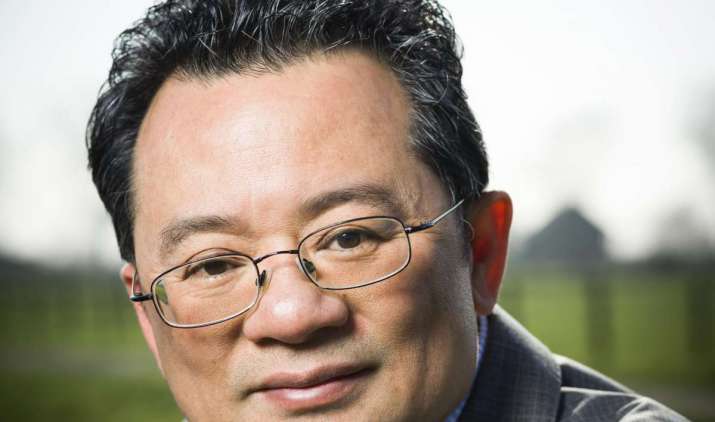

Cuong Lu, founder of the Mind Only School in the city of Gouda in the Netherlands, is a Buddhist teacher, writer, and scholar. Born in Nha Trang, Vietnam, in the midst of the Vietnam War, Lu and his family fled to the Netherlands when he was 11 years old. After majoring in Asian studies at the University of Leiden, Cuong Lu travelled to Thich Nhat Hanh’s Plum Village community in France, where he lived and practiced peace for 16 years. During his time there Lu was ordained as a monk under Thich Nhat Hanh’s guidance, and in 2000 he received recognition as a teacher in the Lieu Quan line of the Linji school of Zen Buddhism.

From 2011–17, Lu served as a prison chaplain in the Netherlands. His new book, The Buddha in Jail: Restoring Lives, Finding Hope and Freedom (OR Books 2019), offers insights into the lives of prisoners that will resonate with us all. This month, Buddhistdoor Global interviewed him on his life, work, and writing.

Buddhistdoor Global: In the introduction to The Buddha in Jail, you write: “I saw that I could help others overcome loneliness, as I had, and find meaning again in their lives.” Did your experiences growing up in a war zone have a bearing on your decision to serve others who are suffering?

Cuong Lu: I was born during the Vietnam war. My thinking and consciousness were programmed by the war, full of violence and fear. I didn’t notice that until I came to Holland, a peaceful country. In that peacefulness, I saw for the first time the suffering in me, brought with me from the war zone. Step by step, I have gone through that suffering and found peacefulness in me with Buddhist practice. I am a lucky person.

This experience has helped me to recognize the violence and fear in others. I want to help because I know how painful it is to have a war inside of you. It makes you feel lonely and hopeless. And I have also discovered that I can help. I can share with others my practice in a non-Buddhist way. Sometimes, I don’t even have to say something to help. When you are there without a war inside, other people can see that.

BDG: Can you tell our readers about your experiences as a monk in the Plum Village community and then as a prison chaplain?

CL: I was trained as a monk by Thich Nhat Hanh. That was a wonderful time. You are taken care of by your spiritual father. The connection between him and me was totally necessary for my spiritual growth. A teacher is much more than we think. A real teacher doesn’t transmit only his knowledge to you; he transmits himself to you. When you look into me, you see Thich Nhat Hanh.

As a prison chaplain, my role was taking care of the prisoners. These are people who have gone through a lot of suffering and they have caused suffering to many victims. I don’t agree with what they have done, causing suffering to others and to themselves. But I believe in their capacity to begin anew. As a prison chaplain, I give myself to each prisoner. I give them my deep trust as I have received it from my teacher Thich Nhat Hanh.

BDG: What was your creative process when writing The Buddha in Jail? In your introduction you explain that 70 men were in your care—how did you select which stories to tell?

CL: There are so many stories to tell. During the process of writing, I couldn’t choose. I allowed the stories to come to me. Each story contains in it the real suffering of life. It wants to be seen by all of us. When you look deeply, you see that I don’t only tell the stories of the prisoners. I tell our stories.

You can easily recognize your own suffering in my book, and that is very good. Once suffering is recognized, it can show you the way out of suffering. It contains in itself a secret: that is happiness.

BDG: Who can benefit from reading The Buddha in Jail?

CL: I don’t write this book for Buddhists. I don’t write this book for prisoners. I write this book for me and for you. Someone has called it “a deeply touching instruction manual on compassionate action in the world.” So, if you want to practice compassion for yourself or to help others, you can read this book. In this book, I have tried to touch the deepest aspect of Buddhism, and at the same time every spiritual practitioner can use this book as a guide to come back to their true home. When you touch your religion deep enough, you touch at the same time the roots of every religion.

BDG: Do you have to be a Buddhist to be a Buddha in jail?

CL: The historical Buddha wasn’t a Buddhist. He was a human being. He was someone who discovered his own value. And all of us can do that. We can all discover that we are Buddhas. In the prisons I worked, I helped Christians, Muslims, atheists . . . and just a few Buddhists. And they were all wonderful in their capacity to transform their suffering and begin their lives again as happy and free people.

BDG: You teach that happiness is the First Noble Truth. Can you explain this to our readers?

CL: The Buddha taught that suffering is the First Noble Truth (Skt: duhkha-satya). This is the core teaching of Buddhism. Suffering is noble, because it helps us to understand our own suffering and the suffering of others. It is the insight we need to have compassion in daily life. Once you can see the essence of your suffering, you are free. The Buddha didn’t see suffering as a problem, but as something you need to understand completely. Many people misunderstand it, they find that Buddhism is pessimistic.

From 2003, I taught happiness as the First Noble Truth (Skt: sukha-satya). It doesn’t mean you need to cling to happiness. You don’t have to look or cling to happiness, because it is there. And when you understand it deep enough, you will see that it is not different from suffering. Happiness and suffering, in their essence, are the same. Looking into suffering, you can see happiness. Because suffering is not an enemy of happiness. It helps us to recognize happiness we already have. Sometimes, in the midst of suffering.

BDG: What would you say to someone who believes prisoners should be punished for their actions?

CL: I support the law. I believe in the law. If you have committed a crime, you should be judged and punished by the law. But I have seen that punishing is not enough. We need to help too. First, we need to help the victims of the crimes. Second, we need to help those who have committed crimes. They need to understand what they have done, to others and also to themselves. Third, they need to receive support, to understand how to practice, in order to stop repeating their mistakes. They need to understand the way, going from suffering to happiness.

BDG: You write that when you first met Thich Nhat Hanh you were in awe of the way he embodied peace. You also write about the importance of embodying happiness and peace when serving prisoners. Why is this so transformative for people?

CL: It is not transformative. It just reminds people of what they already have: happiness. We forget that happiness is there within each of us. We don’t recognize happiness and we don’t appreciate it. We create war outside and inside of us. We divide our inner world into good and bad and we fight. A peaceful man is someone who has stopped the war within. That was the case of my teacher. He has stopped the war inside of him. Each of us has the capacity to stop the war in us. We don’t have to do anything to realize that. We just need to stop the fight. That’s all. Thich Nhat Hanh’s presence inspired me to do that. He reminds us that we are Buddhas. That is not a transformation. It is a confirmation, that we are all happy and free.

BDG: You write about society’s role in helping prisoners to “come home.” What does it mean to come home and how can we support prisoners to do so?

CL: Each of us does have a home to return to. That is our true root. It is our true identity. That is a place where there is no discrimination. In our true home, we accept each other. No matter who you are, I respect you. After practicing Buddhism for more than 20 years, I have found such a home, in me and in you. I want to bring everybody back to that true home, to your true self and to your true identity.

We can support the prisoners to come home when we know what true home is. We can help them to believe in true home when we are able to stop judging them. Respect the other like you respect yourself. When a prisoner is at home, he will be able to stop hurting himself, others, and society. Each prisoner is a part of society. Each prisoner is a member of our true home. Society needs to find ways to bring the prisoner back to a place where solidity and freedom are present.

List of upcoming public events (abbreviated)

Monday, 22 July, 7pm – The Buddha in Jail, presentation and book signing, Tibet House, 22 West 15th Street, New York City.

Thursday, 25 July, 8pm – Talk, Tender Shoot of Joy/Ordinary Dharma, Milwaukee.

Friday, 26 July, 7pm – Friends Meeting House, Madison, WI, http://snowflower.org

Saturday, 27 July – Daylong Retreat, Madison, WI, http://snowflower.org

Sunday, 28 July, 10am – Talk, Zen Life and Meditation Center, Oak Park, IL, (Chicago area), www.zlmc.org

Monday, 29 July, 6pm – The Buddha in Jail, presentation and book signing, Webster Groves Christian Church, 1320 W Lockwood Avenue, St. Louis, organized by the St. Louis Buddhist Council and Inside Dharma (a prison ministry).

Tuesday, 30 July, 6pm – Reading and signing, Book Passage, Ferry Building, San Francisco, CA.

Wednesday, 31 July, 8pm – Talk at Kannon Do Zen Meditation Center, Mountain View, CA (Silicon Valley), https://kannondo.org

Thursday, 1 August, 7pm – Reading and signing, Books, Inc., Berkeley, CA.

Friday, 1 August, 5:30pm – Dharma talk at Berkeley Zen Center, 1931 Russell St, http://berkeleyzencenter.org

References

Cuong Lu. 2018. The Buddha in Jail. New York and London: OR Books.