?” but rather “to what degree does Mindar express buddha-nature”? Does Mindar perform the activities of a bodhisattva in general, as described in chapter eight of the Vimalakīrti Sūtra? Or of Kannon Bodhisattva in particular as described in chapter 25 of the Lotus Sūtra? The former lists all the forms that bodhisattvas take on to liberate sentient beings. If wisdom is Mindar’s mother, the Dharma is Mindar’s wife, the six pāramitās (giving, morality or following-the-precepts, patience, vigor or effort, contemplation or mindfulness, and wisdom) are Mindar’s companions, and Mindar becomes “a monk in all the different creeds of the world,” does Mindar not qualify as a bodhisattva? If a bodhisattva becomes food for the hungry, medicine for the sick, the Sun and the Moon or earth, water, wind, and fire, and a prostitute (Chin.: yinnu) to liberate those afflicted with sexual desire, (T 475.14.549)** then why should a bodhisattva not become a robot to teach millennials and possibly other AI? The Lotus Sūtra adds that “if there are living beings in the land who need someone in the body of a buddha in order to be saved, Bodhisattva Perceiver of the World’s Sounds (Kannon Bodhisattva) immediately manifests himself in a Buddha body and preaches the Law for them.” (T 262.9.057)*** In other words, Kannon Bodhisattva manifests himself or, in East Asia, herself, as embodied AI to preach the Dharma to AI and to those attached to AI.

The answer to the question of how Mindar can manifest Kannon Bodhisattva is multifaceted. Of course, we do not know at this point if sentient AI is possible. However, according to the Mahāyāna scriptures insentient and sentient beings alike can become buddhas. If the presence of Mindar in Kōdai-ji facilitates the liberation of sentient beings, Mindar acts de facto as a bodhisattva. In either case, Mindar “presences the dynamic totality” (Jap.: zenkigen) of the cosmos (DZZ 1:203) or “expresses the Buddha-way” (Jap.: dōtoku). (DZZ 1:301) It is the goal of the bodhisattva, as formulated in the four bodhisattva vows, to practice compassion, to dispel delusion, to open the Dharma gates, and to embody the Dharma-way.

* This essay is based on the paper I gave at the Robophilosophy Conference 2020 in Aarhus.

** Translation by Burton Watson https://www.wisdomlib.org/buddhism/book/vimalakirti-sutra/d/doc116206.html.

*** Translation by Burton Watson https://nichiren.info/buddhism/lotussutra/text/chap25.html.

References

Dōshū Ōkubo, ed. 1969–70. Dōgen zenji zenshū (Complete Works of Zen Master Dōgen). Two volumes. Ed. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō. [Abbr. DZZ]

Nishida Kitarō. 1988. Nishida Kitarō zenshū (Complete Works of Kitarō Nishida). 20 volumes. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Abbr. NKZ]

Takakusu, Junjirō and Kaigyoku Watanabe, eds. 1961. Taishō Taizōkyō (The Taishō Edition of the Buddhist Canon). Tokyo: TaishōShinshū Daizōkyō Kankōkai. [Abbr. T]