Collection of Scripps College, Claremont

For much of Korea’s history, Buddhism has been a powerful force influencing the culture and spirituality of the Korean people, from the royal court to common society. During the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897), however, the court officially espoused neo-Confucian doctrines, which focused on maintaining social order and honoring ancestors as a means to cosmic harmony. The government turned against Buddhism, withdrawing its patronage from Buddhist temples and often oppressing those who practiced the tradition. Buddhist temples moved from the cities to rural and mountain communities, where Korean Buddhists found creative ways to continue their practice, often incorporating new imagery and deities.

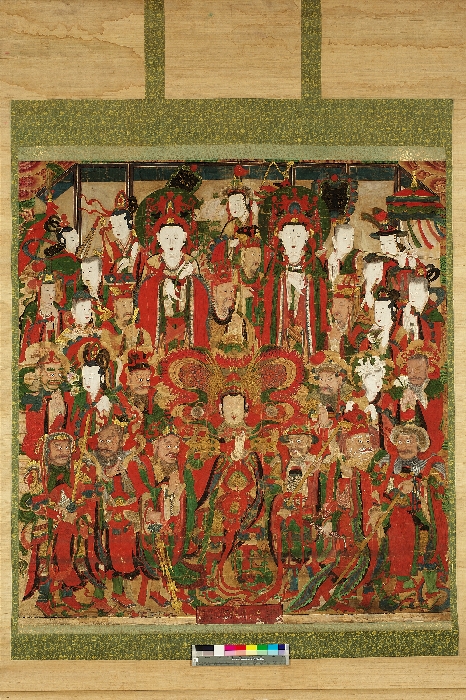

From the 18th century, a new type of painting seems to have emerged that focused on groups of guardian figures, often not immediately recognizable as Buddhist deities. These guardian paintings, or Sinjung Taenghwa (신중탱화, literally a “a host of spirits hanging painting”), are one of the most intriguing types of Buddhist art to have evolved in Korea. Examples are relatively rare, but there are a few in museum and college collections, including the teaching collection of Scripps College in Claremont, California, and they are worthy of further study as examples of the endurance and adaptation of faith under oppression.

The Scripps College painting, gifted to the collection in 2016, probably dates to the late 18th century. It is finely rendered in ink and colors on silk, although it has a layer of dry accretions on the surface and requires cleaning.The painting is in its original frame, with metal hanging rings at the top, and it apparently originally came from a Buddhist temple. A total of 12 figures are arranged in three rows: five in the back row, five in the middle, and two at the front left and right. Although there is a slightly larger crowned buddha-like deity in the back row, who appears to be flanked by two smaller crowned figures, these deities are not the central figures in this gathering. Instead, a slightly smaller figure with an unusual feathered headdress is positioned centrally, flanked by three fearsome warrior-like characters with Central Asian features and facial hair, and with a young boy holding a trident to the center right. At the front left and right are two Chinese courtier figures wearing formal court robes and headdresses and holding official scepters.

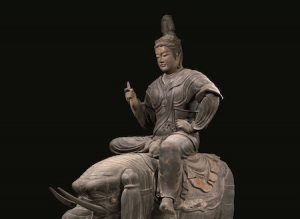

The intriguing central figure wearing a feathered headdress and holding out a sword is Tongjin Posal, a bodhisattva who is charged with protecting the Lotus Sutra of the True Law (Skt: Saddharma-pundarika), one of the most revered and influential of all Mahayana Buddhist texts. According to the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton University Press 2013), the Korean name Tongjin (童眞), written with the Chinese characters for “youthful” and “authentic,” is a translation of the Sanskrit name Kumārabhūta. The term is used for a youthful form of bodhisattva, and often specifically for Manjushri, who is perennially youthful. This divine child can either be associated with the Hindu deity Brahma, who is said to have given birth to four such divine boys or kumara, from his mind, or with the lesser Hindu deity Skanda (also known as Kārttikeya), one of the sons of Shiva. In the Buddhist pantheon, Skanda is one of the eight generals subordinate to Virudhaka, the Buddhist Guardian of the South who serves as a guardian of the Buddha’s teachings.

National Museum of Korea*

In Hindu iconography, Skanda is typically depicted as eternally youthful and riding a peacock. In Korean guardian paintings, Tongjin is depicted with a young face and with feathers fanning out from either side of his head, like the tail of a peacock, so the association with Skanda seems likely in these guardian paintings. However, Brahma is also present in these groupings. The National Museum of Korea has a similar Sinjung Taenghwa (accession number: Deoksu 449), which also features Tongjin at the center with an elaborate feathered headdress. According to their description of the painting, the Hindu gods Brahma and Indra are depicted above Tongjin, to the left and right, forming a triangle with the figure of Tongjin. All around them in the upper section are various heavenly gods and goddesses, shown with radiant Chinese facial features, perhaps representing Daoist and Confucian deities. Below them are armed guardian figures with darker faces, larger eyes, and facial hair.

(1392–1897), dated 1891. Ink and color on cotton (121.92 x 137.16 cm).

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art has two similar paintings entitled Bodhisattvas of the Protection of Buddhist Doctrine in its collection. The example shown here depicts 16 figures surrounding a similar central figure, whom the museum identifies in its Curator Notes as Witaecheon, a Korean representation of Skanda. The notes further explain that this deity “was made protector of the Buddha’s law at the scene of the Buddha’s death, and that he was worshipped especially as a guardian deity of Buddhist temples. He was also venerated as a leader of the celestial army or as a deity who removed all evils.” He is similarly flanked by four guardian kings, but also present are beautiful women, boy monks, and two elderly men: on the right, the elderly man is a mountain god, who is said to repel evil spirits, eliminate disasters, and grant fortunes, and on the left a kitchen god who protects families and traveling family members. The addition of local folk deities and Chinese Daoist deities to an already iconographically complex grouping was apparently common in this type of painting.

Although sculptures and paintings of principal deities were still displayed in Korea’s rural temples during the period’s official oppression of Buddhism, Sinjung Taenghwa seem to have occupied a prominent place in the worship practice of rural Buddhists. These paintings were typically hung on the right-hand wall of the main halls of Buddhist temples and bear inscriptions of the names of donors in the community who commissioned them. Tongjin (or Witaechon), the various heavenly deities and the armed guardians who comprise the sinjung, or “host of spirits” are not central figures in the Buddhist pantheon and so hold lower spiritual status than buddhas and bodhisattvas. In fact, certain figures included are not Buddhist at all, but Hindu, Daoist, and from Korean folk traditions. Perhaps these more lowly guardians were more immediately accessible to laypeople than buddhas and bodhisattvas, and served as mediators between the people and the higher deities. By welcoming these deities from diverse religious traditions into the main halls of their temples as guardians of the Buddhist teachings, it seems likely that Korean Buddhists were using these paintings as a means of rallying as much spiritual protection from other religious traditions as possible to preserve not only themselves, but also their precious faith.

* Buddhist Guardian Deities (National Museum of Korea)

References

Buswell Jr., Robert E. and Donald S. Lopez Jr. 2013. Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.