(c.1600-c.1046 BCE). Sanxingdui is the site of one of the world’s great archeological

discoveries, revealing jades and bronzes from the ancient Shang dynasty.

Image courtesy of the Sichuan Province Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology

Tracing non-Buddhist and pre-Buddhist elements in Buddhist practice is a fascinating endeavor. Did tantric Buddhism absorb other forms of ritual and behavior? The astute early explorer of the Himalayan Buddhist world Giuseppe Tucci understood that the appearance of dance in tantric Buddhist art and ritual was a marker of antiquity, and of an earlier, archaic religion. The notion that “inside every religion, is another religion” is hardly controversial, and the Bon religion is often used as a catch-all for anything undetermined or culturally Tibetan. There is some excellent scholarship on Bon. Dr. Samten Karmay has published translations of Bon dance manuals. However, Western scholars often come with preconceived notions of “religion” and “dance” that are not synchronous with Asian or ancient societies.

Note how the mask would rest on the sorcerer’s shoulders.

Image courtesy of Sanxingdui Museum

Buddhist practices are alive, unbroken for hundreds, even thousands of years in a number of regions; still extant or living in the contemporary world. This is extraordinary. As we seek to understand more about how Buddhist dance and ritual practices have developed over the millennia, there are many extant examples of Buddhist dance and ritual with ancient roots. Core of Culture, the organization I direct, has been working for more than 20 years within Himalayan Buddhism, and has produced abundant documentation of this heritage.

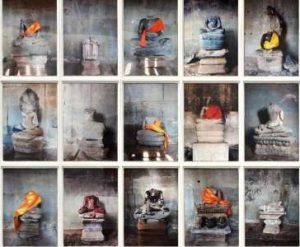

Photo by Jonathan Kendrew for Core of Culture

After stumbling on a subject of Chinese academic cultural scholarship—wu nuo, or shamanistic exorcism—I was surprised to realize that Core of Culture had 20 years of research to support a Chinese academic idea. Exorcism here is meant in is plainest sense: to get evil out; to keep evil out. As such, an auspicious blessing is a type of exorcism as it is designed to protect. Terrifying and ferocious deities were needed to protect against dangers from a mysterious physical and psychic universe. Here, below, is the evolutionary ritual idea, based on 20th century archeological discoveries espoused in China and gaining wider appreciation.

Exorcism as performance by transported masked dancer (nuo) emerged as a prototype more than 5,000 years ago in late Neolithic China—memorialized in jade and later as incised bronzes, bronze sorcerer heads, and bronze/gold sorcerer masks—and went on to undergird and establish an identifiable culture of shamanistic exorcism throughout China, Tibet, Central Asia, Japan, and Korea through to the present day.

abstracted design work, and ritual exorcism masks, this jade is thought to depict a dancing half-beast

sorcerer, being at the same time the shaman as well as the protecting spirit.

It appears that the shaman is riding the divine beast. From chinadaily.com.cn

This is a huge sweeping statement about cultural evolution in Asia, and it is the basis of amazing ethnographic scholarship over several decades in China. And it might be true. According to scholar Piet van der Loon, Chinese shamanism and, later, tantric Buddhism were the formative elements in the representation of gods and demons by means of masks. Buddhism and Chinese shamanism are connected; one aspect of blurring the lines over the centuries between shamanistic sorcery, court Nuo, local customs, religion, and nuoxi drama. Martial arts are an integral aspect of drama and monasticism. A Chinese scholar would have a more holistic grasp of the true nature of movement practice in daily life. The word nuo implies a sorcerer, a mask, a dance, and drama. It is good to point out how dance is understood so seriously and of a piece with other respected elements. Dance is how deities and transported sorcerers move. Dance carries the ancient mask.

Wu is a Chinese term for a shaman, or sorcerer. Sorcery is distinct from magic in this way: magic implies the control of nature, like controlling the rain. Sorcery includes the visualized or otherwise experienced reality of another being that was not there before; a being conjured or summoned. “Shaman” implies a personal transformation uniting animal, human, and divine, making a journey into another dimension for a specific purpose. Nuo means exorcistic rite. It means protection. Nuo means a masked, danced, exorcistic drama performed by a sorcerer. Chinese scholars adopted the term wu nuo to point out that their visual and ethnographic research was as varied and diverse as shamanism. This work is not restricted to official state performances and the literary record.

Wanzai County. Note the “four eyes” or double spirits of the mask,

above and below, and the appearance of the upper figure being

carried. From The Art of Chinese Ritual Masks, SMC Publishing, 1996

The wu nuo mask has been a key to understanding and connecting behavior and objects. Based on the 5,000-year-old Neolithic Liangzhu jade, the sorcerer mask has two parts: the upper shows the half-beast shaman, the lower shows the the protective deity guiding and transforming. It is as if the shaman is riding the protective spirit. There are other conspicuous features among the ancient nuo prototypes: huge eyes, immense noses, protruding teeth and fangs. Some today have remnant designs evoking archaic Liangzhu forms, and some contemporary metal Buddhist masks are nearly identical to Shang dynasty prototypes. Discoveries like these are stunning, exciting, and perhaps some are astonishing coincidences? But rather, it is more likely that wu nuo culture has never stopped being performed, shared, modified, adapted, whether taken underground or wrapped in religion and drama. There is something primal and perennial in these rites.

As with the practice of Indian mudra, or empowered hand movements, which appear to date to remote antiquity and never seem to have stopped being performed throughout the history of the world, continuing robustly today, so too perhaps wu nuo? Tracing wu nuo through cultural and ritual history is not unlike tracing the similarly very long-lived dance bugaku, now existing only in Japan. It’s possible. It’s viable. As the world’s knowledge repositories are made more available, connections between ancient phenomena appear. Art, language, literature, dance, ritual, religion—we know more about these things now.

assimilated performance history of what is now Japanese bugaku

and the very long assimilated performance histories of wu nuo rites.

Again, note how the higher spirit, the dragon, appears to be riding

the Ryo-o deity. Image courtesy of Tessshu-ji, Shizuoka

Just as the ballet choreographer George Balanchine stated: “If you have a man, a woman, and some music, you have a drama,” so too with nuoxi exorcism drama: if you have a sorcerer and a demon and a problem, you have a drama. Exorcism is dramatic by nature, and in Asia is something always performed masked and danced. Exorcistic performance exists at many levels, from a year-end agricultural rite, to a state-sponsored annual ritual, to a simple auspicious blessing. The history of nuo had an inflection point when non-sorcerers, such as government officials, actors, martial artists, and others conducted the rite, playing the role of the sorcerer. The sorcerer remained the central figure.

A Zhou dynasty (510–314 BCE) document, The Rites of Zhou, describes the official state sorcerer: “The golden four-eyed sorcerer [fangxiang], dressed in a black jacket and red skirt, covered with a bear skin, grasping a lance and brandishing a shield, conducts the seasonal Nuo rite, leading 100 slaves into houses and tombs to chase away pestilence, ghosts, and spirits.” This statement made more sense when 20th century archaeological digs in Liangzhu and Sanxingdui unearthed Neolithic jades and Shang bronzes of wu nuo masks and figures 3,000–5,000 years old. These discoveries unleashed the wu nuo craze, the nuoxi craze among scholars. This is not so unlike the craze that surrounded the discovery of King Tut in Egypt.

Baima Tibetan Village, Sichuan.

From The Art of Chinese Ritual Masks, SMC Publishing, 1996

In 1983, the Chinese government undertook a survey, province by province, of all the regional varieties of traditional theater. This was an ethnographic endeavor of a high order. One resulting product of this multi-year project was a lavishly illustrated scholarly book released in 1996: Chinese Ritual Masks. There’s nothing like it; 22 editors, four authors, and nearly 100 photographer-researchers from various disciplines. Who would imagine that such an extensive survey would reveal an ancient ritualistic cohesion among many types of people and customs?

Archeological discoveries about nuo culture were followed by a vast national research project in the mid-1980s, and an international publication of masks in the 1990s. This is enviable cultural studies research and output. There are other Chinese books of traditional masks, but untranslated and not so gorgeous. The scale of the research introduced the term nuo to broader use beyond state rituals officially called Nuo rites. Nuo came to be a new scholarly category defined by a sorcerer, exorcistic ceremony, dance, and mask. It is clear that the state Nuo were neither the source nor the demise of nuo, although the state rituals for hundreds of years established the ritual necessity and reverence, and adaptability of Nuo ceremonies, rites, and dramas.

Chinese dance scholarship is hard to find in English, so the publication of The Art of Chinese Ritual Masks, edited and compiled by Xue Ruolin with Chen Hongren and Yu Daxi, was momentous. Published by SMC Publishing in Taipei, the volume comes with a skillful translation, and indeed every caption in the extensive portfolio of mask photographs is translated, albeit with some typical Chinese renaming of cultural assets to provide a Chinese veneer on things that are not Chinese.

Chinese scholars knew of state-sponsored court Nuo performances, some quite elaborate, with more than 100 eunuchs participating as virgins. In other performances, the sorcerer danced with 12 animals (masked dancers), in another with 108 masked characters of various designs (this is very similar to Tantric Buddhist exorcistic danced ritual). In the court of the Han (202 BCE–220 CE), Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties, annual state Nuo ceremonies were fully recorded and described. Through the succession of dynasties, the rubrics for state Nuo barely changed. Again—despite there being plenty of records of official state Nuo performances from the Han, Sui, and Tang dynasties—the subject is barely known outside of Chinese academia. Any scholar of Chinese literature will be familiar with accounts of local masked drama, masked dance in warfare, and traveling opera using masks.

Tsomoriri, Ladakh, 2015. Photo by Joseph Houseal for Core of Culture

The Chinese academic posture toward cultural history is evolutionary. The outline of interpretation begins with Neolithic primitive society, which was totemic and centered on an animal totemic deity that was a source of life and livelihood, and connected to the tribal chief. This developed into deity belief, animating natural forces, deifying ancestors, life after death, and the idea that life resides in the skull. Half-beast-half-man shamans dancing in masks could connect to these planes of personal and communal psychic realty: divining for the tribal chief, bestowing protection to the tribe for fertility, hunting, and crops, protecting beings in the afterlife. Sorcerers jumping in graves and placing protective power in all directions was a standard ritual.

Part of the academic enthusiasm is connecting the great distance of time from the Liangzhu period 5,000 years ago to the Zhou dynasty, which preceded the Qin and the Han over 2,000 years ago. Scholarly work responded with visual, ritual, social, textual, and artistic evidence of a pervasive exorcistic culture that has not ended. The mask came to absorb the forces and intentions of the evolving rituals, linking the animal and the divine, the living and dead, the past and the present, while taking on local customs and metaphysical meaning.

Note the masked half-beast dancer wearing skins and horns.

There is some commonality of animal and divine transformation using masks

in East and West as far back in either civilization as one can seek evidence.

That elements of this belief and practice remain in the world today

says something about the human need for primal security.

Image from Core of Culture

Nuo continued as state ritual during successive dynasties through the high culture of great Tang. When the Mongols came to power in the Yuan (1271–1368), they ceased performing the Han cultural state Nuo, and basically exchanged it for Buddhist exorcistic ritual. Nuo never ceased, the type of Nuo changed, but a great state exorcistic ritual was performed every year. After 200 years, there was little transmission of the earlier state Nuo and it never revived after the Yuan. However, a multitude of local forms were thriving, blended with local customs, superstition, and drama. Buddhism and its rites continued and spread. Chinese opera is essentially exorcistic, and supernatural power abounds.

skin, a stag’s antlers and the body of a Buddhist Lama adorned with bone

ornaments, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 1967. Photo by Werner Forman.

Courtesy of the Werner Forman Archive

What’s the point of this glorious ethnography? To demonstrate, using sorcerers’ exorcistic dance masks, that a vast, archaic culture of exorcistic masked drama was widespread, wonderfully diverse, and identifiably the same thing. What has surprised researchers was just how alive wu nuo remains; how many examples of these practices are found in modern China and beyond. Masks are understood as part of dance performance; these are not separate studies as the ritual is essentially both. The dancer animates the mask; the mask transforms the dancer into animal or divine form, or both. The oldest appearance of “dance” as an ideogram in the Chinese language is in the most ancient Oracle Bone script. It is a picture of a shaman dancer holding branches. The oldest evidence of wu nuo culture are in the 5,000-year-old Liangzhu jade and the 3,000-year-old Shang dynasty bronze and gold masks. The contemporary evidence of wu nuo culture is strong, not least within the ceremonial dance practices of tantric Buddhism.

References

Xue, Ruolin, Chen Hongren and Yu Daxi. 1996. The Art of Chinese Ritual Masks. Taipei: SMC Publishing.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Dance as Knowledge, Part One

Dance as Knowledge, Part Three: Building a Research Team