One of the more interesting conundrums in religious studies is that quite a few members of the counter-culture movement in the US, commonly known as “hippies,” traveled to Japan in the 1960s to study Zen Buddhism at Rinzai and Sōtō monasteries. Actually, a friend of mine went to Japan the first time shortly after he had hitchhiked across parts of the US to attend the Woodstock music festival. What is interesting and confounding about this phenomenon is that many members of this movement were fiercely anti-authoritarian and anti-hierarchical, while most Zen monasteries in Japan are, mildly put, the opposite. Social life at the monasteries is strictly organized by the principle of seniority; life in the monastery is regulated by monastic rules interpreted and applied by the head monk, who represents the abbot. The 1989 Japanese comedy Fanshī dansu, Japanese for “fancy dance,” portrays the strictness of monastic life, albeit in a comedic and at times exaggerated fashion.

There are many possible explanations for the hierarchical structures of Zen monasteries and, to be fair, practitioners are free to leave at any time, if they choose. But what I am interested in here is the relationship between master (Jap: rōshi) and disciple, which is crucial in the Zen Buddhist tradition. This relationship is evoked and glorified in the Zen literary canon, which cites encounters between the legendary Zen masters of the Tang dynasty and their disciples, and in the Zen rhetoric after the institutionalization of Zen Buddhism during Song China. The so-called “flower sermon” in which Shakyamuni Buddha is said to have communicated his Dharma to his disciple Mahākāśyapa by holding up a flower; the “four principles of Zen” attributed to the first Chinese patriarch of Zen Buddhism, Bodhidharma, emphasize “a special transmission outside of the teachings” (Jap: kyōgebetsuden); in his Shōbōgenzō bendōwa, Dōgen echoes these ideas when he admonishes the reader to find a “true teacher” (Jap: shōshi).

This emphasis on the teacher–student relationship is not unique, but is definitely a fundamental feature of Zen Buddhism. It pervades the common Zen rhetoric as well as the ritual structures of many Zen schools. Zen monasteries and Zen centers identify their teacher as well as the teacher’s lineage. During lay ordination in Sōtō Zen, which is called “assembly to receive the precepts” (Jap: jukaie), the candidate receives a “genealogy chart” (Jap: kechimyaku), which traces the unbroken lineage from Shakyamuni Buddha to the candidate, teacher by teacher, generation by generation. This chart constitutes the institutional and ritual enactment of the this “special transmission outside of the teaching.” This is quite interesting as Dōgen proposed that the practice of “sitting only” (Jap: shikantaza) constitutes Shakyamuni’s teaching. Of course, one can argue, as many Zen practitioners do, that this chart comprises merely the symbol of shikantaza. De facto, however, it constitutes the sine qua non of practicing in the Zen Buddhist tradition.

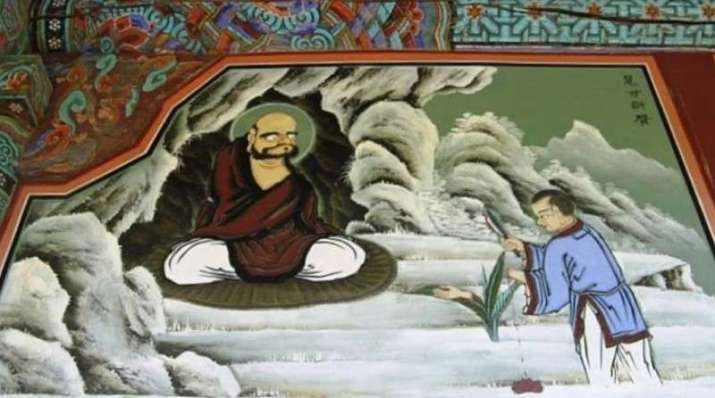

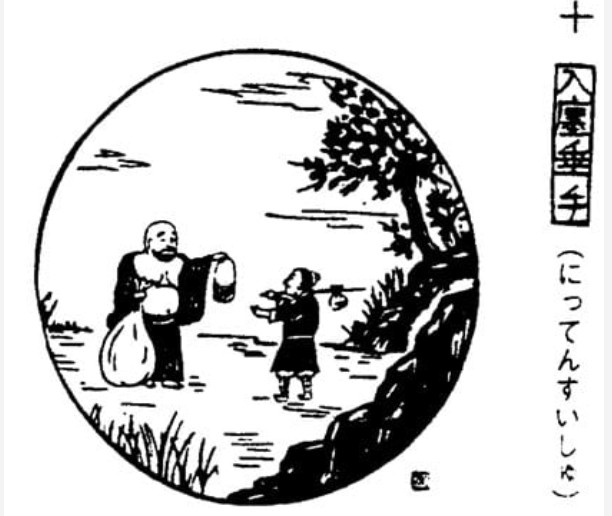

From ordinaryzensangha.org

This emphasis on the teacher-disciple relationship is neither coincidental nor philosophically or doctrinally irrelevant. It is a pervasive feature of Zen Buddhist meditation manuals. For example, Kuoan Shiyuan’s (c. 12th century) Ten Ox Pictures end with the practitioner becoming a teacher and recruiting a disciple, as if to say that the practitioner’s journey is not complete until they find themselves in a relationship with a disciple. One could say that this conclusion is a sign of good marketing and simply follows the logic of institutionalization: every member recruits a new member. But the theme of the student-disciple relationship is very consistent with the prevailing philosophy implicit in Zen Buddhist meditation manuals. As I mentioned in an earlier essay for Buddhistdoor Global, picture No.10 of Kuoan’s Ten Ox Pictures expresses the Mahāyāna Buddhist doctrine of compassion (Skt: karuna) as the highest goal and the bodhisattva ideal. But in his famous Mountain and Water Sūtra (Jap: Sansuikyō), Dōgen provides a philosophical interpretation of the teacher-student relationship:

In ancient times, Decheng left Yaoshan abruptly, lived at the river, and obtained the sage of the Huating River. Isn’t this catching a fish? Isn’t this catching a person? Isn’t this catching water? Isn’t this catching the self? That a person sees Decheng is to become Decheng. That Decheng encounters a person is to get to meet this person. (DZZ 1: 266)

While the 10th picture of Kuoan’s Ten Ox Pictures identifies compassion as the goal of meditative practice, the Buddha-way, Dōgen interprets the interaction between teacher and disciple as the necessary and sufficient condition of the “mind of awakening” (Skt: bochicitta). He believes that buddhas “express buddhahood” (Jap: dōtoku) in the encounter of “all buddhas and all ancestors.” In some sense, this idea reflects the notion that bodhisattvas enter buddhahood after or, at least, while “liberating all sentient beings.” But what Dōgen seems to say here is pretty radical. He claims that intersubjectivity is constitutive of self-consciousness or, at least, that the relationship among buddhas is constitutive of buddhahood. “To forget the self,” as he says elsewhere, then means to realize that we exist in-relationship. Of course, the above-cited passage describes the moment of attaining the “mind of awakening” or buddhahood, but it also sheds new light on his interpretation of the concept of “no-self” (Skt: anātman, Jap: muga): we are not isolated individuals, we are existentially related to others.

At the end of this essay, I would like to introduce another quote by Dōgen. This quote is from the fascicle Shōbōgenzō kattō. In this fascicle, Dōgen interprets a famous Zen story from the Entire Records of the Buddhas and the Ancestors (Chi: Fozutongji), in which Bodhidharma asks his four disciples to express what they have attained. According to this text, Bodhidharma comments on the four answers by saying, “You have attained my skin,” “my flesh,” “my bones,” and “my marrow,” respectively. (T 2035.49.291) Traditionally, these comments have been interpreted to indicate varying levels of understanding. But Dōgen disagrees. He answers:

You should know that there is you-attaining-me, me-attaining-you, attaining-me-you-are, attaining-you-I-am. . . . If you were to say that inside and outside are not one, you are not in the land where buddhas and ancestors are presenced. (DZZ 1: 333)

Our existences are intertwined like vines. The title of this fascicle, Kattō, literally “intertwining vines” already evokes this image. This is why there is no independent self. This is why bodhisattvas devote themselves to “liberating all sentient beings.” This is why buddhahood is expressed in reciprocity and compassion.

References

Dōshū Ōkubo, ed. 1969–70. Dōgen zenji zenshū (Complete Works of Zen Master Dōgen). Two volumes. Ed. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō. [Abbr. DZZ]

Takakusu, Junjirō and Kaigyoku Watanabe, eds. 1961. Taishō Taizōkyō (The Taishō Edition of the Buddhist Canon). Tokyo: TaishōShinshū Daizōkyō Kankōkai. [Abbr. T]