In this three-part series, we explore the Buddhist presence in pop culture media. We first reviewed Toei Animation’s Buddha 2. In this second entry, we interview Gaetano Maida of Buddhist Film Foundation about Buddhist-themed film-making, before moving on to analyze how the Buddha is depicted in graphic novels and manga in our third feature.

In 1925, a silent production called Prem Sanyas, or Die Leuchte Asiens, made history as the earliest Buddhist-themed film. Co-directed by Indian film pioneer Himansu Rai, who also provided the funding and actors, and German collaborator Franz Osten, who took care of the cameras and technical crews, it was adapted from Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia (1879), a long poem about the Buddha that was published as a book. There were few Buddhist-themed films made immediately afterwards due to the many wars that would devastate Asia. As they ended, national traditions of Buddhist film-making were able to germinate in South Korea, China and Hong Kong, Japan, and Thailand. Western film-makers focusing on dramatic storytelling came relatively late in the 1970s, but since then interest in shooting and watching films about Buddhist regions, traditions, and cultures has grown unabated.

Buddhist Film Foundation (BFF) screens the films springing from these national traditions around the world in a branded film festival, the International Buddhist Film Festival (IBFF). With the Berkeley, California-based BFF reaching its 15th year in 2015, executive director Gaetano Maida is busier than ever. “Buddhist Film Foundation’s broad goal is to support cinema that examines, celebrates, criticizes, and contextualizes the Buddhist insights about suffering, interdependence, impermanence—you know, the basic marks of Buddhism,” he told me. “BFF initiated the IBFF and offers a distribution service, Festival Media. We’re developing the Buddhist Film Archive [BFA] with UC Berkeley’s Center for Buddhist Studies and maintain a fiscal sponsorship program for film production funding. Also, BFF is about to launch Buddhist Film Channel [BFC.com], a video-on-demand streaming platform.”

Maida noted that BFC.com is being developed to provide a sustainable online platform for BFF’s ongoing work. He knows that the market for cultural and artistic films, particularly Buddhist ones, is a difficult one. Buddhist films need to cater to as wide an audience as possible while paradoxically keeping the content relevant to Buddhist ideas, the latter of which is a specialist trade. New technology has made things more complex: “It’s clear to us now that the film festival world must evolve along with the film industry and determine how best to integrate digital technology into a revised model that continues serving our key constituencies: film-makers, audiences, educators, and funders,” he continued.

“We have presented our festivals in eight countries on three continents so far, and it’s a little surprising to us that the most avid audiences have been in Mexico City, Singapore, Hong Kong, Vancouver, and London,” said Maida. “This programming is decidedly marginal or niche in the US, though American audiences, while modest in size, are enthusiastic in their responses. Perhaps this enthusiasm is due to some extent to the fact that we have assiduously avoided utilizing celebrity identification in connection with our programming and events.”

Maida’s passion for managing BFF is drawn from a lifetime of personal and professional investment in film-making. He grew up in New York City, immersed in the “golden age” cinema of the 1960s. He has a long list of favorite directors from that generation: Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Yasujiro Ozu, Satyajit Ray, Akira Kurosawa, Michelangelo Antonioni, Andrei Tarkovsky, François Truffaut, and Jean-Luc Godard. “Heady times!” reminisces Maida fondly. “There was also the nascent cinéma vérité [observational documentaries] movement with Richard Leacock, Donn Alan Pennebaker, and the Maysles brothers. A classmate owned a wind-up Bolex 16-millimeter camera and a projector and had money for film stock and processing! In our free time, we’d shoot three-minute shorts on color reversal film, edit it, and screen the film with music from a record player for the soundtrack.”

He got his first taste of distributing films when he borrowed his friend’s camera to volunteer for New York Newsreel, a documentary film-maker collective that produced newsreels about the anti-Vietnam War movement, civil rights protests, and labor union activities. Primarily focusing on photojournalism after he left school, Maida met Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh in the 1980s and spent some time photographing him for the magazine East/West Journal. “I casually told his organizers that Thay [Thich Nhat Hanh] would make a good subject for a film they should produce. While I was in the middle of photographing stories about homeless people living rough in Manhattan, the folks working with Thay called to ask if I wanted to make the film about him. No one else had come forward and I got a letter of exclusivity! I found myself producing and directing what became the movie Peace Is Every Step,” said Maida.

Over the next few years, Maida could see that there was no room for the selection process at film festivals to choose an entry like Peace Is Every Step, or indeed any movie that examined the spiritual aspects of contemporary life. Although he had a hand in developing what became Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, BFF was eventually founded independently in Berkeley with a few film-makers and educators in 2000. The IBFF was first held in 2003 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Thanks to its first overseas festival in Amsterdam in 2006, the IBFF was instantly recognized as one of the leading international resources for Buddhist cinema.

“We maintain an open call for entries throughout the year, so we see films almost every week. We’ve shown over 400 films and obviously commit to showing a wide spectrum of different genres. We evaluate several hundred new movies a year from all over the world. Selections for the IBFF come from these submissions, choices from other film festivals, and from film-makers with whom we have long-standing relationships,” noted Maida. “We don’t start with a preset theme, but often discover threads that we can identify for audiences: Buddhism in the West, for example. We’re very collaborative—we always work with museums, Buddhist institutions, artistic and cinematic connections, and educators. Audiences love it too.”

There are always hard-headed practicalities. For example, Maida needs to consider the factors that determine a production’s potential popularity and reach. “Geography, tradition, and funding come immediately to mind. Many films originate in Europe or North America, which is attributable to a great extent to the funding. For whatever reason, the Theravada tradition is under-represented in this arena. Based on our experience, the Vajrayana tradition is represented by a significantly greater percentage of films than the numbers of adherents might indicate, suggesting that cinema has secured a privileged place in that tradition.”

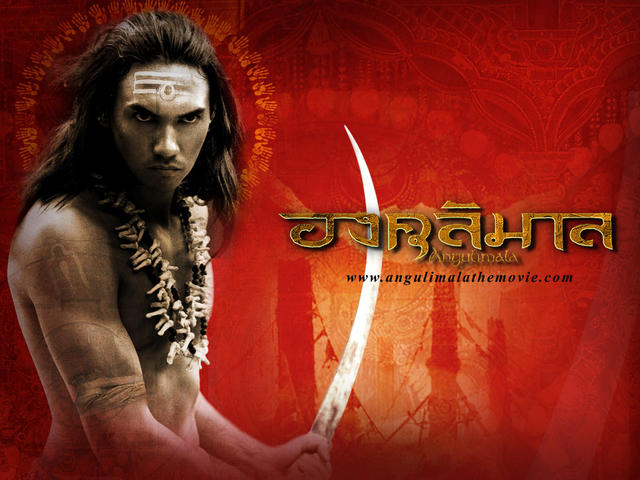

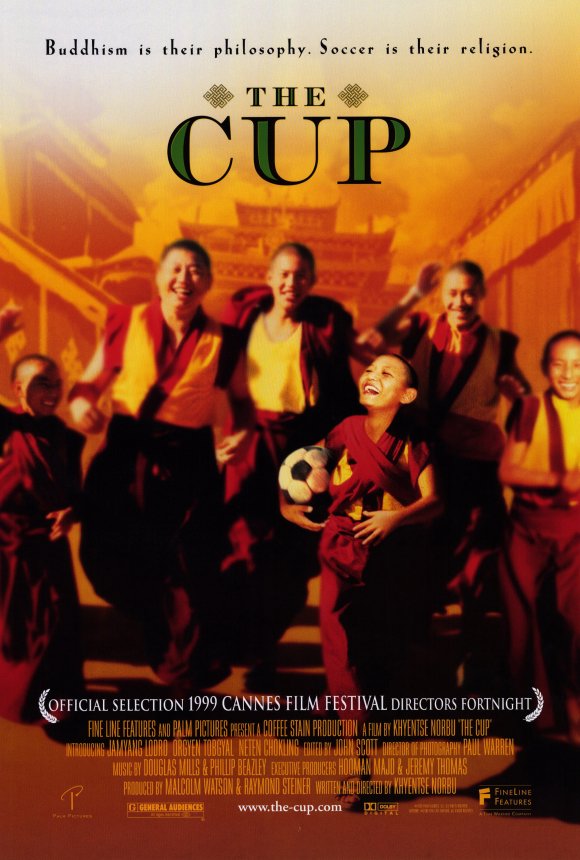

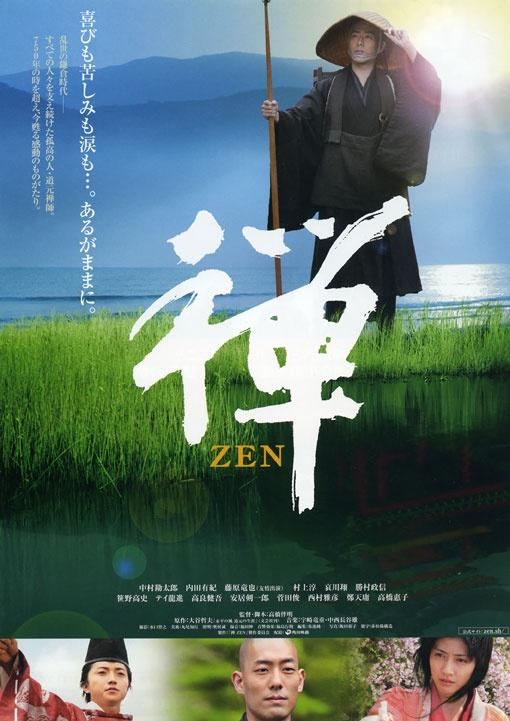

Maida’s favorite works are diverse. “There are so many I personally find compelling. Angulimala [2003] is an extraordinary Thai dramatization of the Angulimala Sutta, extremely well produced and provocative in terms of its depiction of delusion, desire, and Dharma. The Cup [1999] is a breakthrough work, written and directed by Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche. It skillfully presents the challenges of modernism within the Tibetan monastic culture, with humor and credible authenticity. Leave it to the Koreans to find a way in Hi Dharma [2001], which brings their popular gangster genre to a monastery setting with humor and energy. Zen [2009] is a Japanese historic biopic about Master Dogen. It uses his life story to help describe Buddhism and Zen in the context of a feudal society. A recent one is Golden Kingdom [2015], shot on location in Myanmar, which tells the story of young monks left on their own in a rural monastery during a time of armed conflict and encroaching change. I could go on . . .”

Looking back, Maida feels that BFF wasn’t an organic process, although he couldn’t have predicted that he would found the IBFF and carry it to success back in the days of fiddling around with his friend’s Bolex camera. “Luck and incidents or accidents were always there, but it was more a matter of identifying unmet needs and applying myself as skillfully as possible to addressing them. Sometimes it works! We never anticipated that there would be opportunities for the IBFF outside of the US. In a way, though, our work will be done when Buddhist cinema ceases to be an identifiable genre and is embraced by mainstream platforms around the world.”

See More