Endangered dance isn’t as well known as climate change or the extinction of animal species, but it is an equally real living expression facing existential crisis. Ancient is a wonderfully evocative and embracing word, yet not so specific. What characterizes an ancient dance? How do dances survive? Many strategies are at play when surviving military actions, religious oppression, and natural disasters; didactic problems, migration, and climate change. This article discusses three challenges that an ancient dance must overcome in order to survive a changing world. An ancient dance is one that has already survived political change; an ancient dance has survived changes in sponsorship; an ancient dance has survived changes in organization. This article will look at these three markers of continuity.

In other words, ancient dances can outlast governments, religions, and societies. For example, dances from Japan’s samurai era, such as Noh, are no longer performed under a governing shogunate, nor are they funded by aristocrats. The dances have nevertheless continued for more than 700 years. Every ancient dance tradition finds itself having to confront these three temporary forms: government, funding, organization.

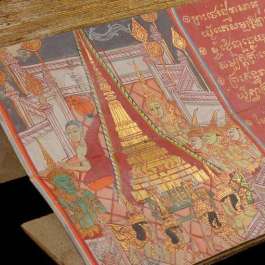

comprised of three hour-long dances, 2006. In Tamzing, Bhutan, both monastic and lay versions

of this great ancient dance are maintained. Photo by Gerard Houghton for Core of Culture

The Himalaya can be considered the geographic stretch from Afghanistan to Bhutan, including Pakistan, Kashmir, Ladakh, Zanskar, Himachal Pradesh, Spiti, Nepal, and Mustang. This list of modern countries and territories brings to mind an onslaught of national rivalries, tribal tensions, independence movements, and territorial claims in conflict. The ancient dances surviving all this current instability are doing so at remarkable odds by being true to the performance of their inherited embodied spiritualities. The Himalaya is volatile.

The 20th century saw the discovery, publication, and distribution of ancient secret texts like no other era before it. Readers of these circulated and translated texts, along with practitioners of extant traditions, form an international community of practice, scholarship and instruction beyond original geographic boundaries. As the modern nations of the Himalaya, once all kingdoms, now none save for Bhutan, struggle to sustain complex identities while landlocked between China, India, and Pakistan, it will be indicative to see which dances survive the inevitable political tides and changes; and which face extinction. Surviving changes in government characterizes ancient dances. These changes, being often upheavals, also endanger dances. So now is a time for an ancient dance to act like one, to do what it has done before, and adapt to tumultuous times like water.

Economic disruptions impact ritual performance within the often-poor communities where ancient practices are carried out. Prajwal Vajracharya is a 35th-generation tantric Buddhist priest from Kathmandu, a city beset with social, environmental, and economic challenges. Prajwal built an authentic Newar Buddhist temple (mahavihara) in Portland, Oregon, and recently celebrated the 12th anniversary of its founding. Prajwal’s father instructed him to take the secret tradition to the world and make it public. Prajwal is the first tantric Newar priest to function internationally. He founded a temple outside of Nepal, achieving viable support for his ritual and priestly dancing work internationally.

Prajwal, the foremost exponent of the oldest known Buddhist ritual form, has succeeded economically in breaking away from Nepal, and is thriving. This is one exceptional contemporary example of an extraordinary individual. Throughout the Himalaya now, a lay performer of rituals, a healer, an oracle, a shaman, or a priest, would be likely to have another paying job as well to make ends meet.

A Day of Rare Buddhist Dances, 2009. This is a Newar Buddhist

charya nritya yogic dance more than 1,000 years old.

Photo by Jonathan Greet for Core of Culture

It is not uncommon in the continuity of ancient dances that periods of economic challenge are met with financial austerity and simplification of actions. In fact, this return to essentials is often the congealing power necessary to sustain, conceal, continue, and from which to carry on and rebuild.

Nearly all ancient dances and rituals in the Himalaya are religious. This means that, at some original point, a religious authority figure led the activity. The farther back in time, the more often the religious and political leadership were a single entity. The split of political and religious authority is often the first organizational shift that an ancient dance will experience. This might also be a royal and religious split. There is no royally sanctioned dance in the Himalaya as all the kingdoms are gone. Even the Kingdom of Bhutan is now a parliamentary democracy and semi-constitutional monarchy in which the figure of the King is mainly ceremonial. The replete context of royal behavior, etiquette, and programming is gone, as also in Nepal, and Ladakh, and Kashmir.

Some Himalayan dances have gone extinct from religious oppression after the loss of protective patronage; some have gone stale or extinct by being reclassified as “folk” dances associated with no particular site or location. Government codification usually encourages a standardization of styles that were more freewheeling in actual practice. Some groups have re-organized, as have Buddhist monks, making monasteries economic mechanisms of a new kind, without political power, with a renewed appreciation for the value of the rituals and dances as skillful means to connect with the world, and as a way to teach. Modern tourism impacts the economic context of Buddhist ritual dance, endangering the integrity of the dances by re-valuing them as commodities rather than as a spiritual heritage.

All along, the monastery has sustained institutional support for the large canon of dances maintained for a thousand years and more. At the local level, village communities have passed down dances for hundreds of years. Chinese ethnographers have a useful term to describe practices so old they are equal to collective memory: “handed down from ancient times.”

Japanese Noh theater offers a clear example of organizational change. At the start there were troupes: each ensemble had everything needed, a main actor, a secondary actor, a flute player, two drummers, and a chorus. Later, each art established its own guild: of actors, of costumers, of flute players, of drummers. Now it is a headmaster system, with each of the five traditional schools of Noh headed by a hereditary leader and entrusted with the stylistic integrity of the school among all the performers. There is a question of transition of organization now ongoing in Noh, due in part to economic and social change. It has become a matter of whether Noh is better produced in the traditional manner or whether to allow modern theatrical producers to finance and position it, more as Kabuki has done.

Surviving political change, economic change, and changes in organization define the survival of ancient dances, something we can see today happening before our eyes. These challenges confront all as life and time roll out; they are not unique to old dances. Ancient dances have a habit of surviving change. Taking a moment to consider how these changes impact something like Buddhist tantric ritual adds living context to our understanding, and admiration for those who keep ancient embodied teachings . . . embodied.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Secret of the Golden Flower, Part One

Noh Now

Three Aspects of Buddhist Dance

Performative Iconography, Part One

excellent, and relevant parameters to consider for other ancient forms. will share