Fujian Science and Technology Publishing House, 1990

Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism have mutually informed each other for well over a millennium. Practices associated with Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, such as meditation, fasting, reading sacred texts, honoring ancestors, and maintaining the body with exercise, are integrated into the cultivated practices of martial arts such as Shaolin gongfu, performing arts such as Japanese Noh theater, and fine arts such as painting and calligraphy. The 20th century witnessed the publication of many “secret” texts. I can hear my late editor in New York telling me: “If you know it . . . it can’t be that big a secret?” The matter of secrets, held and revealed, closed and open, is fundamental to transmitted movement practices.

The collected secret teachings of 14th century Noh theater founder Zeami, published as On the Art of Noh Drama, The Major Treatises of Zeami (Princeton University Press 1984), were not compiled until the 20th century. These writing are, in some ways, open secrets because without the knowledge of how to perform Noh, the application of the teachings is unfathomable. Zeami wrote that a real secret was something that could not be understood, even by a rival Noh actor. They might be moved by the effect, yet not know how it was accomplished. Zeami cites sophisticated passages of Buddhist texts to advise Noh performers, abstruse and lofty. Zeami was very well educated in Zen Buddhism by the Shogun’s court and advisors, and lived his life much as a Buddhist priest would have. It was customary in his time for leaders to “take the tonsure;” to retire and become monks; for women to retire and become nuns.

Zeami essentially advises Noh actors to live according to monastic precepts: no liquor, no profligate behavior, and a moderate diet, honoring parents, shogun, patron, ancestors. He advised them to read classical poetry, study Buddhist scripture, practice meditation, and be models of modesty and service. This was practical advice because it prepared the actor to actualize meditative and contemplative states in performance, based on training in them as a way of life. A way of life: Zeami provided Noh actors with a code for living; to be a Noh actor was to adopt a way of life, a manner of living. So, too, the martial artist and the monk.

Fujian Science and Technology Publishing House, 1990.

Here is an example of Zeami’s advice on how to create novelty, surprise, freshness onstage. Without knowing poetry and Buddhism, it would be difficult to comprehend. “Flower” (hana) is the essence of Noh. Zeami cites an ancient anonymous poem in a secret teaching called Disciplines for Joy. This work is a product of Zen culture, a pure expression of Buddhist aesthetics:

Break open the cherry tree

And look at it.

There are no flowers,

They bloomed

In the Spring Sky

The 20th century also saw the publication of a proliferation of martial arts training manuals and ancient treatises never before circulated widely. These texts are practical rules of applied Daoist, Confucian, and Buddhist principles. Now there are any number of books of martial arts secrets, among them Tai Chi Classics, translated by Waysun Chao, which presents three authentic pre-modern texts on the inner meaning of the movements of tai chi, as well as four short texts, The Sixteen Steps of Transferring Power, The Four Secret Procedures for Transferring Power, The Five Virtues of Tai Chi, and The Eight Truths About Tai Chi. Author and tai chi master Waysun Chao added drawings throughout the texts, providing thorough examples of the aphorisms applied—a kind of universal translation or realization of the text.

There are not so many attempts to put tai chi teachings into words, and the effort to translate requires knowledge of archaic Chinese, coded symbolic systems used by martial artists, complicated concepts coupled with technical terms and poetic sentence structure. Tai Chi Classics is a great contribution to knowledge. Please enjoy some of the 22 Key Points to Observe in Tai Chi Practice:

2. The eyes should be focused and concentrate on the direction in which the chi flows.

7. The coccyx should be pulled forward and upward with the mind.

11. Clearly separate the substantial from the insubstantial.

12. Each part of the body should be connected to every other part.

13. The internal and external should combine together; breathing should be natural.

21. Discover calm within action and action within calm.

Fujian Science and Technology Publishing House, 1990.

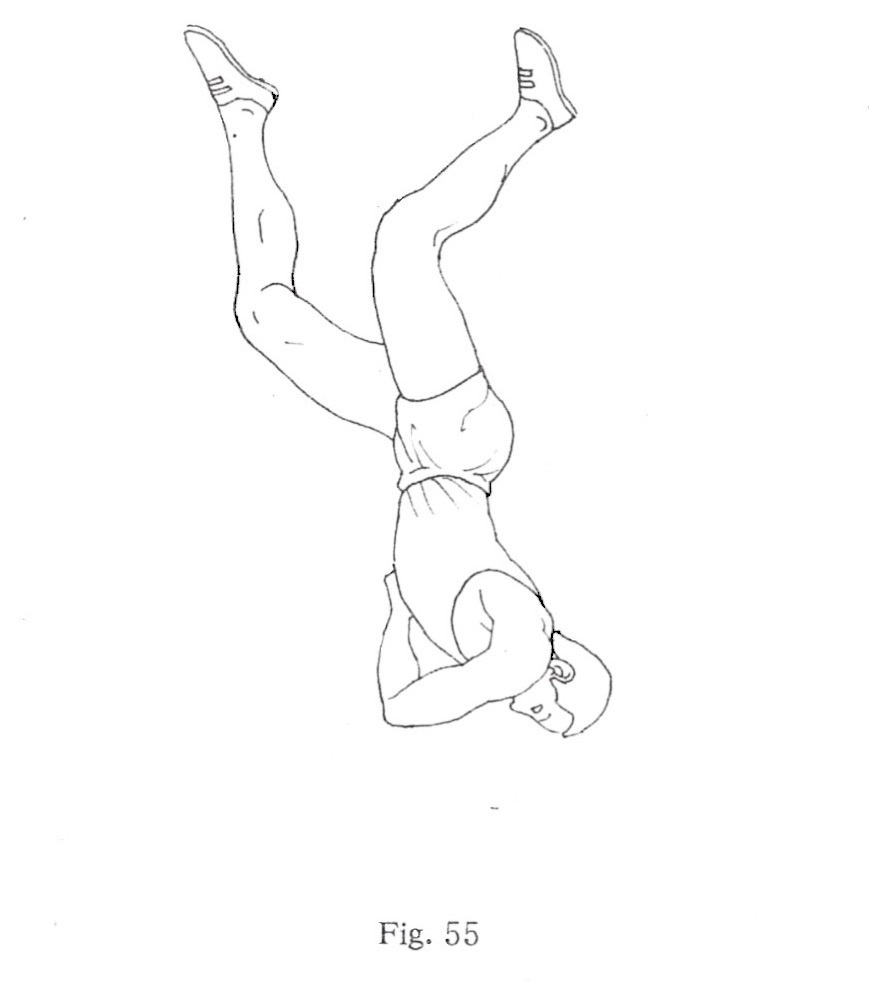

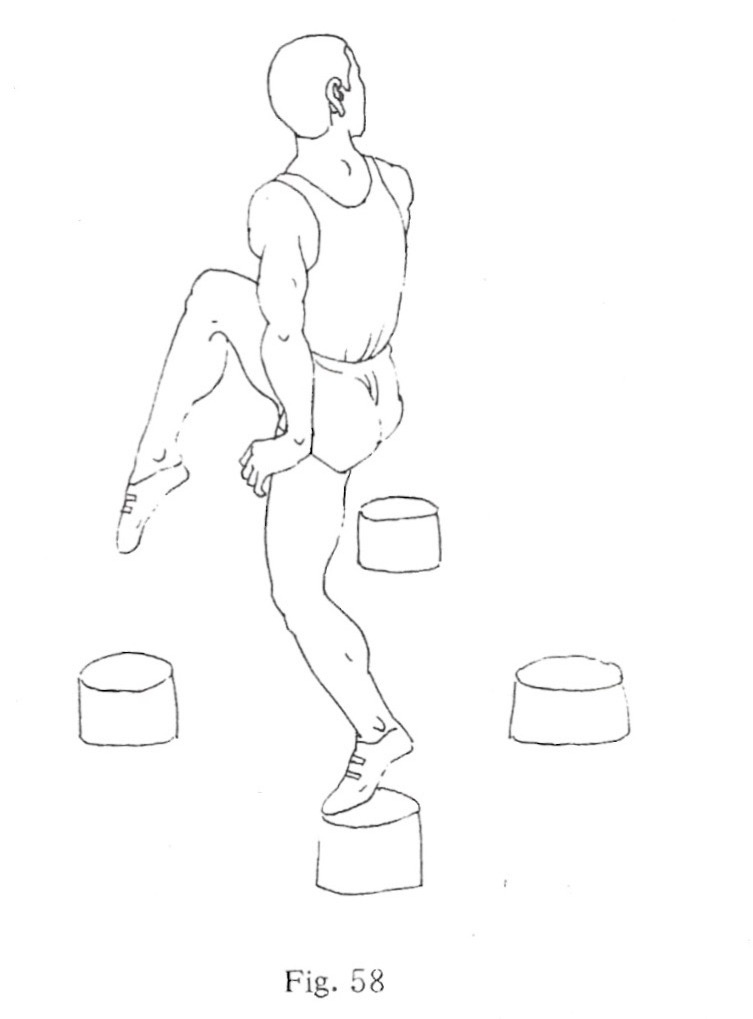

These maxims read like a code of personal cultivation, akin to and including meditation, religious observance, and virtuous modesty. Other books of martial secrets come out swinging: 72 Consummate Arts Secrets of the Shaolin Temple (Fujian Science and Technology Publishing House 1990). The ardent and humble translator Rou Gong was engaged by text compiler Wu Jiaming, who realized that there was virtually nothing authentic in English about Shaolin training. He aspired to remedy this by translating a fundamental Shaolin manual. An illustrative drawing accompanies each of the 72 secrets, which are discreet movement forms, together producing a comprehensive foundation of mental and physical technique. The present article is illustrated with five of these wonderful line drawings, not wholly unlike those in the 17th century ballet manuals by Carlo Blasis, who used line drawings in a similar way.

The Boxing Proverb is an old martial arts poem that introduces the 72 secrets extolling Shaolin Wushu, martial arts, and personal cultivation. Please enjoy this extract:

Inside the wushu bag, 72 skills lie

Which are well-hidden exclusive Shaolin Arts

So preciously implied.

Eighteen famous boxing forms give the reason why

And eighteen weapons here are demonstrated to tryAll fantastic ways of seizing, under a gentle breath,

Ease and the firm.

With the Buddhists blood, writing the works was thus compiled

Under the heavens with bloody training where only heroes vie.

No pains, no gains, the universal truth runs right.

More scholarly in a Western sense is the wonderful set of translated martial arts teachings, Budo Secrets, Teachings of the Martial Arts Masters by John Stevens (Shambala 2001). Stevens offers a bounty of 20 different source text teachings. Some are philosophical explanations; many are numbered sets of rules and codes. Some are expanded rules and codes. Many use calligraphy (not a drawing of human movement) to exemplify the martial principle being explained.

Fujian Science and Technology Publishing House, 1990.

Concluding this short look at codes of conduct in Buddhist-inspired martial and performing arts, is a text, The Nine Views, which was used as primary meditation training for samurai, whom, it must be remembered, dealt with death on a regular basis. Transcendence was not something far off. Honor and loyalty led the samurai virtues. Remarkably, the text was transposed into a Noh treatise by Zeami called Nine Stages, which I discussed in this journal earlier.* This Zen meditation training for samurai is known as The Nine Views. They are presented here without explanation or historical commentary. It is clear that this text was intended for warrior practitioners of Zen who would have access to a teacher within any number of transmitted lineages: familial, monastic, martial and artistic.

The Nine Views

A Meditation practice for Samurai

1. Observe the fundamental rules

2. Breathe from the belly

3. Soothe the spirit

4. Fulfillment

5. Natural wisdom

6. Liberation

7. True void

8. Marvelous function

9. Perfection, emptiness

Purity of heart and a free-flowing spirit are essential elements of martial arts and performing arts that rely on Daoist, Confucian, and Buddhist ethics. These dynamics of self-respect and principles of mental power unite with physical application, composure, and etiquette. Breathe from the belly. Like a Buddha. Words to live by.

Fujian Science and Technology Publishing House, 1990.

* Rarified, Recondite, and Abstruse: Zeami’s Nine Stages (Buddhistdoor Global)

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Buddhism and the Martial Arts: A Conversation with Scott Park Phillips

Immortality and Invincibility, Part One: The 108 Luohan System

Body and Mind in Chinese Martial Arts: A Conversation with Xu Xiangdong

Kung-fu and the Path of Integration with Sifu Keith Martin-Smith

World Peace! Thumbs Up! Some Martial Aspects of Buddhist Dance

Great article Joseph, thank you