As we have read in earlier articles for this column, the development of the Japanese Myōō was relatively linear: from India as Saivic manifestations to the Himalayan regions as inclusions in Tantric practice, through China as Buddhist deific mainstays, and into Japan as the forms we can see today in temples and museums across the archipelago. Their vehicles were the scriptures and mandalas of the esoteric teachings that would become Japanese Shingon and Tendai mikkyō.

Perhaps the most enduring and representative symbol of the esoteric schools, also called Vajrayana, is that of the vajra (Jpn: kongō). The word can be interpreted from Sanskrit to mean any of a selection of materials synonymous with indestructibility and permanence: adamantine, diamond, or the thunderbolt. The vajra has numerous stories connected to it, most famously as a weapon commissioned by the Vedic deity Indra to help him destroy the asuras and as the tool by which the Tantric master Padmasambhava conquered and persuaded the deities of Tibet to adopt the Buddhist teachings. It is no surprise, then, that entire classes of deity incorporated the ineradicable imagery of the vajra to accurately convey their strength.

Kongō-yasha Myōō, though part of the godai myōō, did not become the object of an independent cult and is therefore a lesser known deity among the popular grouping. In the Tendai tradition, Kongō-yasha Myōō is supplanted by Ususama Myōō; in Shingon a clear distinction is made between the two. Nonetheless, he is recognized by the physical features that identify a wisdom king: the multiple faces, the flame-like hair, the aggressive stance, and the warlike implements held in many arms. Scriptures describe Kongō-yasha specifically as having three faces: two side faces with three eyes each and the central face with an unprecedented five. His front hands hold a five-pronged vajra and bell with vajra handle (Skt: vajra-ghanta) at his chest, while the others hold a bow, arrow, chakra, and sword. As the wrathful form of the celestial buddha Amoghasiddhi (Jpn: Fukuujōju nyorai), Kongō-yasha is responsible for the protection of the northern quarter and is called upon in a rite designed to subdue demons and command respect.

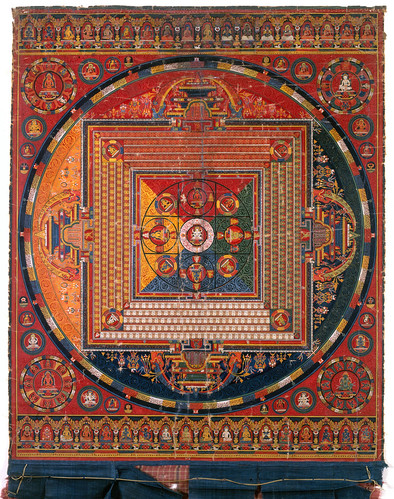

The ancient Indian unarmed martial art of Vajramukti, meaning “thunderbolt-clasped hands,” bases many of its martial poses on the mudras described in sutras. A major source of these is the Vajrasekharasutra (Jpn: Kongōchōkyō; Diamond Peak Sutra), written in the seventh century and translated by Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra in the eighth century, from which the Vajradhatu mandala (Jpn: Kongōkai mandara) is derived. Early versions of the Vajradhatu mandala show the mahabodhisattva Vajrayaksa seated in attendance to Amoghasiddhi, along with three other mahabodhisattvas, with clenched fists held before his chest—a violent posture representing the fierce aspect of wisdom employed when one is resistant to the Buddha’s teachings. It is also by this fearsome wisdom that all threats to the Buddha are destroyed; it can be assumed that demonic forces are included among these threats.

In the seventh chapter of the Chinese Renwang Jing (Jpn: Ninnōgyō; Sutra of the Humane Kings), first translated by Kumarajiva in the fourth century and then by Amoghavajra in the eighth century, prototypes of the godai myōō grouping appear as the Five Great Power Bodhisattvas (Jpn: godairiki bosatsu) and were given by Amoghavajra the names Vajrapani (Jpn: Kongōshu), Vajraratna (Jpn: Kongōhō), Vajratiksna (Jpn: Kongōri), Vajraparamita (Jpn: Kongōharamitsu), and Vajrayaksa (Jpn: Kongōyakusha). They are also known as kubosatsu (Roaring Bosatsu or “Howls”), which refers to their ability to destroy hellish beings. Already in this earliest iteration of the myōō grouping, Vajrayaksa is associated with the northern direction.

Per the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Buswell and Lopez, Jr. transliterate the Sanskrit name Vajrabhairava—a deity associated with Yamantaka (Jpn: Daiitoku myōō)—to mean “indestructibly frightening.” Likewise, Vajrapani is interpreted as “Vajra Holder.” Both capture the essence of immutability inherent to the vajra. Vajrayaksa, then, may be interpreted to mean “indestructible yaksa,” the second half referring to a class of nature spirits who would eventually serve the deva Vaisravana (Jpn: Bishamonten), guardian king of the north and himself a yaksa lord, and the medicine buddha Bhaisajyaguru (Jpn: Yakushi nyorai). The yaksas, especially in Japan as yasha, took on brutish, fearsome, almost demonic forms; yet were incorporated into folk religion and, as with the Inari and Izuna cults, became objects of popular worship.

The little information that exists on this nonetheless powerful deity necessitates some speculation on the rationale for including him in the godai myōō. What follows is merely my understanding of Kongō-Yasha’s iconographical provenance and I urge those with additional information to comment below so that we can assemble a more complete understanding of the “Destroyer of Demons.”

Kongō-Yasha myōō likely has origins as the mahabodhisattva Vajrayaksa in attendance to Amoghasiddhi, the ruling buddha of the northern quarter in the Vajradhatu mandala. This form appears gentle and compassionate; the aggression is displayed in the mudra only. Vajrayaksa in particular was employed as the prevailing wisdom against stubborn and infernal beings who threatened those on the Buddhist path. This war-like aspect was reinterpreted in Amoghavajra’s translation of the Chinese Renwang Jing as the Great Power Bodhisattva Vajrayaksa, and was given a more wrathful form to match his brutish name and violent role as a destroyer of hellish beings. As the other Howls were transformed to assume the identities of Fudō, Gōzanze, Daiitoku, and Gundari, and their respective roles, Vajrayaksa largely retained already well-established persona as a demon destroyer. Instead, his appearance was slightly altered and he took on the Japanese moniker by which he is known today. He is now counted among the five deities petitioned during a ninnō-e rite at Daigo-ji during the Heian period (794–1185) and his likeness can be seen among the beautiful myō sculptures at Tō-ji in Kyoto.

References

Buswell Jr., Robert E. and Donald S. Lopez Jr. 2013. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press: Princeton.