“Whoever speaks in primordial images speaks with a thousand voices; he enthralls and overpowers, while at the same time he lifts the idea he is seeking to express out of the occasional and the transitory into the realm of the ever-enduring.” – C. G. Jung (Jung 1971, 47–48)

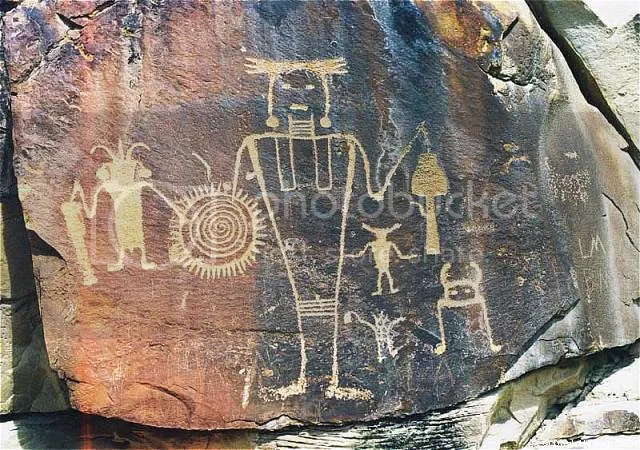

Ever since the era of Shamanic cave art, we have endeavored to capture and convey invisible information in a visible symbolic language that has been brewing since the dawn of creation.

As an artist, a painter, a “manipulator of symbols to achieve a change in consciousness” (as the writer Alan Moore puts it*), I write in order to understand the power of art, to understand how imagery heals and why it has been used as a tool for liberation and why it is significant to know why. And while it is true that the ultimate nature of reality does not require “thinking” to “know” it, in the same way that we do not need to think about how our bodies work to know that they do, the knowledge of the “how” adds to the profundity of appreciation as well as a clearer understanding of how to keep them healthy. And we are IN bodies. By apprehending their mechanics, we facilitate transcendental practices.

As Buddhists, we’ve been encouraged by the Buddha to embrace critical thinking, as well as by HH the Dalai Lama, himself an advocate of scientific curiosity. I am also influenced by my earliest Buddhist teacher, the highly respected Geshe Namgyal Wangchen, who lived with us in London during my childhood. He was an early proponent of the marriage of ancient Eastern wisdom teachings and today’s Western scientific practices, and of the ways in which we can integrate them, learning and evolving from both.

Over the last few years, research on the brain, consciousness, meditation, and creativity has been shared increasingly. Our awareness has deepened regarding the brain’s physiology, its improved connectivity after art production, and the de-stressing and pleasure hormones released whilst both looking upon and creating art, not to mention its role in healing emotions and importance in spiritual practice.

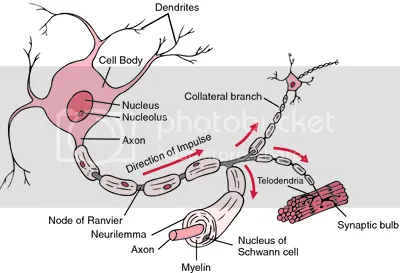

Expounding upon my last article,** here is a quick recap of the biology of repetition in meditation.

With new information, the brain creates new connections, new bridges.*** Author Malcolm Gladwell popularized the idea that 10,000 hours of practice makes anyone an expert, meaning that the more practice one does, the more proficient one becomes. This is because myelin wraps its protective fatty sheath-self around the axon (the “bridge”), incrementally speeding the transmission of information in the brain, which in turn transforms something practiced into an action that appears effortless. Repetition morphs the brain matter to create something that becomes subconsciously “instinctive.” And as the brain itself doesn’t know the difference between a physical action and a mental one, imagining is just as real to the brain as our bodies experiencing something because our internal perception is the only reality our brain knows. Our experienced world is purely neurological perception and projection.

“What you think, you become. . . . What you imagine, you create.” (The Buddha)

Repetition, willing or unwilling, imagined or otherwise, hardwires itself into the brain, particularly when combined with an emotional state. This can be argued as the reasoning behind our negative patterns, our neurological kleshas (negative emotional reactions; see Part 1), but also as the biological reasoning why “faking it until you make it” works, even when practiced purely in our minds. This surely is partly why invoking a deity through meditation by using imagery (both physical and mental) works to facilitate a change in neural structure. We are imprinting an image on our gray matter—an ideal psychological attribute that we wish to attain—and with repetitive practice, we will “become” this.

Art is fundamentally significant in acting as a road map for the individual.

Thangkas, a visual, spiritual storehouse of wordless information once the language has been learned, are mnemonic devices that communicate directly with the mind without the need to intellectualize, and facilitate ease of internal visualization. I often refer to ancient imagery for deep wisdoms, but it should also be remembered that many of the Eastern images we attach to and sometimes romanticize in the West were also culturally influenced artistic interpretations appropriate to the age that have been recopied for centuries.

Spontaneous art manifests from our unconscious mind, however, revealing secrets to our consciousness, both personally and collectively. This no longer has anything to do with repetitive practice and is more to do with something at a hidden level. During the art-making process, our mind roots around in the recesses of the brain for colors and symbols it sees as appropriate in the moment, which then become manifest through the body. Seeing the resulting image externally is enough to trigger neurological shifts. Understanding the color and symbolic language of the collective subconscious facilitates the bringing of the unconscious to conscious awareness, giving us the opportunity to learn more about ourselves and address whatever may need addressing.

Channelers of art, child prodigies, and savants produce something that is trans-individual and that could not have been achieved through one lifetime of practice. Possibly it is the result of a memory being carried over from past lives, or of information received from beyond the constraints of their own mind. We live in a “4 per cent” universe, in which 96 per cent is unknown and invisible. This is surely the “nothingness” of Eastern spirituality. Science now knows this void to be anything but empty, validating in a Western way what the ancients seemed to know inherently. This void permeates Every Thing. Our brain and our earth-based biological meat-sacks are 96 per cent void. The perceivable remainder is 4 per cent condensed, superpositioning energy, which is still essentially void and apparently designed to fine-tune itself to receive information from a collective psychological/emotional etheric field and quite possibly, from the “void” itself. Information in the form of energy (as neuroanatomist Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor puts it****) floods our primed minds, and consequently, breathes life into something we create. We place ourselves in a receptive flow state and bring something into this frequency which resonates with the viewer and feels alive.

So, while symbols impart information and some traditions should be kept and honored, it would surely also behoove us to pay attention to an evolution of transmission, taking the modern collective unconscious into consideration. The stunning art of HH the 17th Karmapa is a case in point, as he himself seems to have diverged from the traditional into a unique and personal expression of the Divine, befitting today’s context “rather than rigidly preserving old ways.”*****

As Carl Jung said, art is “constantly at work educating the spirit of the age. . . . All art intuitively apprehends coming changes in the collective unconsciousness” (Jung 1971, 82).

As an artist, I witness my journey through the art I’ve produced, and deepen my practice through what I feel compelled to paint. Sometimes, I viscerally feel I am drawing in an energy; sometimes, I’m deepening my relationship with an archetype as purely a psychological reflection of my own being, simultaneously aware that images are gifts manifested through an artist that are indispensable to our evolution. When I get out of the way and into that flow space, I know I become a conduit.

While there remains the big “art debate” in the commercial forum and while in some cases it is probably prudent to remain discerning in what constitutes art, especially spiritual art, we are nonetheless producing and seeing more and more very conscious, shamanic, healing imagery, each “conduit” with a unique artistic expression. These visual messages manifest from the invisible to affect an individual, and this in turn impacts the collective. This, to me, is very exciting, and also the reason why it’s important to pay attention to this evolution, which is just as significant as the mnemonic thangkas at the time of their transmission as these, too, are culturally influenced artistic interpretations of deep wisdom appropriate to the age that acted as a road map.

References

Jung, Carl. 1971. The Spirit in Man, Art, & Literature (Collected Works of Jung, Vol. 15). Princeton University Press.

See more

*The Mindscape of Alan Moore

**Deconstructing Bridges and Forging New Highways with Dharma Art – Part One

***Neurons, Nerve Tissues, & The Nervous System

****My stroke of insight

*****Official Website of the 17th Gyalwang Karmapa

Ti Campbell-Allen is a member of the Dakini As Art Collective. To learn more about Ti, her work, and Dakini As Art, please visit her website Silk Alchemy and Dakini As Art.