In Buddhism, a Pure Land is a place of infinite bliss that provides support in our journey to enlightenment. The most famous Pure Land is the one created by Amida, the Buddha of Infinite Light. He started life as a monk named Dharmakara, but through the power of his practice, which lasted over countless kalpas, he attained miraculous powers and used them to help all sentient beings.

This is embodied in the primal vow of Amida Buddha, in which he states:

If, when I attain Buddhahood, sentient beings in the lands of the ten directions who sincerely and joyfully entrust themselves to me, desire to be born in my land, and think of me, even ten times, should not be born there, may I not attain perfect Enlightenment. (Inagaki and Stewart)

Thus, anyone who chants the name of Amida (Namu Amida Butsu) is guaranteed rebirth in his Land of Bliss after they die. However, this isn’t the only Pure Land that’s available to us. In Mahayana Buddhism there are an infinite number of buddhas and each of them is responsible for a pure land that differs based on their karma.

For example, the Tathagata of Wonderful Fragrances has a land where beings realize enlightenment by eating good food and enjoying lovely smells. And the Jewel Accumulation Buddha’s land is so ornately decorated that simply looking around cleanses us of defilements!

That being said, we don’t need to travel to another world to find a Pure Land. In the Vimalakirti Sutra, Shakyamuni Buddha states that this defiled saha world in which we live is also a Pure Land. Furthermore, he reminds us that his world is just as beautiful as anything we might experience in the lands of the Jewel Accumulation Buddha or the Tathagata of Wonderful Fragrances.

However, we must purify our minds in order to see the beauty that exists all around us. One can understand this by imagining that they are in a room with no doors and a single, dirty window that leads to the outside. It might be beautiful outside, with lots of sunshine and an endless blue sky, but the person in the room will never see it without cleaning the window.

In this example, the beautiful day is the pure nature of our world, the window is our mind, and the dirt that covers it represents the three poisons of greed, anger, and ignorance.

Of course, we don’t fault windows for collecting dust; that’s just part of what it means to be a window. Similarly, we don’t fault our minds for being impure, that’s just part of living in samsara. But we clean windows in order that we can see the sunshine. And as Buddhists, we clean our minds so that we can see the Pure Land.

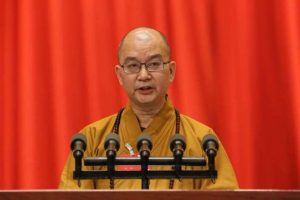

I experienced this firsthand during a silent meditation retreat that I did with Venerable Shih Ying-Fa, a Chan Buddhist monk and the abbot of CloudWater Zendo. During the retreat, we were instructed to always remain silent and to keep our eyes cast downward in order to not make eye contact with the other practitioners. Use of smartphones and laptops was not allowed.

That might sound strange to Western ears, but it was necessary during retreat. We must put down the toys and distractions of daily life—gossip, social media, political news, etc.—to turn our attention inward.

We engaged in the traditional Buddhist practices of chanting, prostrating, seated meditation, and walking meditation for three days, and it was during a period of walking meditation that I experienced a shift. It was cold outside and I was feeling grumpy as we traipsed through the dead autumn leaves. But I continued to walk and focus on my breathing as we’d been instructed. Then I stepped on a twig, and the world changed into high definition.

I’d barely noticed the trees before, but now I saw that each of them had five hues of brown in their trunks. The dead leaves that covered the ground were like jewels, glowing with shades of red and orange that I’d never noticed before. And each of them possessed unique patterns and textures. The world had changed from being cold, gray, and muted to being wonderful and alive!

I enjoyed the experience but it was also overwhelming, so I was both relieved and a little sad when we returned to the cabin we were using for the retreat and everything went back to being dull and gray. It remained that way when we did the next round of walking meditation.

As I looked around the trees were just trees and there wasn’t anything special about the dead leaves. But when I picked up a leaf and took a closer look, I saw something spectacular. The colors and textures that I’d seen earlier were still there. I just needed to look more closely to see them. The world was just as beautiful as it had been earlier in the day, I just needed to remember to look.

This is the power of Buddhist practice. It helps us to clean the window of our mind, so that we can see the purity of the world around us. The traditional practices of chanting, prostrating, seated meditation, and walking meditation remove layers of greed, anger, and ignorance from our psyches so that the true nature of our world becomes clear.

And as we see our environment more clearly, we notice the beauty of things we once took for granted. Instead of complaining about a cold winter day, we express gratitude for our warm coat. Instead of feeling bitter when our favorite foods aren’t available, we express joy because we have other foods to choose from. And we do something we never did before.

We notice the countless ways that sentient beings help and support us in daily life. And the Pure Land of this world is revealed with every step we take.

Namu Amida Butsu

References

Inagaki, Hisao and Harold Stewart (trans.). 2003. “The Sutra on the Buddha of Infinite Light.” In The three Pure Land sutras. Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.