The traditional material utilized by a Buddhist sculptor (Jpn: busshi) in Japan, especially from the Heian period (794–1185) onward, was wood. Apocryphally, this is because the Emperor Shо̄mu (r. 724–49) exhausted the entire Japanese archipelago of its naturally occurring ores to make the Tо̄daiji daibutsu, or giant buddha, depicting Birushana. More realistically, wood was a more plentiful resource, easier to move and sculpt, and was much less expensive for an arguably more dynamic and lifelike result. The artisanry of the master sculptors—started by Torii Busshi in the Asuka period (538–710), epitomized by the Kei school (Jpn: Keiha) during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), and reformed by the Edo period (1603–1868) “master of natabori” Enku (1632–95)—is still practiced to this day, with more than 1,400 years of tradition. And given the growing pains Buddhist sculpture endured and ultimately flourished through—uchiguri, warihagi, yosegi zukuri, and gyokugan—it stands to reason that a discussion regarding the use of 21st technology for making Buddhist sculptures should follow. Enter Takuma Kamine (b. 1978), a lover of Buddhist statuary and an active Japan-based artist using modern resin casting and 3D-printing techniques.

As a child, Kamine was often taken around to the temples in Kyoto, which is where he first encountered butsuzо̄, or statues of Buddhist deities. Despite having no knowledge of who or what these butsuzо̄ depicted, he could tell they were something special, sensing the mysterious ambiance they exuded. And though they were intended to inspire confidence in adherents, Kamine found himself terrified of them. He recalls, “Perhaps my young mind was just trying to get a sense of the universe, but at the time, I didn’t understand what this feeling was, and it burned itself deep into my mind.” But it was not as if the idea of larger-than-life protectors were foreign to the young Kamine; it was around that time that he became fascinated with “mecha,” mechanical space suits and giant robots popular in Japanese comics and animation, which were either themselves sentient or able to be controlled by a human pilot. The similar aurae of the vastly disparate characters, for lack of a better term, so touched him that even in his adulthood he feels the need to explore this emotional response.

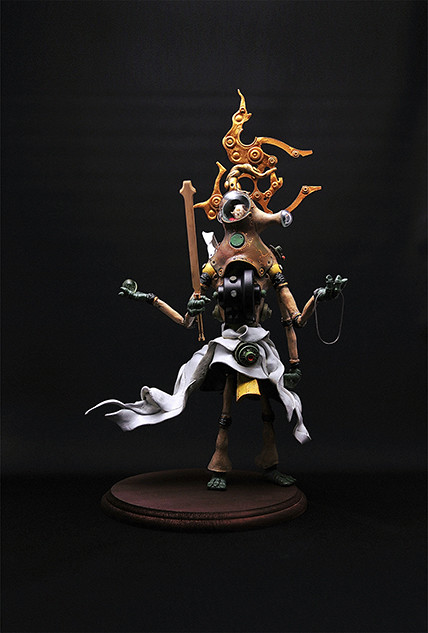

One project by Kamine, called Gardiens, focused on a series of 30–50 centimeter 3D models. The name of the series refers to the kenzoku, or emissaries, of which there are thousands in the esoteric pantheon—most of which are not known except by the most specialized of scholars. Kamine called some of the deities by their popular name—such as Fudо̄ myо̄о̄ (Skt: Acalanatha), Gо̄zanze (Skt: Trailokyavijaya), and Jikokuten (Skt: Dhrtarastra)—and others he gave a name that was slightly more obscure (even if their imagery was associated with a well-known grouping)—Naraenkengо̄, one of the Niо̄ temple gate guardians; and the snake general of the celestial realm, Sanchira taishо̄. Notably missing from the series was a figure representing any of the numerous buddhas whom the kenzoku traditionally guarded. When asked why this was, Kamine responded: “As [the] Buddha is perfect in every way, he lacks dramatic human-ness. I wanted to show the synergy that occurs when the human-like backbone possessed by the Kenzoku is integrated with a variety of modern phenomena.” This response is likely grounded in the idea of the Buddha as an aspiration outside of time and therefore not as affected by modern developments as one who struggles through the realms of existence. Because the kenzoku were adopted from Hinduism and Brahmanism, and are not of Buddhist origin, they are classified as ten-bu, celestial protectors of the Buddhist cosmos. Despite being deities, then, they are still mortal and therefore subject to the karmic accumulation which will decide their next existence after passing on.

Although he has an intimate knowledge of these deities—he does, after all, pore over the sutras, their commentaries, and their accompanying diagrammatic images (Jpn: zuzо̄) for accurate descriptions and depictions—I hesitate to say with any confidence that Kamine would call himself a modern-day busshi. Not because he doesn’t create stunning and awe-inspiring models inspired by Buddhist statuary, but because he sincerely respects the process that created the originals. What Takuma Kamine does is pay homage to his childhood experiences in the Kyoto temples in his own unique way, with his own unique tools.

If you find yourself in Los Angeles during February 2019, you can ask Takuma Kamine himself about his thoughts on 3D printing as a technique for sculpture production. He will be showing a selection of his artworks at the Japan Foundation, Los Angeles (5700 Wilshire Blvd #100, Los Angeles, CA 90036) in his solo exhibition tentatively titled Takuma Kamine: Myо̄о̄ in the Shell. He will be showcasing, among others, his resin models of the wisdom kings (Jpn: myо̄о̄) Fudо̄, Gо̄zanze, Daiitoku (Skt: Yamantaka), Gundari (Skt: Kundali), and Kongо̄ yasha (Skt: Vajrayaksa). The title serves a dual purpose: to remind the audience of his inspiration from Japanese pop culture, specifically the film Ghost in the Shell; and just as there is a spirit which inhabits the titular shell, so the essence of a buddha inhabits the wrathful form of a myо̄о̄ to enforce his intent. If you plan on attending, read up on the concept of sanrinshin!

See more

Great piece and fantastic art.