Earlier this year, Buddhistdoor published the life story of Ani Zamba Chozom in eight weekly parts.* One of the first Westerners to be ordained as a Buddhist nun, Ani Zamba currently lives in Brazil, where her practical teachings, rooted in the simplicity of Dzogchen, are proving an inspiration to Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. Here, in three weekly parts,** is a sample of Ani’s teachings, in the form of a conversation.

Frances McDonald: How can people motivate themselves to get through the fear of not having reference points? Maybe we have an intellectual idea about it, and partly we realize the current situation isn’t satisfactory, but at least it’s familiar. We’re going into the unknown, and we ask, “Do I really want that? It sounds good, but perhaps this isn’t so bad after all—I can do something that makes me feel good!” How can we get through that?

Ani Zamba: Once you become familiar with releasing whatever is arising, without any preferences, you get so familiar with letting go that there’s no tendency to want to hold on to anything.

FM: So in the beginning maybe it becomes another habit. We create a different kind of habit.

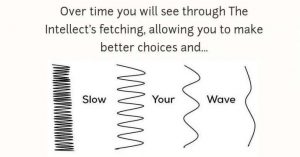

AZ: It becomes a habit until it becomes natural. Now we have the habit of holding on. We feel totally insecure because of changing conditions, which motivates us to try to hold on to something so we have some ground. But if we get more and more familiar with the movement as being something totally natural, there’s nothing to hold on to and we can relax and let go. Everything then becomes transparent—everything just opens out into its own spacious nature. It liberates itself of any solidity.

FM: Do you think discipline is the answer to creating this habit? Or do you think contemplating the four mind-changings [precious human rebirth; death and impermanence; karma; and the defects of samsara] is a way to motivate yourself? And how can you continue to motivate yourself to move through that fear? Often you delude yourself into thinking you’re doing it for “all sentient beings,” but that’s just jargon, in a way.

AZ: I think that’s an excellent question. The idea of all sentient beings is a psychological trick to bring us back to the idea of equal vision—we can never realize emptiness when we don’t have equal vision, so we need to become familiar with a way of seeing that goes beyond preferences and bias. Only when we have equal vision can we begin to see more easily how we are reifying every relationship in our life, because we’re not really having a relationship with anyone outside, we’re just having a relationship with ourselves! But we don’t see that because we really believe that whatever we perceive actually exists the way we think it does, and so we never see the emptiness. You can’t see the emptiness of any phenomenon until you go beyond mental fabrications, conditioning. You’re fooling yourself.

FM: But how can people get to the point where they really want to do that? We fall back into the habit of solidifying things time and time again. Tsoknyi Rinpoche says that Westerners make the mistake of thinking it’s enough just to get the point. Some people have been listening to these teachings for 20 years, and they still come and listen, but they seem to get stuck.

AZ: I think somehow we still have the attitude of wanting to be entertained. We don’t really apply the teachings to the way we see life, so then we don’t have the confidence to apply them. The teachings are tools, and it’s only through utilizing tools that you begin to understand how to use them and develop more confidence in using them. If you have the most sophisticated tool but you never take it out of the box, you’re never going to have the confidence to use it.

FM: Maybe people also get stuck because they still think samsara can work, and they don’t want to go through the hopelessness you can experience when you know it’s never going to work. Again, I remember Tsoknyi Rinpoche once saying, how on earth can you satisfy something that doesn’t exist, meaning the perceiver or the ego. But still you want to make it work . . . I think most people don’t want to even go to that point. Though maybe that’s where compassion really starts to manifest—life can no longer be about yourself.

AZ: With the familiarization of letting go, the fear doesn’t touch you. Whatever it is, as soon as you notice it to be anything, let it go—even the tension, even the fear, the joy, whatever is arising—as soon as you feel anything, let it go. The more you let go, the more you can rest. You don’t have to pick up anything, reject anything, change anything. What a relief! You can just be there, and within that being there, there’s that clarity that gives you the confidence to be there, and you can see very quickly when you’re not there. The problem that I see is that people want an instant result, so when they see that they’re still getting frustration and lots of tension, conflicts, and everything else, they kind of give up. Of course it does take discipline because we have to want to see—if we don’t value the idea of freedom, then what are we doing and why are we doing it? It’s virtually just to maintain our comfort zone, isn’t it? It’s not about freedom, it’s not about working with the cause of our confusion and suffering. We don’t want to get to the cause of it, we just want to put a patch on it so we don’t have to experience it so often and with such intensity.

FM: We just want to feel better.

AZ: So yes, I think study is helpful. Impermanence and change—oh my goodness, just keep looking at every aspect of change in your life—you can’t keep anything fixed and solid. There’s nothing that you can really hold on to because the phenomenal world is constantly changing. Alright! Now let’s relax more with this movement. Don’t pick up anything and make it into anything. Just let yourself become one with this movement, without trying to secure yourself all the time. I think the four seals [all compounded things are impermanent; all emotions are painful; all phenomena are empty; nirvana is beyond extremes] are so helpful if we really go into them and integrate the meaning into our perception more and more. The problem is that people don’t bring it back to the way they actually see their daily life situations. So then it’s either meditation or life—or study a frozen theory about things. You’re much freer in the direct perception, but we run back to the theory of trying to freeze it into an idea, and then we think we know and so we don’t look, because we think we know already.

FM: Do you think that’s always been the case? When these teachings were given in the past, people maybe didn’t have busy jobs and all of that.

AZ: I think we do have less time now—seemingly—with the world of cell phones and computers. All the time we’re just invaded by some kind of stimulus. We’re addicted to the speed of that stimulus, and it’s hard to actually disengage from the habit of interacting with whatever stimulus is going on in order to be able to see things more clearly. So then, not having something to listen to, look at, taste, smell, think about, that’s what’s frightening, isn’t it? When I don’t have that, then what do I do now, who am I? That’s how you confirm your existence, isn’t it? You must have an objective world in order to feel that you exist.

FM: Maybe in a way we’re fortunate to have all that because we can use it as a tool to bring us back to our nature—more than if we didn’t have that.

AZ: Definitely—if we use it. But we’re not using it. “Life is practice, practice is life,” that’s one of my main phrases. You don’t have to go to a special place, sit in a special position, you don’t need any of that, but you do need to work with whatever is arising. It’s not about forcing oneself to see something in a certain way—that’s completely fabricated, isn’t it? It’s just about relaxing into what is completely natural. At the moment that’s unfamiliar—immediately we have to hold onto something. We freeze space into what appears to us as the phenomenal world and we freeze space into what we consider to be “me,” so that this interaction of mind can perpetuate itself. The practice starts when you begin to investigate how you see, and if it really is as solid as you think it is. Relax, let go of all these things that you normally hold on to, and the phenomenal world becomes more and more transparent. And then, correspondingly, the perceiver of the phenomenal world becomes transparent. Thus these two apparent solid entities, like two ice cubes in a bowl of water, begin to melt, and as we do not maintain the tendencies to solidify this dualistic fixation, we liberate these illusory appearances back into their own nature.

*The Life Story of Ani Zamba Chozom: Part One – Journey to India

The Life Story of Ani Zamba Chozom: Part Two – Meeting Lama Yeshe

The Life Story of Ani Zamba Chozom: Part Three – Ordination, First Retreat, and First Teaching

The Life Story of Ani Zamba Chozom: Part Four – Finding the Nyingma Lineage

The Life Story of Ani Zamba Chozom: Part Five – Dzogchen and Meeting Her Teachers

The Life Story of Ani Zamba Chozom: Part Six – Thailand, Burma, and Korea

The Life Story of Ani Zamba Chozom: Part Seven – From Korea to the Philippines to Hong Kong

The Life Story of Ani Zamba Chozom: Part Eight – Brazil

**A Conversation with Ani Zamba, Part One: Looking at Things in Different Ways

A Conversation with Ani Zamba, Part Two: Benefiting Others