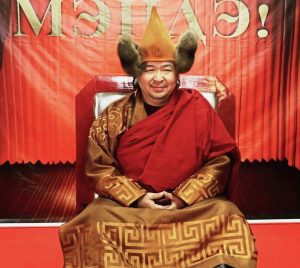

The dancing mind is another mind. In Vajrayana Buddhist Cham, dance is yoga, the dancing mind the whole point—the center of the experience. Monk-dancers are all ages, but throughout Ladakh, many are in their twenties. Not all dancers become fully ordained monks, or gelong. Not all gelong become dancers. Not all dancers become champon, the master of dance, and not all champon become umze, the music leader of the Cham ritual. There are various career trajectories in the monastic world, depending both on lineage and ability. Here is a story about a monk-dancer in his twenties.

These days, when Buddhism flowers freely in Ladakh, at the same time encountering and succeeding in a contemporary global economy, the religious administration is careful whom it cultivates to take on successive positions of leadership within a monastic order or monastery. It is a majestic responsibility that, among other things, entails the stewardship of Buddhist ritual dance—in some cases, dance recorded from the yogic visions of lineage masters and thereby constituting a skillful means to liberation of the mind.

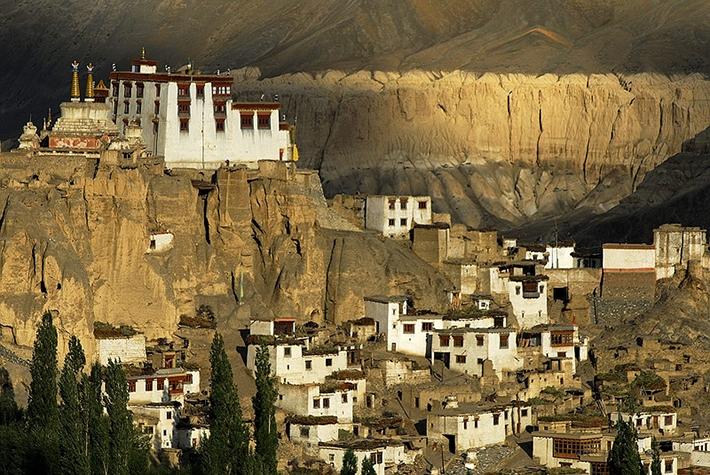

Fifteen years ago, at Lamayuru Monastery in Ladakh, the late dance and meditation master Sonam Kunga Rinpoche steered Core of Culture to its first work in dance preservation. It was then that we met Konchok Rinchen, a boy monk just ten years old. We produced a DVD of the young abbot, Rangdol Nyima Rinpoche, expertly demonstrating the specific steps of the Drikung Kagyu dances for posterity.

Over the years, Rinchen has studied philosophy, history, and ritual as well as dance, and has mastered the chanted recitation known as puja. His growing responsibilities enabled him to provide us with fuller assistance and allowed us gradually to acquaint him with the dance preservation methods and motivations of Core of Culture.

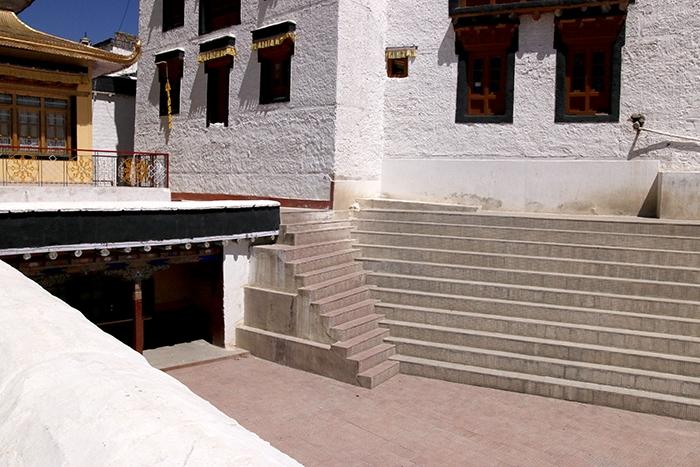

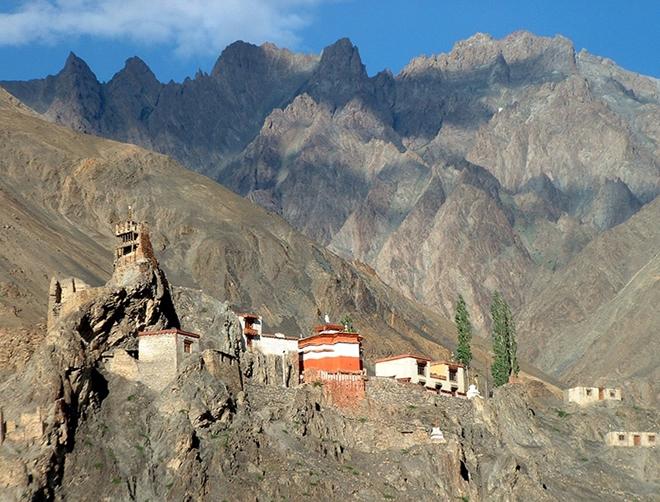

Traveling from Srinagar this year, we made a stop at Wanla, perchance to catch Konchok Rinchen visiting his hometown for the summer. Yes, Rinchen was there, and utterly surprised to see us, but we in turn were astonished to find him ensconced as the keeper of Sumtsek Temple and Wanla Monastery, a 12th century, three-storied tower and 14th century monastery—alone. He assured me that there is an annual 10-day period where 45 monks are engaged in making a mandala and doing puja. He had returned from dancing in the Lamayuru Cham ritual two weeks earlier.

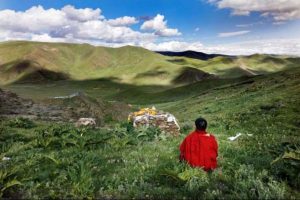

Mostly though, for the past three years it has been Konchok Rinchen, now a grown man of 25, drumming, reciting, and chanting by himself for up to five hours every day in simple fulfillment of ritual duty to the temple, deity, village, and religious order. Surrounding him are circa 12th century masterworks of Buddhist sculpture and mural painting, created by Newar and Kashmiri artists combining their artistic styles in an expression of Vajrayana realization. Rinchen’s resonant chanting of sutra and mantra reverberates in the ancient tower as he drums. The vibrations emanate, overlap, and transport the empowered syllables through the painted multitudes.

Rinchen moves with the natural grace that is the bearing of a real monk. It is not a vague, poetic reference to seriousness or serenity, but a true physiological condition cultivated by years of seated meditation, strict diet, and mountain life: a lowered center of gravity. It is from this deep center of gravity, this energized bellows, that the Cham dance extends gyroscopically into a meditative vortex as it spins and traces an unseen mandala within the mind and upon the earth.

Dance as yoga expands to become a moving embodiment of a visualized deity—such deities as adorn the walls and chambers of Wanla’s Sumtsek Temple, where Rinchen has meditated for three years. This ritualized life is the foundation of a monk-dancer, invigorated by breath, rhythm, sound, image, movement. The basis of a good monk-dancer is a good monk.

Rinchen’s body is attuned, a chamber for chanted vibrations of empowered syllables. In Cham, the body, speech, and mind come together in a highly integrated metaphysical technique. In a real monk, these are already together by design, trained by monastic habit. In one practice we saw in Bhutan, the future umze had done retreat in a cave for three years, reciting only the mantra of the deity honored in the Cham ritual. The richness and power of his voice afterward are like no other form of singing, like no other state of mind. The kinds of body-mind integration such monks possess provide a foundation for dance like no other form of dance.

Rinchen is a ritual adept. Every sound, every gesture, every use of symbols comes from understanding the symbolic meaning in practice. This is the expression of a mind functioning at a symbolic level. This is the body as symbol: full concentration of mind upon the supra-rational.

Rinchen had news for us: he was about to take his gelong vows at Lamayuru, and in addition to being installed at Wanla Monastery for another year, would one day study with the meditation master of Lamayuru, undertake a long retreat, and go on to become the master of dance, and ultimately, the chant and music leader of the entire Cham ritual. His trajectory is that of a monk able to carry the traditions forward with an authority that derives from his own thorough practice, his way of being, his mode of life. Rinchen is one of those selected to carry forward the dance.

The dances of the Drikung Kagyu are among the longest Cham. Cham is a tantric yoga. It is also a spectacle and a procession of the deities, wrathful and peaceful, that make up our psychic profile. These are the dances Rinchen now performs, and will one day be charged with overseeing and transmitting.

He invited us to his Tongo ceremony, during which he would offer a feast to his own villagers and all those who have helped him achieve his present position. Four of his friends, monk-dancers from Phyang Monastery, were coming, and Phyang’s Cham ritual would take place in one week. Rinchen asked us if there was anything from Core of Culture that we wanted to show them.

My colleague opened his computer to the DVD we had made 15 years earlier, Lamayuru Sanctuary of Dance, which shows the young Rangdol Nyima Rinpoche demonstrating specific Drikung dance steps—the very steps the monks were now rehearsing. Just as Rinchen had come of age, we saw that the Cham DVD had, too. It finds its use in the generation that followed it, not in the generation that produced it. The dancers watched the demonstrations intently and with humble good humor—it was a level of their own style of dance that they had never seen.

After the Tongo ceremony, we returned to Leh, stopping at the impressive precipice monastery and temples at Basgo. The creation of a Buddhist king and a Muslim queen, this great citadel of painted murals houses a colossal image of the future Buddha, Maitreya, perhaps the oldest in India. Two monks took care of the three lofty temples, and were accommodating when we asked to see the dance imagery in the 17th century murals, which represent some of the finest Buddhist art on the entire Silk Road.

Seeing our interest, one of the monks, Jigme Josphel, invited us to tea in his room, a simple mud structure with a small kitchen and a sleeping/work area. As Josphel made the tea, my colleague noticed how badly dry and cracked his feet were—it looked agonizing. Once the tea was served, my colleague asked if he might apply some ointment to the monk’s cracked feet. Josphel allowed it, and offered up one rugged and cracked foot.

“I remember when you thanked the son of the Chakar Lam in Bhutan for his outstanding dancing by touching his feet,” said my colleague, as he went to work like a battlefield medic and psychic healer all in one.

As the unorthodox therapy continued and Josphel could feel moist relief for the first time in months, he told us that he was a dancer at Hemis Monastery. Core of Culture Dance Preservation does what needs to be done to help ancient traditions—including the application of ointment to dancers’ feet. It is our destiny.