Right Understanding and Right Intention are difficult to grasp; but the factor that follows—Right Speech—is easier to comprehend because it is less abstract and has to do with the direct practice of right intentions in everyday communication.

The Buddha taught us how to purify ourselves through being mindful of our actions as a means of progressing toward higher understanding. The purpose of practical ethics is ultimate purification. It is no coincidence that Bhikkhu Nanamoli’s translation of the classic manual of Buddhist doctrine and meditation, the Visuddhi Magga is called The Path of Purification. (Nanamoli 1975)

A monk once asked the Buddha for a brief summary of his teachings, and he said:

“First, establish yourself in the starting point of wholesome states, that is, in purified moral discipline and in Right View. Then, when your moral discipline is purified and your view straight, you should practice the four foundations of mindfulness.” (Samyutta Nikaya XLVII.3).

In other words, follow the Noble Eightfold Path, being sure you purify yourself through the performance of good kamma as a preparation for deeper insight. The problem is that if one cannot develop moral purity, one will encounter the greatest of difficulty in going forward.

In The Word of the Buddha, Venerable Nyanatiloka Mahathera translates the teaching of the Buddha (from the Anguttara Nikaya X.176) that one must abstain from lying and tell the truth, be reliable and worthy of confidence. Never deceive. Always tell what one knows and admit when one knows nothing. One should tell what one has seen and what one has not seen. One should never knowingly speak a lie for one’s own advantage, for the advantage of others, or for any advantage whatsoever. (Nyanatiloka 48, 1967)

This was the Buddha’s first statement on the subject of speech. Condensed into one short maxim, it means “abstain from false speech.” Here “abstention” implies replacing unwholesome kamma with wholesome kamma. Speech can provide wisdom, heal division, and create peace, but, falsely used, it can break lives, create enemies, and start wars. The law of opposites also works where speech is concerned.

One should never have the intention to deceive or to lie because of motives of greed or hatred. Never delude others for any reason, not even when exaggerating, joking, or jesting, because deception can lead to ill effects and cause harm. Lying corrupts society. Lies lead to more lies and affect one’s credibility. Lies lock one in a cage of falsehood, creating a corrupt world from which it is almost impossible to escape. (Bodhi 51, 1984)

The Buddha said that when you lie, you lose merit and go backwards rather than forwards. He illustrated the point, talking to his son and disciple Rahula:

Taking a bowl with a little bit of water in it and turning it upside down, he said,

“Do you see how the water has been discarded? In the same way one who tells a deliberate lie discards whatever spiritual achievement he has made. In the same way he turns his spiritual achievements upside down and becomes incapable of progress.” (Majjhima Nikaya 61)

The second statement the Buddha made was that one should abstain from slanderous speech. In other words, one should not repeat negative things one has heard about others: one should not repeat things that cause dissension. Instead, one should use speech to unite those who are divided, create agreement, harmony, and good will instead of disagreement.

One should abstain from speech motivated by cruel intentions or by resentment—speech that tears down another’s image, questions his virtue or success, or is intended to hurt others by getting ahead of them, or to hurt them for the sake of perverse satisfaction. The root of slander is hate, and hate is one of the most unwholesome forms of kamma—a pitfall very much to be avoided.

“The opposite of slander,” as the Buddha indicates, “is speech that promotes friendship and harmony. Such speech originates from a mind of loving-kindness and sympathy. It wins the trust and affection of others.” (Bodhi 54–55, 1984) When you feel like saying something slanderous about your neighbor, catch yourself and turn that impulse into loving-kindness. More good will come of it.

The third statement the Buddha made about right speech was that one should abstain from harsh speech, uttered in anger and intended to cause pain. Instead, one should use speech that is gentle, soothing to the ear, loving and readily reaches the heart—using speech that is courteous, friendly, and agreeable.

One should abstain from motives that provoke language that is angry or abusive, reproving, bitter, insulting, hurtful, offensive, demeaning, sarcastic, or ironic with intent to injure. There is no good reason for such language, and the main argument against it is that it arises out of anger and aversion. It is an impulsive action lacking deliberation that can lead to destructive consequences for oneself and others. The impulse has to be restrained to avoid the harm it can do.

The opposite of anger is patience. The antidote to anger is tolerance for the shortcomings of other’s criticisms, comments, and actions. One should learn to tolerate verbal abuse without the need to retaliate. (Bodhi 55, 1984)

The Buddha once gave a remarkable example:

“Even, o monks should robbers and murders saw through your limbs and joints, whoever should give way to anger thereat would not be following my advice. For thus ought you to train yourselves: ‘Undisturbed shall our mind remain, with heart full of love, and free from hidden malice; and that person shall we penetrate with loving-thoughts, wide, deep, boundless, freed from anger and hatred.’” (Majjhima Nikaya 21)

The fourth statement the Buddha made was to abstain from idle chatter. In other words, to avoid frivolous speech and pointless talk that has no depth. Instead, one should speak appropriately at the right moment in accordance with the facts, saying what is useful, speaking of subjects like the Dhamma and the discipline.

One should abstain from talking and listening to chatter that is shallow and stirs up defilements and restless thoughts, which can lead one astray. One should abstain from any sort of loose talk or valueless patter that leaves the mind vacant and sterile. This is especially true of frivolous entertainments that block development on a higher, spiritual, aesthetic, contemplative level.

The opposite of idle chatter is to make every word have meaning, so that speech becomes like a treasure, uttered appropriately and at the right moment, accompanied by moderation, reason, and good sense, inspiring listeners in matters of good conduct and the pursuit of the path. Another thing to remember is that while speech has its place, meditation leaves the limits of speech behind. Mental calm is the opposite of restless chatter.

Thus ends what the Buddha said about Right Speech.

References

Bodhi, Bhikkhu. 1984. The Noble Eightfold Path: The Way to the End of Suffering. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.

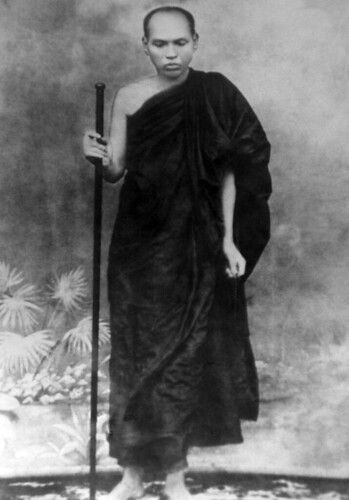

Ledi Sayadaw. 1977. The Noble Eightfold Path and its Factors Explained. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.

Nanamoli, Bhikkhu. 1975. The Path of Purification (Visuddhi Magga). Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.

Nyanatiloka, Mahathera. 1967. The Word of the Buddha. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.