Albert Museum. London, 2009. Photo by Jonathan Greet. From Core of Culture

Core of Culture (CoC) is an organization dedicated to safeguarding intangible world heritage and assisting the continuity of ancient dance traditions and embodied spiritual practices where they originate and beyond. CoC specializes in Himalayan cultures and Buddhist ritual arts. This work has been undertaken for 20 years by educating the public, practitioners, and scholars about disappearing cultural heritage. This is done collaboratively by specialized teams in remote field research, archival documentation, scholarly research, museum exhibition design, publishing, and fundraising. Since 2000, CoC’s work on Buddhist dance has appeared in 14 museums worldwide, and is held in five permanent collections. It features work by Gerard Houghton, Karma Tshering, Jonathan Greet, Thinles Dorje, Herbert Migdoll, and others.

It might seem unusual to some that dance is in museums, but in fact taking dance as museum subject matter has produced some blockbuster results, with exhibitions on the Ballet Russes at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Danser Sa Vie at the Pompidou Centre, Common Time: Merce Cunningham held concurrently at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and with The Dragon’s Gift, The Sacred Arts of Bhutan shown at six museums worldwide and being the first exhibition on Buddhist religious art that has included dance in the exhibition itself.

In honor of Core of Culture’s 20th anniversary this year, let’s take a look at some highlights from 20 years of museum exhibitions featuring Buddhist dance, each project with its own issues of presentation and content. The Scottish National Museum received a £42 million grant from the UK’s Lottery Fund to remount the entire Victorian wrought iron masterpiece. CoC was brought in to create a multimedia display that could feature examples from their 100-year-old complete collection of tantric Buddhist Cham costumes and masks. Three were selected: the Black Hat Sorcerer, the Horned Bull deity, Shinjey, and the dancer of the charnel ground, a skeleton.

Image courtesy of the National Museum of Scotland

The costumes and masks and implements were correctly assigned. Footage, both historical and contemporary, of each of the three ritual characters was shown, with a panoramic photo of a Cham ceremony, ritual implements, and interpretative text and photos.

The Dragon’s Gift, a touring exhibition of six museums, sought to reveal the correspondence and identity of ritual art and dance in Bhutanese Buddhist practice. To this end, a number of responses were created. A four-screen installation was devised, with different content on each screen, but unified and set to one single score of music. Critically, the four screens were edited and designed so that they appeared to circumambulate around the gallery or display, not only displaying movement but providing architectural motion, leading the observer’s eyes over both dance-based art and ritual dance itself. Each of the six museums installed this four-screen installation variously, creating different relationships between the art and the dance to be brought forward.

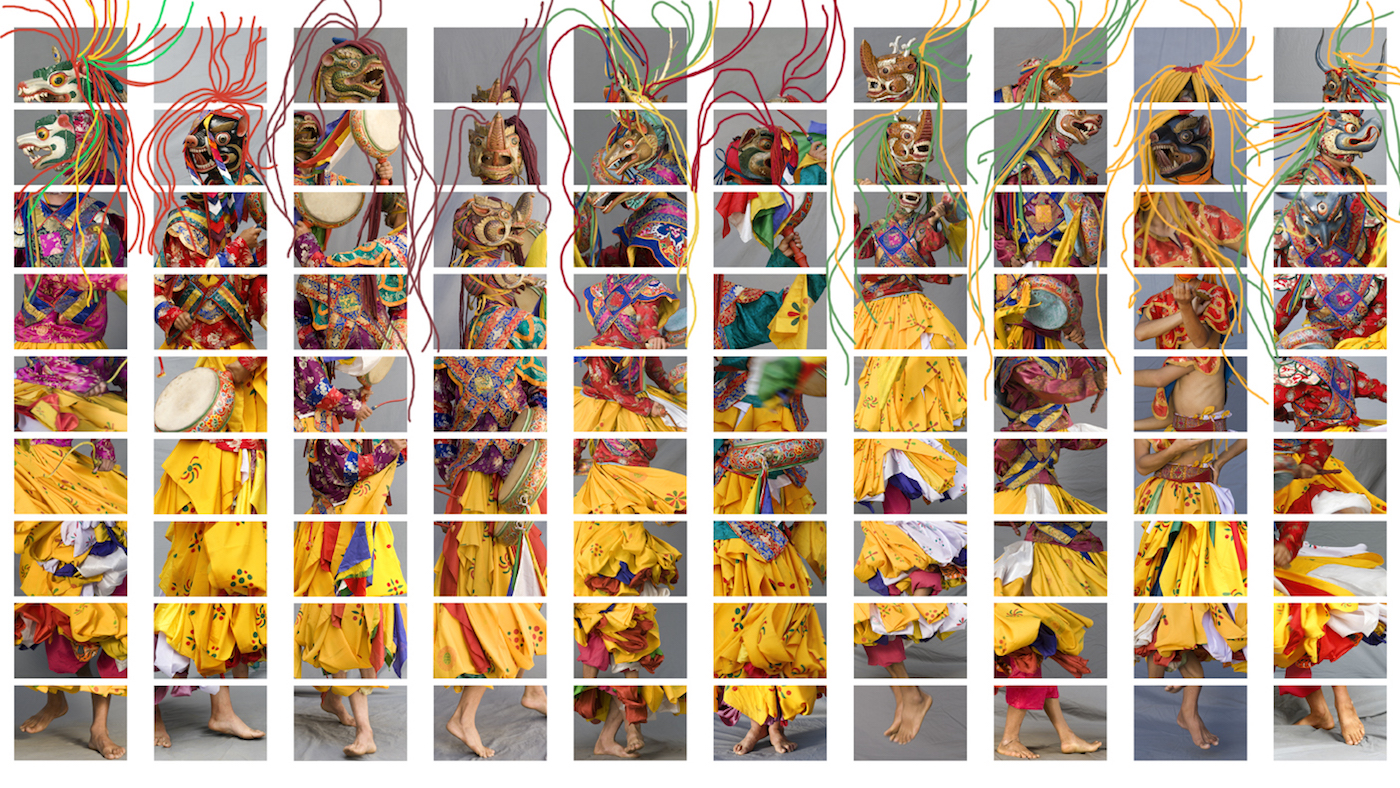

Another element of The Dragon’s Gift’s dance component was created by artist Herbert Migdoll, who photographed 67 different dancers individually. As the dancer moved and spun, Migdoll would shoot nine photos from head to feet, thereby photographing the dancing in time. He put these nine photos together as a kind of totem, representing a single dancer, and then he assembled a set of dancers to produce a new version of a Mani Wall, around which pilgrims circumambulate.

and Albert Museum. London, 2009. Photo by Jonathan Greet

In 2009, at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, The Robert H. N. Ho Foundation presented The Many Faces of Buddhism, uniting a gallery of Buddhist sculpture, a film festival, an array of avant-garde performance artists, and A Day of Rare Buddhist Dances, featuring ancient Buddhist dance traditions representing the full range of Buddhist schools of practice: Mahayana, Theravada, Vajrayana, and Zen. This was realized in Japanese Noh theater, Tibtan Buddhist nuns, a Vajracharya Nepalese priest, and a Sri Lankan folk clan. An authentic Noh stage was built at one end of the extravagant Raphael Room, and a Sri Lankan folk altar at the other end of the enormous barrel-ceilinged hall. The schools of Buddhism reflected in the sculpture were also reflected in the living performances of these ancient traditions, providing observers with a more holistic understanding and depiction of the allied arts in Buddhist expression.

London, 2009. Photo by Jonathan Greet

In 2019, and on display through October of 2020, at the Museo di Arte e Cultura Orientale in Arcidosso, Italy, Meditation in Motion, Footsteps to the Sublime took as its subject the phenomena of visionary dance in Buddhism and Dzogchen. It is a traditionally occurring experience of yogis, realized Buddhist practitioners, and saints, who learned dance during mystical yogic visions and turned these visions into actual dances. One of the highlights of the exhibition is a pre-figuring of dances seen in mystical visions. This was done thanks to Chogyal Namkhai Norbu’s revealed dances, and the extensive records and texts and diagrams he left to posterity. The body as spiritual laboratory, functioning in physical and metaphysical worlds, simultaneously acting in more than one dimension of existence, was innovatively presented, offering Westerner audiences some access to the sublime mystical visions of Buddhist adepts.

Museo di Arte e Cultura Orientale, 2019. From Core of Culture

See more