Better than a thousand useless words is one useful word, hearing which one attains peace.

The Buddha, Dhammapada VIII, v.100

What might be that magic, calming word, I wonder. I am longing for more peace in this noisy, Wi-Fi-infused, automatized culture that is mostly doing the opposite of what it is promising to do—instead, it is making life more complicated and busier. I was at the allotment yesterday morning, doing my usual qigong warm-up and getting ready to meditate, first writing down this question about the word that leads to calm in my notebook, when a chainsaw started off on full throttle somewhere close by. The universe was clearly offering me a teaching. I noticed the almost instant thoughts: “Is this going to ruin my meditation? Will I need to abandon this lovely, peaceful place and meditate at home?”

On further examination, even before that, a physical tightening occurred in various parts of the body, a visceral bracing against the aural impact. This mindful observation opened up a degree of mental space and then, mercifully, the chainsaw stopped—just for a few minutes as it turned out. Enough to feel nourished by the blissfulness of silence and let awareness settle in the heart center. I was curious: might this inner spaciousness be able to encompass the apprehensiveness about the noise starting up again? When the machine resumed, I imagined a person who was simply doing their job—cutting down a dead tree, maybe—and felt much less reactive.

Not just one, but a few words were part of that process that led to more peace, as I reminded myself of some basic mindfulness teachings, going back to the Buddha’s early teachings:

Recognize and let go of craving and aversion. Be kind—open the heart. In this way you set up the conditions upon which calm and liberation can arise.

Sometimes, when already settled in positive and expansive mental states in meditation, simply feeding in the words “calm” or “peace” may be enough. But it doesn’t work well, in my experience, when there is an activation of the threat system. Then it’s like one angry or anxious part of the psyche trying to help another angry or anxious part by shouting “relax!” and feeling frustrated at the lack of success, which then adds further aggravation. We can, however, do our best to get in touch with a wise, kind, calm part of ourselves that has some perspective on the mechanisms of physical/mental/emotional tension and its release. It knows the password into deeper stillness—“allow”—and is aware of the gentle tone of voice in which it must be spoken. It may say “listen”—listen to the very sound you were resisting; surrender resistance to it.

About 15 years ago, I went to the Spanish Pyrenees for a month-long solitary retreat, staying in a very basic but beautiful eco-cabin* nestled in the oak- and pine-covered hills at the foot of a dramatic yellow sandstone cliff. There was minimal contact with the outside world and no digital input. In settings like this, a line of a poem by Wendell Berry often comes to mind:

I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief.

Gradually, over the weeks that the solitude and wildness were working on me, my mind recognized that, despite all its clever reasoning, ultimately it wasn’t different from the simple suchness of nature. I saw no one on my walks past abandoned dwellings, crossing over smooth rocky galleys shaped by waterfalls dried up thousands of years ago, hot, dry air purifying my lungs with traces of rosemary and thyme. If I needed to pee, I would squat in the middle of the path, confident of not being overlooked by any human beings, only the vultures circling high above the cliffs. I was absorbed in watching the yellow trickle zig-zag toward the valley, the earth too parched to immediately absorb the moisture. I am not quite sure why this scene is lodged in my memory—this giving back something to the earth that essentially belongs to it, the utter rightness and peacefulness of it.

My time there wasn’t all bliss, of course. During that summer, the valley saw an invasion of processionary caterpillars, millions of them, crawling up any vertical surface—trees, walls, legs—following each other in long rows, head to tail, proceeding relentlessly until most of the pine trees in the region were stripped of their needles. The hairs they release are poisonous and make one’s skin itch. I found them on my body, on my pillow, in my mug of tea. They invaded my waking and sleeping consciousness and continuously challenged my equanimity, like the non-stop sound of a chainsaw.

As humans, we do, again and again, tax our lives with “forethought of grief.” We are wired to apprehend danger, envisage the future for all kinds of reasons, and often it really is a big challenge to stay present and remain calm. Calm should not be mistaken for inactivity—in many situations, taking action is a wise choice. I didn’t simply bear the itch and the feelings of alarm, I regularly brushed those caterpillars off the ceiling of my cabin, I drew them in my sketchbook and wrote about my struggles in my diary.

With larger issues in the world, I carefully consider my contribution—I may take part in campaigns or offer Work that Reconnects workshops with titles such as “Healing Self and Our World.” And yet, when we sit down to meditate, stillness is a very attractive proposition. I wrote some poetry on that retreat, as one does. Here is a poem that was a piece of advice to myself.

All thoughts have been thought

All stories been told

All worries dealt with

Be here now—be here

All pain has been grieved

All justice achieved

All debts have been honored

No more now—no more

And so on, with several more verses in that vein. Back home, when I read this to my poet-husband, he commented that it sounded like death. I think it was born from a desire to relinquish the Self, restlessly and noisily clamoring for confirmation of its existence—a desire for spiritual death, opening the door to deep inner peace, nirvana. Since then, my understanding has possibly matured somewhat and my perception of calm includes the ever-changing movements of the mind.

Under certain conditions, we can have transformative glimpses of deeper levels of calm, but we don’t have to spend months on retreat in wild places. We can do a few things that create favorable conditions to enhance a sense of vibrant stillness and to minimize mental agitation, wherever we are. A regular daily meditation practice is a mainstay for this and it becomes more rewarding when we don’t have to process an overload of experience. In fact, knowing how much more satisfying meditation can be when life overall is simple, is a powerful incentive to reduce input of a particular kind. We are probably used to exhortations to limit the use of our smartphones, social media activity, digital entertainment, and not cram our diaries with appointments. But one counter-intuitive piece of advice is to actually stimulate the senses. We don’t like to be told not to do things, but we may be more open to an invitation to hear, smell, taste, and touch more vividly. Inevitably, sensory awareness brings us into the present, giving the churning mind a break. We can’t easily be absorbed in listening to birdsong and worrying about what someone might think about us. Among the many everyday opportunities for this shift into sensory presence, the arts can be a particularly rewarding mine to explore. I particularly like immersive, interactive works of art that aren’t just about seeing.

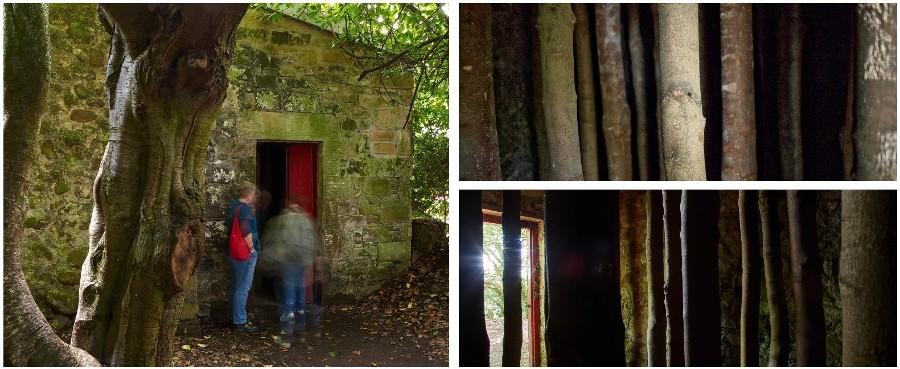

During our recent visit to Jupiter Artland in Scotland, we almost missed Andy Goldworthy’s Coppice Room. The entrance is a small, unremarkable, painted wooden door at the end of a stone wall, a place where you might expect gardening tools to be stored. Upon entering you are immediately enveloped in the scent of pine wood, as you realize you have, bizarrely, stepped into an indoor wood, with smooth tree trunks situated close to each other, floor to ceiling. It is dark, so your sense of touch, smell and hearing intensifies, as it does when you can’t see your way in a midnight forest. You drop into a larger, quieter inner space that is home to a different kind of knowing. You realize that you can squeeze your way through this strange landscape, some trunks too close together, some with gaps just wide enough, your back and belly know where to go. You wind your way deeper into the dark depths of the room, letting your fear of the dark be teased, listening for the crunching footsteps of fellow explorers, until you can’t go any further. You turn around toward the light that beckons through the open door like a celestial visitation. Now the eyes play a larger role as you meander among the boles, occasionally startled by the ghostly, backlit appearance of another human being. Stepping back into the usual world, a sculpture park populated by a crowd of visitors, it feels just a little less predictable, a little less predefined in its reality. An inner, quieter space has been created where things can appear more fluidly as they are, and the wanting mind has been stilled. A space where just being present is enough.

Enough. These few words are enough.

“Where Many Rivers Meet” by David Whyte

If not these words, this breath.

If not this breath, this sitting here.

References

Buddharakkhita, Acharya, trans. 2013. “Sahassavagga: The Thousands” (Dhp VIII). Access to Insight (BCBS Edition). http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/kn/dhp/dhp.08.budd.html.

Whyte, David. 1990. Where Many Rivers Meet. Langely, WA: Many Rivers Press.

Related features from BDG

Being Like a Mountain: What Hokusai’s The Great Wave Says About Remaining Calm in Troubled Times

Magic

Art, Magic, and Hidden Realms

Dharma in Poetry

Touching the Earth: An Ecodharma Retreat