In this three-part series, we explore the Buddhist presence in pop culture media. We first review the second movie in the animated trilogy of Osamu Tezuka’s Buddha. In the second entry, we’ll interview Gaetano Maida of the Buddhist Film Foundation about Buddhist-themed film-making, before analyzing how the Buddha is depicted in graphic novels and manga in our third feature.

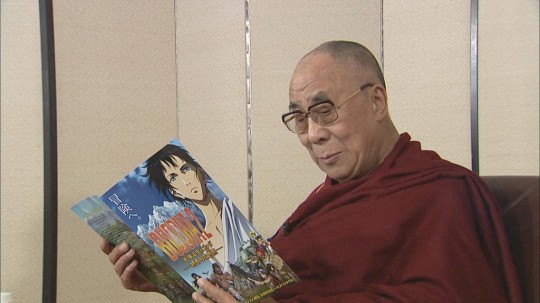

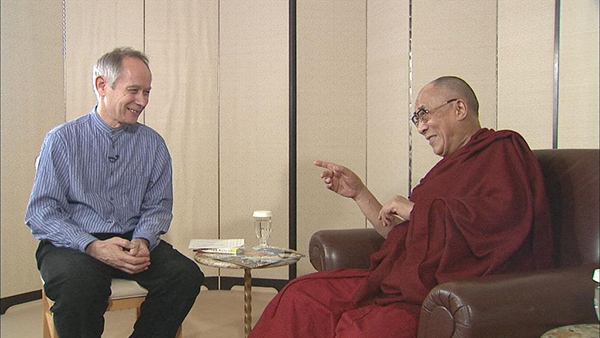

Few franchises have stimulated greater impassioned debate about how Buddhists should relate to fictional portrayals of the Buddha than Japanese artistic pioneer Osamu Tezuka’s (1928–89) 14-volume manga Buddha. Toei Animation’s Buddha trilogy, which is based on his series, has been unsurprisingly controversial. The first film, Buddha: The Beautiful Red Desert, was released in 2011 and screened in Amsterdam during the Buddhist Film Festival Europe in October that year. The second, Buddha 2: The Endless Journey, was released in 2014. The Dalai Lama was treated to a private screening of Buddha 2 and even appeared on Tokyo MX TV on 18 January 2014 to discuss it. From what he said, he seems to have liked it. “I am very thankful to have the world of the Buddha be spread by the film,” he declared.

The Dalai Lama was not the only one who lent his celebrity glitter. Toei invited the queen of Japanese pop, Ayumi Hamasaki, to sing the movie’s theme song. It also assembled a first-class cast to voice the characters, including Kiyokazu Kanze (the 26th grandmaster of the Kanze School of Noh) and Norwegian Wood’s Kenichi Matsuyama. Despite all this star power, Buddha 2 still received a lukewarm response. So far, reader reviews are aggregated at an overall 3.28 out of 5 on Yahoo! Japan, while other Japanese websites like Coco, Eiga, and Kagehinata rate it at 67 per cent, 3.0/5.0, and 7/10, respectively. Most of the Japanese complaints noted how Toei’s adaptation was curiously joyless compared to Tezuka’s bawdy, irreverent original. There is one final film to be released, and while I don’t expect its overall reception to greatly improve, I’m confident that the Dalai Lama will nevertheless enjoy it.

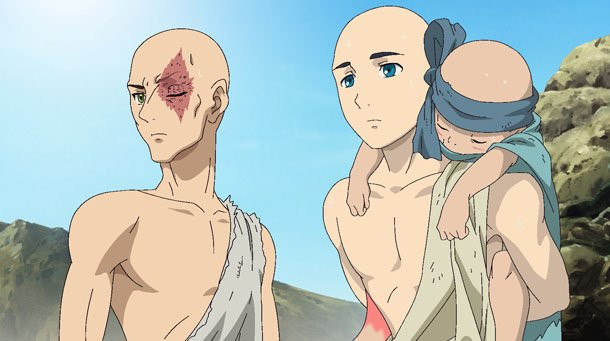

The Endless Journey is set years after The Beautiful Red Desert’s bloody conclusion. In The Beautiful Red Desert, Prince Siddhartha’s forbidden sweetheart, the bandit Migaila, had her eyes gouged out by order of his father, Suddhodhana. Buddha 2 charts Siddhartha’s journey from extreme asceticism to enlightenment with a new slew of canonical and original characters. The film isn’t perfect—in fact, it’s deeply flawed. Siddhartha’s enlightenment is presented more like a footnote when it should have been the breathtaking climax. Worse yet, some canonical characters that could have appeared awe-inspiring if reinterpreted on the silver screen, like the demon Mara, don’t even appear in the movie.

Yet if Buddha 2 suffers from a profound lack of creativity with canonical Buddhist figures, it delivers on the characters of Tezuka’s fertile imagination. Siddhartha’s reunion with the sightless Migaila is raw. In shock at meeting him again, she recalls how she begged him to become a great king after she was blinded and exiled. The disappointment in her choked voice when he almost reluctantly confesses his renunciation is portrayed to perfection by voice actress megastar, Nana Mizuki. Siddhartha and Migaila share several intimate, emotionally charged scenes (especially one in which she falls ill) where conflicted passions like lingering attachment, platonic intimacy, regret, and mutual empathy meet.

Japanese viewers were merely ambivalent over how far the film deviated from Tezuka’s comic. However, critics in Southeast Asia aimed their anger at how both the films and comics deviated from the Buddhist canon altogether. The colorful critiques, which seem to come from several Buddhist websites such as The Daily Enlightenment, charge that the creative liberties taken by Buddha 2 commit unforgivable distortions of the Buddha’s biography:

“We cannot imagine the amount of harm and possibly hellish [my emphasis] negative karma created from . . . interrupting . . . sentient beings’ otherwise progressive Buddhist spiritual life.” Also: “Movies like the above mentioned [Buddha 2] slander the Buddha and his teachings. I’m surprised it was showed on [sic] a Buddhist film fest. If the organizer has no capable person to differentiate right dharma from the wrong, perhaps they shouldn’t use the label—‘Buddhist’ on their event.” The gist should be clear: “To further horror, the festival did receive funding from some major Buddhist organisations. What an utter waste of money from the Buddhist community it is then, in selecting this film” (the film festival being castigated was the Thus I Have Seen festival, held in Singapore from 20–27 September 2014).

Writing on The Daily Enlightenment website, reviewer Ng Xin Zhao petitioned Buddhists to choose cartoons that are more “faithful” to the canon, such as Thai professor Krismant Whattananarong’s The Life of Buddha (2007). Whattananarong understood the importance of attractive visuals and commissioned Thai artists previously employed by Disney, while recruiting Buddhist writers and editors to maintain scriptural fidelity. Sadly, an English version of the film is rather difficult to find or buy, and to my amusement, when I tried to visit The Life of Buddha’s website, it had been replaced by a Japanese search engine site.

The Daily Enlightenment is correct to argue that Buddhist film festivals need to carefully evaluate the movies they screen. It is also vital to differentiate the canonical from the illegitimate within the genre of the Buddhist canon. However, I think Buddha 2 belongs in a different genre of media in the same way that Noah (2014) belongs in the genre of Hollywood blockbusters and not those of Jewish or Christian texts. Also notable for taking significant creative liberties, Noah was Hollywood’s most recent move to cash in on religious figures, but no commentator seriously thought Russell Crowe was presuming to impart serious teachings about the Flood.

On our more conservative days, we may decry the “anything goes” attitude with which large studios and conglomerates produce films about religious figures. Perhaps more thought should be given by these companies to consulting religious authorities. Nevertheless, it strikes me as rather insecure to assume that Buddhists would be so easily and fatally misled by a cartoon when many secular films have reinterpreted (and will continue to reinterpret) religious themes without being taken too seriously.

There is one advantage that Buddha 2 (and other non-religious stories about religious figures) enjoys. It is how the shadowy Siddhartha Gautama, a mysterious, distant man whom honest historians confess to knowing almost nothing about, is free to express grief, distress, and pain. These are emotions that the Buddhist canon avoids in order to present him as a perfect bodhisattva. We’ll never glimpse the vulnerabilities the historical Siddhartha suffered, but those exhibited by Tezuka’s reinterpretation imbue him with a warm, relatable quality in line with what audiences in 2015 expect of adventurous storytelling and invested character development. Many argue rightly that this creative license, for all its faults, is the prerogative of honest fiction. As long as it’s not marketed as a work of canonical inspiration, Buddha 2 provides a rare pleasure worth enjoying.

For more information, see:

Special program broadcast with the Dalai Lama (Japanese only) (otakei.otakuma.net)

Dalai Lama to Give Stamp of Approval for Buddha 2 Anime on TV (Anime News Network)

Dharma Screenings: Buddhist Film and Pop Culture—Buddhist Traditions on the Silver Screen