Over the course of several days in 2009, I had the great fortune to visit the Buddhist cave temples surrounding the oasis town of Dunhuang in northwest China with Robert Y. C. Ho and a small group of conservators. Dunhuang was a caravansary along the ancient Silk Roads, via which Buddhism was disseminated, and the 492 painted and sculpted Buddhist caves of Mogao are masterpieces of their own variously and highly stylized painting traditions.

Although Buddhism does not enjoy a reputation for being a dancing religion, it does in fact boast many dance forms, and Buddhism’s relationship with dance is ebullient in the murals of the Mogao Caves. These dance depictions were created from the 4th until the 14th century, a process outlasting a thousand years of political upheavals in both China and Central Asia.

Before our trip to Dunhuang, Wang Xudong, the associate director of the Dunhuang Academy, asked each of us in the small party which of the 492 caves we wished to see. I immediately contacted Mme Wang Kefen, the foremost authority on the dance imagery in the Dunhuang caves, where she had conducted research for many years, and she gave me a list of relevant caves. As nobody else submitted a list, in addition to seeing many important caves that are significant in their own right, we received a comprehensive review of the dance imagery at Dunhuang. No Western dance scholar has studied the dance imagery of the Mogao Caves in as much depth as I was allowed to do, for which I am grateful to Robert Ho, Wang Xudong, and Wang Kefen.

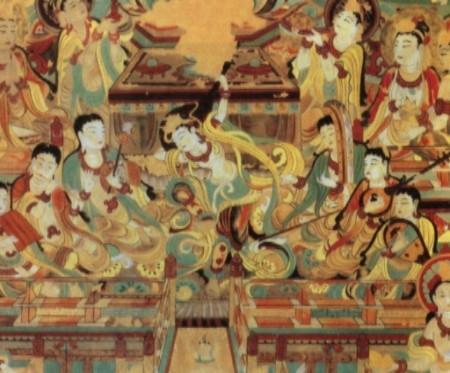

Wang Yuxing, 2010. From Core of Culture

Now aged 90, Wang Kefen is the author of four books on dance at Dunhuang and a fellow of the Dunhuang Academy. She is also the author of respected and much-translated histories of Chinese dance. She began studying art history in 1956, and through that study and her own determination, established the field of dance history in modern China. The year after the study trip, I had the good fortune to be able to meet with her in person, in Beijing.

Communication with Mme Wang was in part intuitive, as it is with dancers, based on gestures, facial expressions, tone of voice, and visual aids. Not only is Mme Wang an encyclopedia in herself, a “library on fire” as the Indonesians say, but she had an actual library of dance imagery in Chinese fine art laid out for me. Both of us being dancers, neither hesitated to demonstrate an arm or body movement. What follows is an edited version of our conversation.

Wang Kefen: Dance is an art of morphology—it defies the written word—hence artistic depictions become valuable. Dance activities have been present in every aspect of existence since primitive times, but it is only in China that the history of dance has been continuously recorded, both in words and in images. One of the challenges of translating my books is that they are full of ancient quotations, difficult even for Chinese to understand. The dance paintings at Dunhuang reveal a fixed pattern in terms of aesthetics, although they differ in costume, style, and gesture. There is inevitably at least one [painted] Buddha image in every cave, usually placed in [the midst of] a scene with adoring crowds, and a stage that is based on an emperor’s stage. I have seen this type of stage in Japan—it might have been used for Bugaku dance.*

Dunhuang. Tang dynasty (618–907). Image courtesy of Wang Kefen.

From Core of Culture

Hatsukaichi City Department of Environment and Industries. From Core

of Culture

Joseph Houseal: I have seen inside the Forbidden City, the World Monument Fund’s restoration of the Qianlong emperor’s [r. 1735–96] private stage for an audience of One. That two-part stage was nearly identical to the depictions in the caves, and indeed to any number of Japanese Buddhist temple stages, which designs are Chinese in origin. In fact, the same Japanese ruler, Shotoku Taishi, in the 7th century was responsible for importing Buddhism, Bugaku, and architectural styles into Japan from China.

WK: There is a recurring image of the Western Paradise at Dunhuang in which an elevated Buddha is attended by holy courtiers, entertainers, musicians, and dancers, painted lower down. Right at the top, “sky spirits” called feitian fly, doubtless in imitation of old dance forms. These dancing images are found not only at Dunhuang, they are all over China in many cave sites. I have traveled and studied the Indian Buddhist cave sites at Ellora and Ajanta—no flying feitian! The movement of these airborne devas and their invention originate in Central China.

JH: Could the feitian in general possibly be related to archaic Daoism and the traditions of the Daoyin tu** energetic gymnastics? Those exercises were certainly practiced in court by the time of the Northern Wei dynasty [386–535], when there were already feitian at Dunhuang. There were Chinese Buddhist aristocrats in the 3rd century who were well versed in the Daoist physical arts, and Daoist visualization methods attained a refined articulation with the Shangqing school of Daoism in the 4th century, emphasizing a visualized microcosm and an inhabited mystical heaven with visualized characters moving about within it. Some of the feitian movements are strikingly similar to Daoyin tu gymnastics.

WK: Interesting idea. No one really knows the precise origin of the feitian movements. For many decades now, the idea in China has been that “folk dances” represent the ordinary people, and so they should be done “only by the best” and have been adapted into a professionally trained culture of “folk dances” for the stage, with dancers trained at dance academies. This is what the Chinese people know as folk dance. But attitudes toward the minority nationalities in China are really changing, and nowadays the emphasis is on giving the dance back to the people and bringing forward real village level transmission of old dances.

JH: Do you think there is a connection between China’s minority nationalities and the dances depicted at Dunhuang?

WK: Everything you see in the Dunhuang caves has been shown to be based on real life examples. All the instruments have been carefully reconstructed and shown to be real. I believe the dances are real, too.

JH: There seems to be at least two, maybe three, basic categories of dance depictions: the early Wei dynasty depictions, the Tang dynasty [618–907] heavenly court scenes, and scenes that look like village people dancing. Was there some kind of actual aristocratic dance assimilated from folk dance and other practices? That, after all, is how classical ballet came about in the West.

standardized style of painting dance. Tang dynasty, 781–847. Image

courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy. From Core of Culture

WK: It’s complicated. The Chinese have been performing collections of dances since the ancient Shao dance written about by Confucius, so assimilation of different dances generally is an issue and one that is based, primarily, on people’s taste and desire to see new dances. The celestial dances at Dunhuang are both Buddhist and aristocratic assimilations. Did you see one scene where a nomadic dancer spins on a small circular carpet off to the side and below the Buddha? And another, “the brown family,” where a family is dancing? There is no audience, so that is a real life dance. Folk dance doesn’t have an audience, it just has “folk.” The audience is key. From ancient times, the emperor had his own dancers—lots of them. Aristocrats had their own dancers—lots of them. Even well-off poets and gentlemen had their own dancers. The dancers were mostly, but rarely entirely, of the same ethnicity as their owner.

JH: Owner?

WK: The Wei and Tang were slave societies, and the dancers were slaves. They did the dances their owners wanted, whatever their origin. In some of the Tang paintings you will see an audience, a courtly one and a celestial one. The courtly audience looks down, just as in a court. Each patron likely used their own dancers as models, part of the overall flavor of an individual cave. It was not until the 9th century that the stage was elevated and the courtly audience looked up.

JH: So why do the Tang celestial court dancers look so much more standardized than the Wei dynasty images, which also coincides with slave society?

WK: The Wei dynasty images are not slaves; they are real Silk Road dancers. The Wei painters introduced the architectural placement of dancers with flying feitian at the top, in heaven; praising, deified dancers in the middle, on earth; and people at the bottom, in “low-earth.” I say “deified” in the sense that the entire scene is deified [by the presence of the Buddha]; gestures themselves become deified. These early paintings reveal a mutual influence. Central Asian depictions of Chinese feitian appear, and newly refined Chinese-inspired depictions of nomadic dancers. These express the first shock meeting of Chinese and Silk Road dance influences. The nomads, including the Mongolians, did not have a stable court life or culture. It is fair to say that a new Buddhist style was created when the nomadic dancers gave inner expression and a kind of realism, while the Chinese dancers gave refinement.

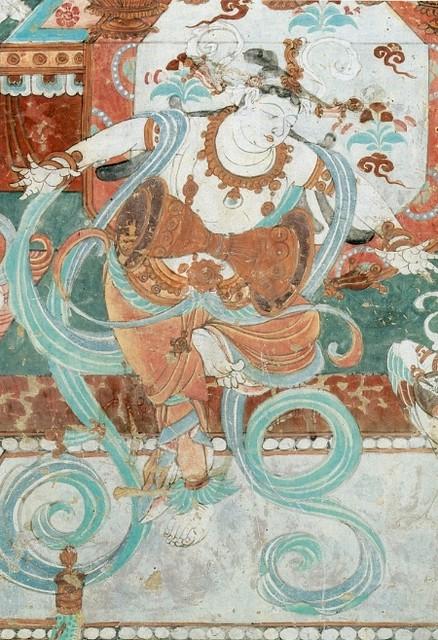

Northern Wei dynasty, 485–534. Freedom of

movement is matched by freedom of expression

in one of many choreographically intriguing

dance images from the Wei dynasties. Image

courtesy of Wang Kefen. After The Complete

Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes, Vol. 17,

Paintings of Dance, The Commercial Press,

Hong Kong, 2001, p. 27

*Repertoire of dances of the Japanese imperial court, derived from traditional dance forms imported from China

** Daoyin tu literally means “Diagram of Guiding and Pulling”; daoyin is a traditional type of Chinese breathing and energetic exercises, with the earliest forms being codified during the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE). The Daoyin tu was discovered among the burial objects at Mawangdui, near Changsha in Hunan Province, and dates to around 168 BCE.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Dance at Dunhuang: Part Two – The Case for the Feitian

Dance at Dunhuang: Part Three – The Sogdian Whirl