From wikipedia.org

In the dictionary, nihilism is defined as the rejection of all religious and moral principles, in the belief that life is meaningless. It’s a philosophy that first became popular in the mid 1800s, however it didn’t become widespread until Russia’s communist revolution, which took place between 1917 and 1923. During this time nihilist philosophy was used to justify the destruction of old philosophies and traditions that had been used to oppress the proletariat.

In place of these traditional modes of thought, revolutionaries were encouraged to place their faith in science and the phenomenal world. This is expressed in Ivan Turgenev’s novel Fathers and Sons (1862), when Yevgeny Bazarov states: “What’s important is twice two is four and all the rest’s nonsense.”

Since these immortal words were written, nihilist philosophy has spread to every corner of the globe, permeating music, literature, and popular cartoons, such as Rick and Morty. And this isn’t a bad thing, per se. It’s important that we ask questions and challenge the normal way of doing things from time to time.

It was this type of disdain for tradition and social norms that allowed American women the right to vote in 1920 and the passage of the US Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made it illegal to discriminate against people based on race, color, religion, sex, or nation of origin. Clearly, “this is how we’ve always done it” is a way of thinking that can lead to great harm. And nihilism allows for the destruction of traditions that no longer serve us. However, there is a dark side to this philosophy.

If everything is meaningless and the only thing that matters is “twice two is four,” then there is no room for sanctity in life; no reason for compassion beyond the immediate, material needs of the moment. Thus, the same line of thinking that helps us fight the system in the name of social justice also allows us to hurt our fellow humans in the name of meaninglessness. If nothing matters, what’s the harm?

It’s this latter form of nihilistic thought that has weaseled its way into Western Dharma centers. It largely comes from a misunderstanding of the Buddhist teaching of sunyata (Skt: emptiness). As a concept, sunyata means that everything in existence is empty of a separate, permanently abiding existence. In other words, the phenomenal world is an illusion.

If we look at a table, for example, whether the table is “good” or “bad” has little to do with the physical object in front of us, and everything to do with our own concepts surrounding it. We cannot touch goodness in the same way that we can touch the table, thus it’s illusory.

However, this doesn’t mean that the table has a separate, permanently abiding self. Indeed, the table is made up of an aggregate of wood and metal. And if we examine it more closely, we find molecules, then atoms, then light waves, then nothing at all. The table, much like our thoughts, isn’t real.

In Buddhism, it’s common to use contemplations like this to break our attachments to material things. When we understand that cars, money, status, and so on, are meaningless at their core, we don’t feel so concerned when they leave us. This is in keeping with nihilist thought. Indeed, it leads to inner peace.

The problem comes, however, when we apply this same mode of thinking to people. If words are inherently meaningless, for example, one might jump to the conclusion that they can’t be harmful. After all, how can something hurt us if it doesn’t exist.

This line of thinking crops up in online forums, where harsh words are frequently used and if someone complains, they are accused of being too attached to social norms, too unawakened to see the empty nature of their own hurt feelings.

Furthermore, if the concept of race is an illusion, then racism cannot exist. If the concept of sex is an illusion, then sexual abuse cannot exist. If the concept of sexual orientation is an illusion, then homophobia cannot exist.

Thus, the teaching of sunyata is blended with nihilism to nullify the lived experiences of people who are harmed. The implication is that if they practice more, the feelings of hurt will go away, and the perpetrators of harmful acts are innocent of wrongdoing.

This line of thinking is in keeping with a nihilistic worldview, but it doesn’t align with a Buddhist worldview.

Because emptiness is only half of the equation in Buddhism. The other half is compassion; a compassion born of the fact that this world is an illusion, but we still need to live in it. It’s a compassion that says life is free of inherent meaning, so we’ll give it meaning of our own.

It’s a compassion that responds to nihilism’s “everything is meaningless” by saying “everything is Buddha.”

We choose to believe that everything in this empty world is precious and worthy of care. Thus, race is an illusion, but we still fight against racism. Sex is an illusion, but we prevent sexual abuse, and sexual orientation is an illusion, but we make the LGBTQ+ community feel welcome in our sanghas.

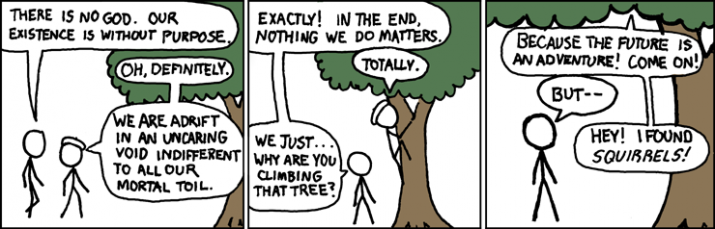

In this way, nihilism and Buddhism have similar starting points in the belief that life is free of inherent meaning, that tradition and social norms are not sacred cows that must be preserved at all costs. But where nihilism suggests that everything outside of the material world is useless. Buddhism reminds us that just because something isn’t real that doesn’t stop it from feeling real.

So we must treat everything in life as something sacred, building traditions and social norms that improve the lives of every Buddha in the world.

Namu Amida Butsu.

Sensei Alex Kakuyo is a Buddhist teacher and breathwork facilitator. A former marine, he served in both Iraq and Afghanistan before finding the Dharma through a series of happy accidents. Sensei Alex holds a BA in philosophy from Wabash College and his life’s work is helping students to bridge the gap between the finite and the infinite. Using movement, meditation, and gratitude practices, he helps them find inner peace in every moment. Sensei Alex is the author of Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life (independently published 2020). His book and other writings can be found on his website: The Same Old Zen.

“Buddhism reminds us that just because something isn’t real that doesn’t stop it from feeling real.”

So if God doesn’t exist, we should construct It in our imaginations?

If the human soul doesn’t exist, we should enact it in the world anyway, for the sake of its beauty?