Traditionally, Buddhism has focused on the development of the inner mind’s enlightened qualities as a means to reduce suffering and conflict. This is because the tradition sees the three poisons (Skt: trivisha) of greed (raga), aversion (dvesha), and delusion (moha) to be at the root of all suffering. In order to attain any semblance of peace, the Buddhist practitioner must turn inward and cultivate the opposite qualities of wisdom, generosity, and loving-kindness. It naturally follows that the cultivation of these qualities will have a positive impact on society as a whole.

In recent times, Buddhism has become far more socially engaged, and Buddhist ideals have helped to inform a variety of approaches to conflict resolution (both directly and indirectly). In this article, I look at some of these approaches with the hope that they may provide some ideas about how humanity can move toward peace in these challenging times.

Being peace

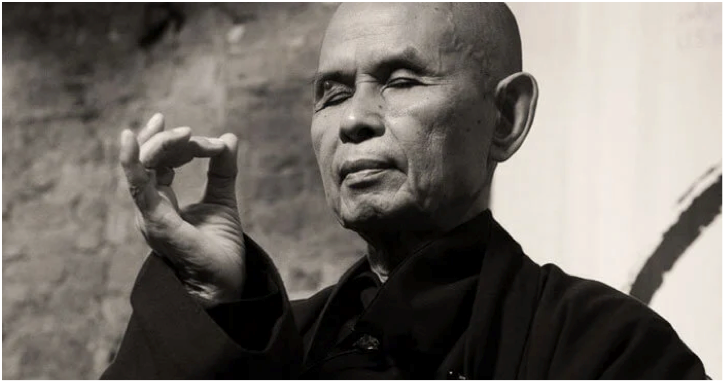

Vietnamese Buddhist teacher and author Thich Nhat Hanh was exiled from his homeland during the Vietnam War, and he has spent the decades since preaching and practicing “embodied peace” as a means to alleviate global suffering. In order to understand the significance of embodied peace, I turned to one of Hahn’s students, Buddhist teacher and writer Cuong Lu.

Cuong Lu was also born in Vietnam and fled the country as a young boy during the war. In his book The Buddha in Jail (2019), Lu recounts how, when he moved to the peaceful country of the Netherlands, he could not help but bring the war with him. Having only experienced life within the context of heightened and violent conflict, it took him a great many years of practice to develop a sense of inner peace and to trust the outside world. Fortunately, his experience of touching his deep suffering enabled him to awaken similar qualities in the hardened prisoners that he encountered working as a prison chaplain. The following is an expert from the book that beautifully captures the ripple effects of embodied peace:

Happiness is in each of us, but we don’t know it. Prisoners feel it right away; they just need an example. The people they met before—their parents, teachers and friends—weren’t happy. When I embodied happiness, they felt it. One day as I was walking past a row of cells, a man behind bars looked at me and said, “You see the light, right?” I laughed and said, “I’m happy.” He nodded, “I can see it. Very nice.”(Lu 2018, 31–32)

Throughout the book, Cuong outlines the positive effects that simply being (ie. being present, being at peace, being happy) can have on inmates, which in turn contributes to a more harmonious prison life.

Practices for cultivating embodied peace include: conscious breathing, kissing the Earth with our feet, mindful eating, sitting together, simply listening, and more.

Secular versions of “being peace”

While it may not immediately be apparent, Buddhism—and particularly the “mindfulness” component of the Buddhist practice—has had a significant impact on Western psychology. This means that people who do not identify specifically with Buddhism as a religion can still engage in practices that help cultivate inner peace. In the 1970s, Jon Kabat Zinn famously developed the mindfulness-based stress reduction and psychotherapy (MBSR) program, an eight-week course that focuses on mindfulness as a means to address depression, anxiety, and physical pain. The training module has seen significant success the world over and it regularly features in hospital and school curricula. MBSR is generally conducted in a group setting and includes practices such as meditation, body scans, and mindful yoga, as well as group therapy.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), on the other hand, resembles the more typical therapy session in that it usually takes place one-on-one, between the therapist and the patient. Similarly to cognitive-based therapy (CBT), which is widely practiced in the Western world, MBCT educates the practitioner about depression and the role that cognition plays within it. It encourages patients to recognize their thoughts and feelings just as they are, without becoming overly attached to or judgemental or reactive to them.

Nonviolent communication

The late psychologist Marshall B. Rosenberg came up with what he refers to as “a process of communication” that is rooted in attentiveness and compassion: “I have . . . identified a specific approach to communicating—both speaking and listening—that leads us to give from the heart, connecting us with ourselves and with each other in a way that allows our natural compassion to flourish. I call this approach Nonviolent Communication, using the term nonviolence as Ghandi used it—to refer to our natural state of compassion when violence has subsided from the heart.” (Rosenberg 2003, 2)

In a similar fashion to Buddhism, nonviolent communication (NVC) encourages both the listener and the speaker to observe things as they are—instead of evaluating or judging what the person is saying, one learns to listen from the heart. NVC also invites the listener/speaker to take ownership of their feelings and to find ways to express their needs. Founded on the principals of compassion, it serves as a valuable resource for communities facing violent conflicts the world over.

Mindful of race

American Buddhist teacher and author Ruth King carries out a training program across the US called Mindful of Race, which encourages participants to deeply investigate their relationship with racial bias and ethnic discrimination. King offers a variety of tools with which to address racial ignorance and distress. Among these are: guided sitting and walking meditations; RAIN (Recognize, Allow, Investigate, Nurture), a mindfulness-based practice that enables us to recognize our racial biases and distress; and Racial Affinity Groups (RAG), a space for people of the same ethnic background to come together in order to investigate and transform habits of harm.

As all the above practices indicate, there are diverse ways to reduce harm and bringing about peace. However, it is not easy and remains a long-term, even lifelong commitment. Whether it be learning new ways of communicating and relating to our thoughts, engaging in group discussions about race, or treating each step as though it were a kiss to the Earth, we can all take some measures to help reduce conflict in our hearts and, ultimately, the world.

References

Lu, Cuong. 2018. The Buddha in Jail: Restoring Lives, Finding Hope and Freedom. New York and London: OR Books.

Rosenberg, M. B. 2003. Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life. Encinitas: PuddleDancer Press.

King, Ruth. 2018. Mindful of Race: Transforming Racism from the Inside Out. Boulder: Sounds True.