Image courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery and the artist

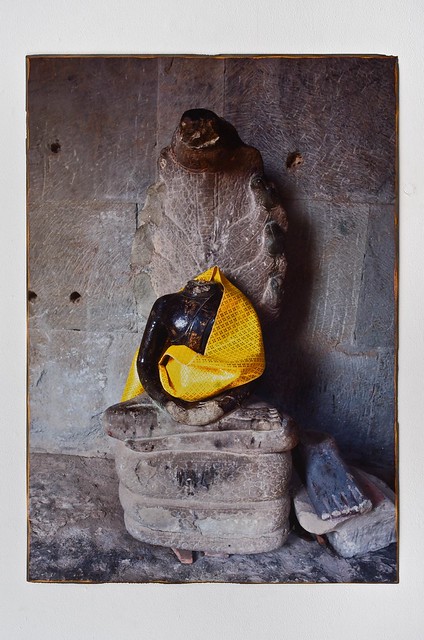

Any visitor to the Buddhist temples of Angkor and many other temples in Cambodia and Thailand will not fail to notice that many of the statues of the Buddha, either seated or standing, are missing their heads. A few of the heads can be found nearby, placed carefully on a wall or even embedded within tree roots, as with the famous head at Wat Mahathat in Ayutthaya, Thailand. More often, however, the heads are long gone, many knocked off and stolen by thieves (both local and foreign) and sold on the international antiques market. As the most artistically valued part of the Buddha statues, these heads have been so widely collected over the decades that bodiless Buddha heads are now quite commonplace in Western museums and private collections.

Severed Buddha heads and images of headless Buddhas are the subjects of several photographic series by Vietnamese/American photographer Dinh Q. Lê. For more than 30 years, his innovative and thought-provoking photographic and video works have explored physical, geographical, and spiritual disconnectedness and fragmentation. Among these, his headless Buddha images have been drawing attention to the wrecking and looting of Southeast Asia’s cultural heritage, while at the same time demonstrating that even these decapitated figures of the Buddha continue to possess considerable artistic and spiritual significance.

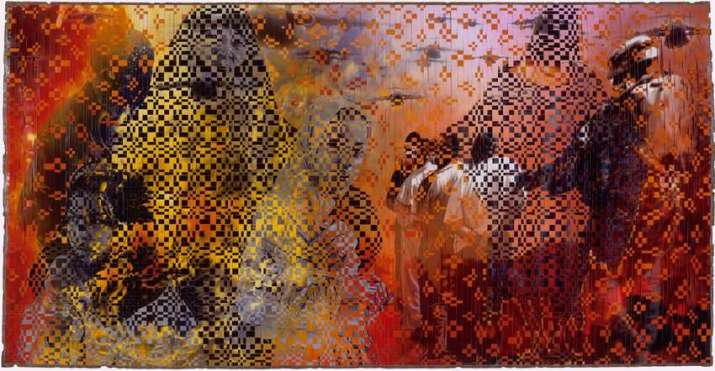

Dinh Q. Lê’s photography was born out of a desire to reconcile his two very different lives and cultures. Born in Vietnam in 1968, he immigrated with his family to Los Angeles in 1978 as a refugee of the war-torn region. He studied photography at the University of Southern California, Santa Barbara, and then obtained an MFA from the School of Visual Arts, New York. While still a student, he developed a technique of photo weaving that was inspired by the traditional Vietnamese art of bamboo mat weaving that he had learned from his aunt as a child in Vietnam. These photo montages typically weave together thinly cut strips of photographs from the Vietnam War—depictions of soldiers, aircraft, execution scenes—with more peaceful images of women, children, monks, Buddhas, and landscapes.

Image courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery and the artist

The result are images that appear broken down or pixelated, suggesting the fragmentation and incompleteness of Lê’s own identity, memory, and perhaps even of reality itself. At the same time, however, a new reality seems to emerge in the woven works—a reconciliation of the complex extremes of life, death, war, love, horror, and beauty, all intertwined into a single image. Iconic war scenes of children fleeing bombings and execution scenes are interwoven with more joyful, richly colored imagery or strips of linen tape to produce patterns that dilute the otherwise horrific images and transform them into something hauntingly beautiful and potentially healing.

Image courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery and the artist

In his photographs featuring headless Buddhas, we see a similar artistic restructuring and reexamining of reality. In the late 1990s, Lê moved to Ho Chi Minh City, where he not only set up an art studio but also began addressing Vietnam’s lost cultural heritage by amassing a collection of ceramics and Buddhist sculptures in an effort to preserve the past. In 1998, he began to focus his lens on damaged Buddhist statues, developing an exhibition titled Headless Buddha that traveled around the United States. The exhibition featured a number of woven photographs, but the most notable piece was a photograph of a headless stone Buddha seated in the lotus position and wrapped in a silk sash. It was mounted in a light box on the gallery wall, and facing it was a Buddha head on a pedestal positioned to look at the photograph, as if gazing at its long-lost body. By spotlighting the decapitated sculpture from a Buddhist temple, Lê not only draws attention to the destructive practice of damaging holy statues but also offers a sort of healing through an artistic recontextualization of the statue. Here, Lê not only highlights the sad truth that these sacred objects were destroyed to meet demand from art collectors, but he does so within the context of art museums, which now often house the stolen heads. By symbolically reuniting the Buddha and its head, though still feet apart, he poses important questions about the value of such sacred figures, not just in the artistic—and therefore financial—but also in the spiritual realm.

43-1/8” x 30-3/4” each. Image courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery and the artist

Lê continued to feature the headless Buddhas in another photo series depicting violated statues from the Buddhist temples of Angkor in Cambodia. A series of 15 digital prints entitled The Headless Buddhas of Angkor, were part of Lê’s Remnants, Ruins, Civilization, and Empire show at Shoshana Wayne Gallery in Santa Monica, California, in 2012. Here, each frame contains a different figure of the Buddha photographed in a temple context, seated on a stone pedestal, against a wall. Each Buddha figure is missing its head and sometimes even its torso, but the statues are clearly still revered by local Buddhist, as demonstrated by the colorful silk sashes that have been lovingly draped over their shoulders, apparently for New Year celebrations. Even headless, the statues remain the focus of worship for local Buddhists. While in artistic terms, the head of a sculpted figure may be the most highly prized element, the spiritual importance of a Buddhist statue lies less in the wholeness of its physical form than in the ideals it represents.