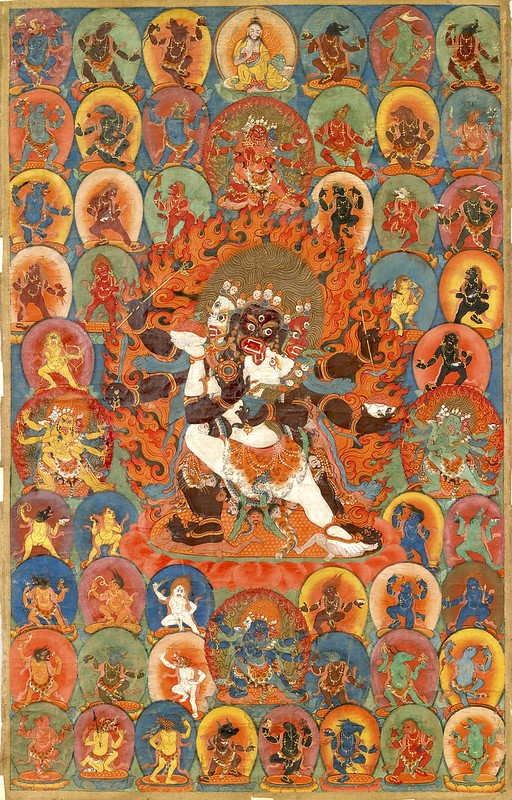

A most amazing mural is painted on a six-meter-high cylinder on the second floor of Dungtse Lhakhang in Paro, Bhutan. The temple was designed by the Tibetan yogic adept Thangtong Gyalpo, (1385–1481?) better known in legend and lore as The Iron Bridge Builder, a great engineer who erected iron-chain bridges across raging rivers throughout Bhutan. Dungtse Lhakhang has an unusual three-story structure, with a square ground floor, a circular second floor with a towering cylinder inside, and a third floor consisting of a square platform within a circle. The mural was commissioned in the 19th century by the 25th Je Khenpo, head abbot of all monks in Bhutan. It depicts a yogic vision of the after-death state centered on a wrathful form of Guru Padmasambhava known as Gong Due.

Lhakhang in Paro, Bhutan. Animal-headed dancers ring the column. Photo by Shuzo

Uemoto, 2007

The mural includes depictions of 28 dancing animal-headed, wrathful female bardo deities (Tib. khandum) from the Gong Du Bardo Shitok text, a terma (treasure) revealed by the terton (treasure revealer) Sangay Lingpa (1340–1396). Such treasures include objects, texts, teachings, and practices hidden by Padmasambhava for the benefit of future generations, during which times the treasures are revealed. Dungtse Lhakhang can be visited only with permission, and even then fabric covers protect the murals and there is no light aside from the gentle glow of candles. However, when our team from Core of Culture visited to document the mural, we were allowed to remove the fabric and use camera lighting.

Bhutan. Photo by Shuzo Uemoto, 2007

Like an architectural donut, the soaring central column and the encircling outer wall combine to form a circular walk way less than two meters wide. Lighting and photographing the rare dance figures on the mural was therefore challenging. Shuzo Uemoto, a photographer from the Honolulu Museum of Art, skillfully managed to document the entirety of the cylindrical mural, from top to bottom. There is of course optical distortion, but all of the images we recorded are of very high resolution, meaning scholars and others can enjoy extreme close-ups of the curving surface.

Uemoto, 2007

The 28 animal-headed dancers are a kind of foundation for the entire cylindrical mural; a point of entry into visions of the bardo. The bardo is the Buddhist after-death state; the process of disengagement from phenomenological being toward nirvana and enlightenment, or a return to the karmic cycle. The Tibetan Book of the Dead is a precise yoga of how to go through each phase of dying properly, with consciousness and understanding. Various enlightened masters, particularly those visionaries called terton, who discovered knowledge left for them by Padmasambhava, have variously and vividly described the bardo after-death state, just as they have variously and vividly described yogic journeys to Zangdok Palri, the Lotus Light Palace in another dimension.

The cylindrical mural at Dungtse Lhakhang is a vision of the bardo from such a visionary. The bardo itself is a progression of visions. Terton Sangay Lingpa revealed a text describing the visions in detail and an unknown painter executed what can only be understood as quintessential visionary art.

Dungtse Lhakhang, Paro, Bhutan. Photo by Shuzo Uemoto, 2007

Tantric meditations are yogic techniques that the adept carries out. Murals such as this one are instructions; teaching modalities. Like the temple at Tabo Monastery in India’s Spiti Valley, the floor pattern determines the path and the visual experience of the viewer/practitioner. From bottom to top, the figures are performing different acts. The wrathful deities are dancing and feasting on human limbs. At the upper reaches, serene deities in yab-yum posture ascend and escape time. The rhythm and madness of the dancing deities is the same as can be seen in certain Cham dances. When the dancers swirl, spin, halt, stop, reverse, and leap counter-clockwise, a vision of the mind activity appears, where form and formlessness meet, mingle, and share a core transcendent unity. At the psychic level of animal nature, instinct, innocent passions, and physicality are unleashed; this is where the dying person remembers, even recognizes the snarling monstrous gods, for the person knows those gods from years of seeing Cham. Infants nurse in the laps of their mothers as the monks in their masks speed by, one by one, year after year. In the death yoga, these dancing deities help us separate from this world.

When the process of dying is undertaken properly, the dying person will not be distracted by visions of these wrathful characters and their awful actions, instead the dying person will pass through this stage of individual dissolution with grace and the awareness that not only do our senses and personalities go away, but our instincts and life as a reflex of nature become a former way of being. These symbolic powers appear in the mural at the base of the column. The canons of bardo deities and the practices associated with them vary according to the particular text, and in relation to a central deity, which here is wrathful form of Padmasambhava, Gong Due.

The mural corresponds to a sand mandala design, as well as a painting of Gong Due surrounded by the dancing wrathful deities, both integral artwork components of the Thimphu Drubchen dance rituals, among the most sacred to the kingdom. Although different in form and medium, the sand mandala and the painting function in precisely the same way as the enormous cylindrical mural: as a blueprint for meditation. The visionary animal-headed beings become animal-masked monks, in real dances using the same steps: the leaping forward while looking back, the gyroscopic flailing, the procession of deities.

2007. Photo from Core of Culture

In the Thimphu Drubchen dance rituals, the sand mandala is used for communal and personal meditations over the course of two rehearsal weeks. Then the painting, in its specific parts, is telepathically imprinted directly upon the minds of the dancing monks by the je khenpo minutes before they dance. What dance or yogic practices that might have occurred at Dungtse Lhakhang are now extinct. The second floor circular walkway around the dancing bardo deities is virtual reality designed for the cultivation of consciousness. The gory hybrids in their tramping toss you up into the rising enlightenment of the Buddhas. Just looking as you walk around, your body contorts as theirs do, twisting out into a higher state of mind. Don’t be afraid. Get to know them.

empowerments during performances. Chorten Ningpo, Punakha, Bhutan. 2006.

Photo by Shuzo Uemoto

It should be understood that this whole exegesis, the mural in its entirety, is a yoga performed by one person while dying. It is Terton Sangay Lingpa’s visions of the luminous bardo that arise in the mind after death and reflect different aspects of the psyche. The dancing animal-headed khandum are performing a Gar Cham, a sacrificial dance, characterized by “always moving.” Mastering death as a visionary encounter with oneself, these particular archaic deities are always moving, always dancing. They never stop. These khandum are in their most wrathful form. Wearing ornaments of flayed skin, they eat flesh, tossing their heads in a spiraling dance. Every mudra (empowered hand gestures) they perform effects the subjugation of evil. The animal-headed dancing deities symbolize the divinity of our bestial nature. How fortunate to be human. To have life. To return.

Portions of this column are adapted from sections of Houseal, Dance and Art in the Dragon’s Gift, Orientations, Vol. 39, No. 1, Jan/Feb 2008.