Imagine sitting on the floor among some of the most educated khenpos—holders of doctoral degrees in divinity—of the Karma Kagyu lineage. It’s 2010 in Dharamsala, India, and you are the only woman in the room. These Tibetan scholars have dedicated their lives to studying the Dharma, and now they are gathered because an important occasion is approaching: the 900th anniversary of the founding of the lineage. Sitting in a swivel chair facing you and the khenpos is His Holiness the 17th Gyalwang Karmapa, the young Tibetan leader of the lineage. He has just announced that a book will be published to commemorate the anniversary. This is a juicy assignment, and the scholars are excited. Swiveling in his chair, His Holiness extends a hand to you. “She’s already writing it,” he says, to the surprise of the men around you. “She’s almost done.”

That woman was Diana Finnegan, also known as Venerable Lhundup Damchö, an American nun, scholar, and translator in the Karma Kagyu lineage. Her commemorative book, Karmapa 1110-2010 (Sidhbari 2010), marked the beginning of a working relationship with His Holiness the Karmapa that continues to this day. She has since worked on a number of book projects for the lineage, including a forthcoming biography of the 16th Karmapa. Empowered by His Holiness to take a public role as a female scholar, she has also taken the initiative to build a cross-cultural community of Western nuns who live and practice together. When not in India, Ven. Damchö spends much of her time in Latin America, where she teaches the Dharma in Spanish, works with small sanghas in Mexico and Puerto Rico, and hopes to establish a nunnery in Mexico in the near future.

“I cannot begin to express how fortunate I am,” she tells me in a Skype interview from Puerto Rico. Working with His Holiness, she often reads back chapters she has written to him out loud, and they discuss weighty ideas down to the subtleties of word use. When His Holiness sprinkles his sentences with English terms, it is Ven. Damchö’s job to discern whether those terms are an approximation of a complex Tibetan idea or the deliberate use of an English phrase. This type of back-and-forth enriches the process, she says: “I’ve had the opportunity to go back and say, ‘is this a concept that only makes sense in English, or is there a Tibetan equivalent?’ It’s been just an incredible education in how we can translate the Dharma.”

Ven. Damchö has always been involved in language and the written word. Before discovering Buddhism, she was a high-powered New York-based journalist. Sent to Hong Kong in the mid-90s to establish a news bureau, she was at the peak of her career. “I was doing very very well in all the worldly senses, traveling around Asia on an expense account, being the boss of the whole thing, “ she says. “It’s like everyone’s dream.” Despite her flourishing professional life and a strong network of relationships, she nevertheless felt that something important was missing: “All the ingredients of happy life were there, but it didn’t taste like anything.”

In 1997, she spent a year working as a freelance journalist, traveling around Asia, “trying to grope toward a sense of what would be meaningful and satisfying at the same time.” Eventually, she ended up in Nepal, where she did the requisite tourist circuit: trekking, rafting, and attending a 10-day meditation retreat. The retreat was led by Ani Karin, a Swedish nun in the Gelug tradition, and seeing another Westerner speaking to her situation was powerful for Ven. Damchö. “The combination of social and personal values, with an ontological explanation for why they have meaning and the specific steps to cultivate those values for me was absolutely compelling,” she says. She returned to Nepal several times to study further, and took monastic vows in 1999.

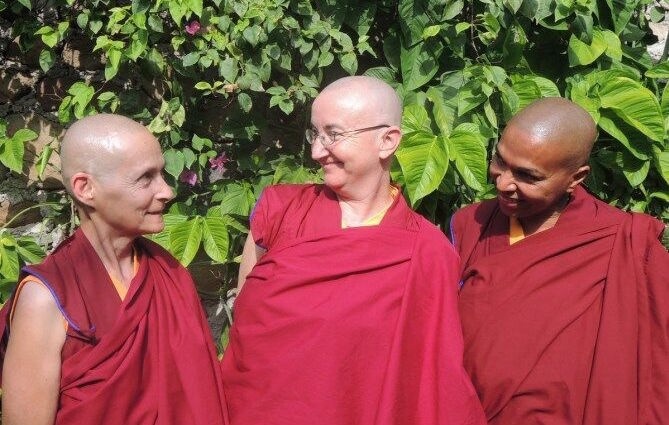

For a few years after ordaining, Ven. Damchö divided her time between Nepal and the University of Madison-Wisconsin, where she studied Sanskrit and Tibetan and worked toward her Master’s degree and Ph.D. During this time, she also began to wrestle with ideas of gender and the role of women in her chosen religion. Understanding that the Buddha is always presented through the lens of history, she initially worried that she might see something uncomfortable if she looked too closely at the history of gender dynamics. “I was willing to look at it out of the corner of my eye, but not to turn my full attention to it,” she says with a laugh. “We’re seeing [Buddha] in representations that have been handed down historically through patriarchal societies, so who knows what we’re going to see if we look?” But she says that after working on her Master’s thesis, which explored ethics and gender in Vinaya (monastic code of conduct) narratives, “I found so much that was so incredibly encouraging and empowering.” In 2007, drawing on her explorations of women’s roles, she requested to establish a small trans-national community of nuns. She now lives and studies in Dharamsala, India with three other nuns, one Mexican, one Swiss, and one Puerto Rican. “I realized that we can’t wait to appear as a community that needs to be integrated into the [Tibetan] sangha,” she says. “As Westerners, we need to learn how to live together in a community.”

The four women focus much of their attention on Spanish-language Dharma teaching. Through a website, Comunidad Dharmadatta, they offer weekly Spanish-language webcasts, courses in Buddhism, retreats, and guided meditations, free of charge. They are now working on developing a more formal four-year study program. “There’s a tremendous upsurge of interest in the Dharma in Spanish-speaking countries and there are relatively few teachers who are addressing that thirst,” explains Ven. Damchö. She notes that the Internet-based format works well because practitioners in the Spanish-speaking world are dispersed geographically, although she hopes to establish a nunnery in Mexico soon, to accommodate women in that country who wish to go forth.

“One of the issues for us as Westerners is that in order to become a Buddhist nun, you already need to have a pretty strong independent streak, or you need to be someone who’s willing to go their own path. That doesn’t necessarily match that well with communal life,” she says. “What I started noticing very early in Dharma centers in Puerto Rico and Mexico is that people wanted to practice together. They are eager to practice together.” Ven. Damchö’s scholarship on the early Vinaya has been helpful; learning about communities of women from the Buddha’s time, “you have a model for a very intense communal life where it really is about letting go of yourself and everything you hold to be ‘mine’,” she says. Making a personal commitment to live in a community of women matters not just because it supports individual practice, but because it is a choice made by the women themselves—not being sent somewhere by a lama, or following orders, but organically coming out of their own aspirations.

His Holiness the Karmapa has been vocal in his support for the growing public roles of female monastics in Buddhism, from establishing debate grounds and annual conferences to promoting individuals in particular ways. “He’s giving these nuns the opportunity to do something that they can excel at, that’s very visible. It builds their confidence and it allows the monks to see [their progress],” says Ven. Damchö. At one of the recent nun’s debates, His Holiness told Ven. Damchö that she would speak at a ceremony commemorating the 16th Karmapa in Bodh Gaya. “He had me up there talking in front of 12,000 people at this extremely important event for the lineage, launching all these publications and having this big, very visible thing,” she laughs, still a bit overwhelmed by the memory. “He put me on the stage and I know why . . . he wanted people to see: hey, women do stuff!”

See more