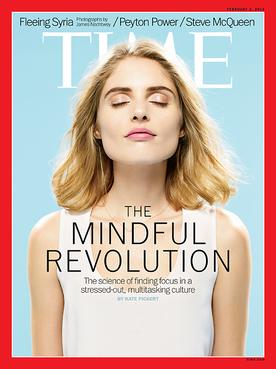

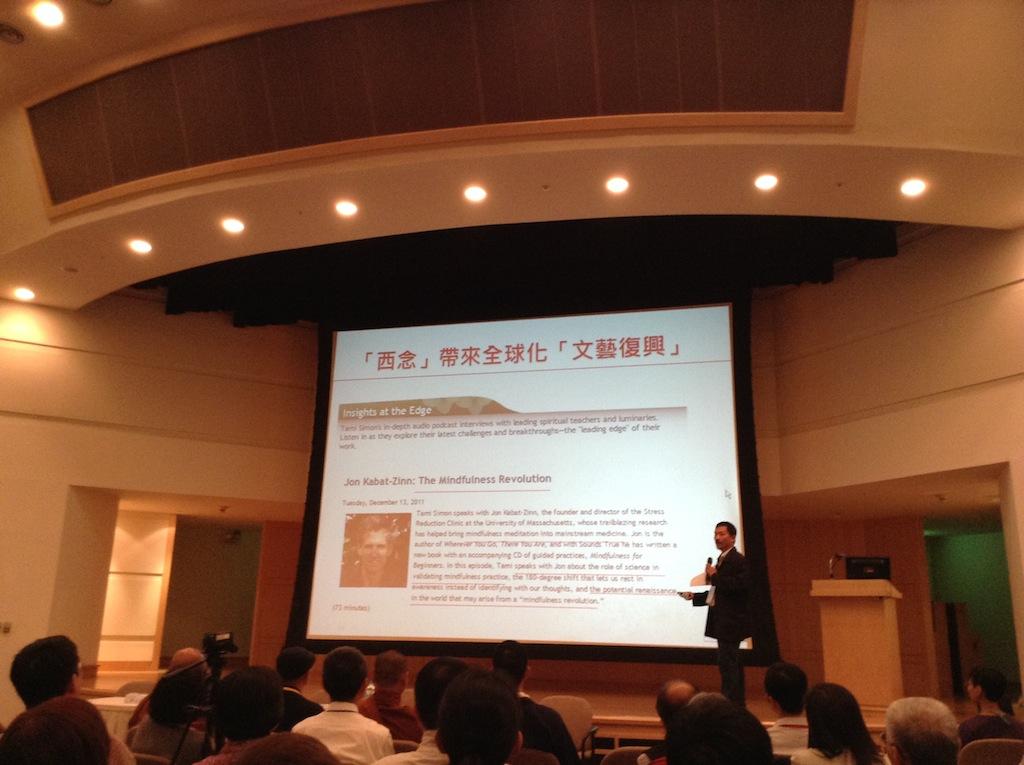

In February this year, Time magazine included a feature called “The Mindful Revolution” as its cover story, illustrated with an image of a girl meditating peacefully. With the great efforts to research and promote mindfulness-based programs in the past three decades, initiated by Jon Kabat-Zinn, the creator of the well-known Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program in 1979 and professor of medicine emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, it seems that mindfulness has been accepted as an icon for enhancing well-being and reducing stress in a scientific way both in the West and in Asia in the 21st century. Nowadays, a two-month mindfulness program is recommended by many medical professionals, not only to patients with chronic or psychosomatic illness or depression, but also to healthy people such as the staff of transnational corporations, including Google and Facebook. Perhaps more surprisingly, mindfulness has been practiced by prisoners and the armed forces in the US and by Members of Parliament in the UK. However, some scholars in the field of Buddhist Studies have voiced doubts and concerns over the interpretation of the term “mindfulness.” And recently, both in the West and Asia, there has been debate and discussion on whether mindfulness should be practiced at all in a secular way without reference to Buddhism. But can mindfulness really be separated from Buddhism? Two conferences that I attended in the past few months may provide some insights into the issue.

Why is Mindfulness so Popular?

This July, the UK Association of Buddhist Studies held its annual conference at the University of Leeds on the theme “Buddhism and Healing.” One of the speakers, Dr. Joanna Cook (University College, London), discussed the recent popularity of mindfulness practice in her talk “Why is Mindfulness so Popular?” Many in Britain are aware that the eight-week Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) program has been recommended by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) as an effective tool in dealing with depression relapse. Cook, a medical anthropologist and the author of Meditation in Modern Buddhism: Renunciation and Change in Thai Monastic Life (Cambridge University Press, 2010), who is working with participants in the MBCT program, commented that over the past decade, mindfulness has been promoted in the UK as being scientific and rational. She explained that mindfulness is normally defined as “paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, without judgment,” which was proposed by Kabat-Zinn in the medical and clinical context. The theory is that the practice of mindfulness can help a person to attain self-transformation by creating possibility of choice. Hence, physical and mental health can be improved through engaging with life in a more skillful way.

The Separation of Mindfulness and Buddhism

On the other hand, Cook recalled that MBCT is in fact a marriage between intensive mindfulness meditation and the conceptual framework of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In the early 1990s, psychologist John Teasdale attended a talk by Ajahn Sumedho, the great disciple of the famous Thai meditation teacher Ajahn Chah, on the four foundations of mindfulness (body, feelings, mind, and Dhamma) at the Oxford Buddhist Centre. Realizing that the four foundations related to daily life, he and two other psychologists (Mark Williams and Zindel Segal) developed the MBCT program after ten years of serious experimentation and research in the UK, with Kabat-Zinn’s support. Although traditional Zen practices are among the exercises in the MBSR program, Buddhist Dharma is not mentioned as such. And in the MBCT teacher-training program, while Buddhist psychology is included in the curriculum, not a single Buddhist term appears in the index of the MBCT teaching “bible”—Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse (Guilford, 2002). Cook observed that therapists refer neither to Buddhism nor to any other religion in the MBCT group teaching, and if the patients start to talk about the Buddha in the class, the therapists bring them back to the practice. Yet, poems from various ancient religious traditions, including Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity, are shared for their insights. It is indeed impossible to imagine that a General Practitioner (a medical doctor in the UK) from the National Health Service (NHS) would promote Buddhism to his/her patients. Mindfulness is presented as divorced from Buddhism, especially in the medical context—recent evidence-based research on brain waves, well-being, and physiology has shown that it can be a pragmatic skill for changing both the mental and physical state.

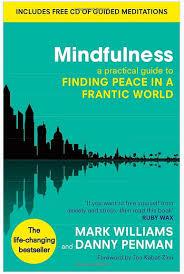

The rapid growth of mindfulness in many sectors and levels of society also relates to social needs and policy changes. Cook mentioned that the WHO has speculated that depression will develop as the third greatest health problem and economic burden, after heart disease and cancer. In 2010, prime minister David Cameron set up a “Happiness Project” to explore “Happiness Economics,” a study of happiness and social factors, and to try to improve national well-being in the UK. One of its goals is that each individual should be responsible for his/her own happiness, with mindfulness put forward as one of the methods. So far, 85 MPs have completed the mindfulness course after Chris Cullen, an MBCT teacher from the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, started teaching it in Parliament beginning in early 2013. Some teachers are promoting mindfulness in schools, some banks are encouraging their customers to spend money mindfully, and mindful eating and mindful management and so on are also being recommended. No wonder Finding Peace in a Frantic World (Piatkus, 2011), written by Dr. Danny Penman, a journalist, and Professor Mark Williams, the previous director of the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, has been the Number One best-seller on Amazon for many months. Scientists, politicians, psychologists, and educators are all practicing mindfulness in order to find peace in this frantic world.

Some, however, have expressed concerns about seeing mindfulness as a panacea. Kabat-Zinn mentioned in the MBSR teacher-training retreat in Beijing that some teachers had also misunderstood the technique of the practices, and were guiding them incorrectly. In a Special Issue of the academic journal Contemporary Buddhism (2011), various Buddhist scholars, such as Bhikkhu Bodhi and Professor Rupert Gethin, discussed the definition of mindfulness, with Bhikkhu Bodhi questioning the popular understanding of mindfulness as “bare attention.” By exploring the Pali text, he also discussed the role of “clear comprehension” (P. sampajanna) as an essential link between observational awareness and insight, something that is missing in the mindfulness programs in the West. Rupert Gethin reviewed the history of accepting “mindfulness” as the English translation of the Pali term “sati,” and proposed that careful reflection is necessary in highlighting mindfulness as “non-judgmental” in mindfulness-based programs.

In the past decade, mindfulness-based programs such as MBSR and MBCT have also been introduced in Chinese societies like Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as in mainland China. These programs are welcomed by professionals, especially in health care, social welfare, and education, for their role in helping vulnerable clients, and Jon Kabat-Zinn and Mark Williams have visited these places to give professional training—Kabat-Zinn is in fact visiting Taiwan for training this month.

Nevertheless, at the first annual conference organized by the Taiwan Mindfulness Development Association at Taipei Koo Foundation Sun Yat-Sen Cancer Center on 12 October this year, one of the speakers, Dr. Yit Kin-tung, an associate professor of National Sun Yat-sen University working on Indian Buddhism, pointed out that the mindfulness practice of the Western mindfulness-based programs does not take into account some of the ethical bases of Buddhist practice. In the Buddhist context, right mindfulness is part of the Noble Eightfold Path, which leads to nibbana—the final goal— the other seven practices being right thinking, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right concentration, and right understanding. In other words, those Buddhists who seek to perfect themselves according to the Buddha’s teachings should practice all eight, yet participants who join the mindfulness-based programs are not reminded of this. Kin-tung doubted whether the secularization and diminution of Buddhist practice through the abandonment of its ethical foundation can help people to solve their personal issues. More importantly, some modern, non-religious terms are used to replace ancient Buddhist terms; for instance, “love and happiness” are used for “loving-kindness” practice. Kin-tung argued that the rhetoric used in Western mindfulness-based programs in order to promote health and happiness in a scientific way may well misrepresent and misappropriate the rich and complex Buddhist practices of the East.

At the moment it would seem impossible to draw a definitive conclusion from the debate, which in Asia has only just begun. However, I feel sure that such interesting and in-depth discussions on the different practices of East and West and on the convergence of science and religion will continue for many years to come.

For further information, see:

UK Association for Buddhist StudiesTaiwan Mindfulness Development Association