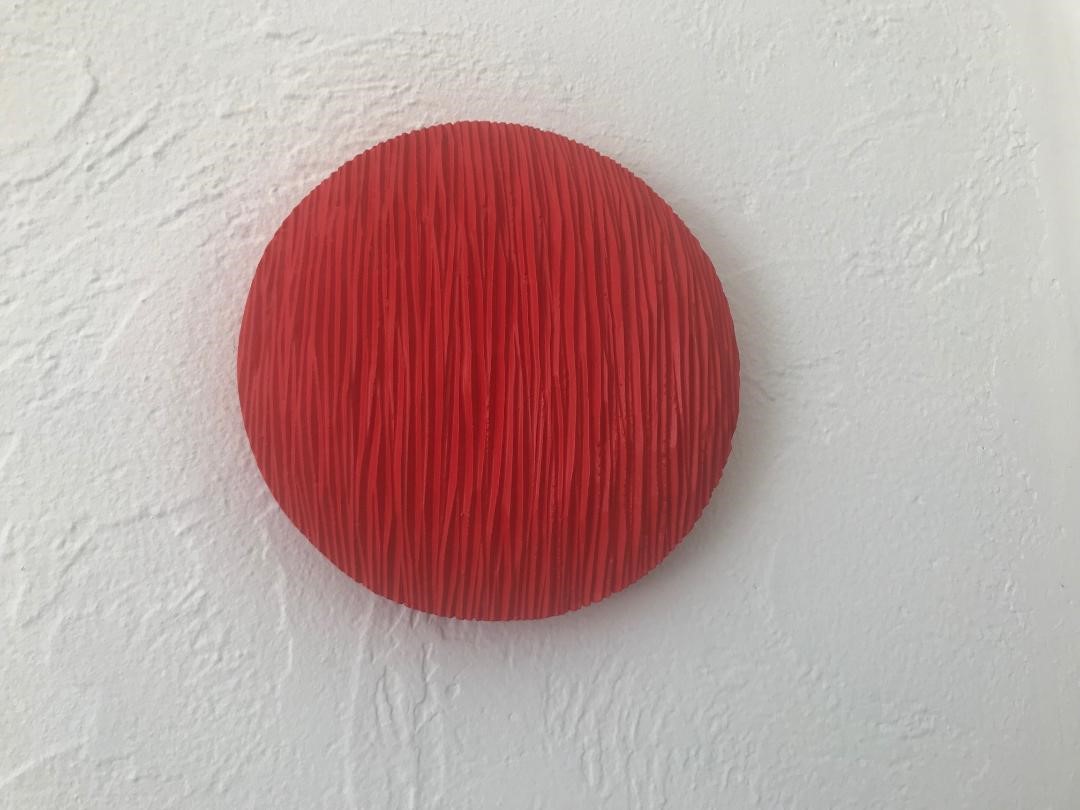

Something very peculiar happens when you approach the multi-tiered wooden sculptures of Japanese artist Masayuki Tsubota. His carved and painted vertical towers appear to change form. The towers are masterfully built up of subtly convex square layers carved from basswood and painted in bold acrylic hues so that their forms are “flexible.” As the viewer moves around the gallery space, the central core of the tower appears to taper and swell depending on the viewer’s position, creating a sort of visual vibration. I recently encountered one such work, a red tower made up of carved wooden squares, at MOË Gallery in Los Angeles (on view until 17 July) while Tsubota was still in Los Angeles. As I walked back and forth and around the piece remarking aloud at its variable form, the artist laughed and nodded, clearly pleased that it was having the desired effect of making me question my sense of reality.

Gesso, pigments, and acrylic on basswood, 20 x 4.5 centimeters.

Image courtesy of the artist and MOË Gallery. Photo by the author

Masayuki Tsubota was born in Osaka in 1976, graduating from Osaka University with a master’s degree in arts in 2004. Since then, he has worked primarily in carved and painted wood. Over the last 15 years, he has become renowned for his simple, elegant sculptural forms that combine a refined sense of modernism with the warmth of handcrafted work. The surfaces of many of his pieces are textured with chisel marks and coated with vibrant traditional Japanese mineral pigments in a poetic union of sculptural technique and painting material. In some works, he partners these textured pieces with works that are coated in gold, silver, and tin leaf, creating a rich harmony of contrasts that can be evocative of gentle land and seascapes. Working in a range of sizes, Tsubota features his work in regular gallery shows in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, and has been commissioned to create works for installations in more than 80 public spaces, including the Intercontinental Hotel in Osaka, Tokyo Gardens Terrace Kioi in Tokyo, and Nanggang Station in Taipei.

Gesso, powdered mineral pigments, glue on basswood, and tin foil, 30 x 50 x 5 centimeters. Image courtesy of the artist and MOË Gallery

Gesso, pigments, and acrylic on basswood, 58.5 x 23 x 20.5 centimeters.

Image courtesy of the artist and MOË Gallery

Tsubota also draws a connection between his work and elements of Buddhist architecture, particularly the pagodas that are important elements of Japan’s oldest temple complexes. Originally evolved from the Indian stupa—burial mounds housing the relics of great teachers or rulers—the East Asian pagoda is typically a wooden structure with multiple tiers, typically five or seven in Japan. Because pagodas also house sacred relics, Buddhist practitioners have traditionally circumambulated these structures in a type of walking meditation. Similarly, Tsubota’s layered towers, with their odd numbers of storeys, invite the viewer to walk around them in an almost spiritual exploration of structure, form, and reality.

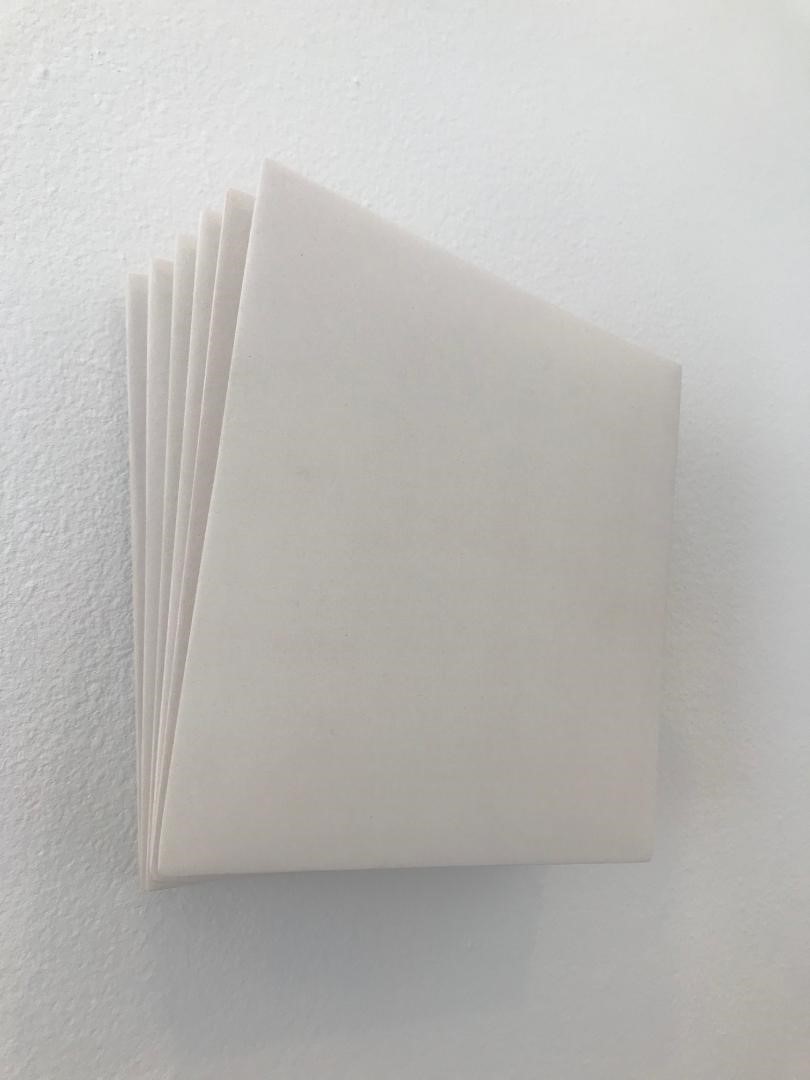

Gesso on basswood, 23.5 x 23 x 8 centimeters.

Image courtesy of the artist and MOË Gallery

Gazing at another of Tsubota’s sculptures, formed of layers of white wood, I again found myself questioning the reality of what I was looking at. The squares of wood, painted to look like sheets of paper, tilted toward me as if peeling away from the white gallery wall. The piece appears at once strong and secure, yet fragile and unstable as it leans out toward the viewer. I could not help but begin to examine the concept of strength and stability in the artwork and in human existence. Tsubota’s exploration of human life in a daily diary of carved and painted wood gives us plenty to contemplate as we look outward to the art, but even more as we look inward to our selves.