The following text is taken from a talk given by the author for BDG’s online conference “Buddhist Voices in the Climate Crisis” held on 29–30 July 2022.

Welcome to the Anthropocene—an age in which human activity is the dominant influence on planetary geology, atmosphere, and ecology. As the Buddha famously preached, everything is burning. Burning with the fires of greed, hatred, and delusion. And now the fires are literal. In our species’ craving and delusion, we have set fields and forests on fire across wide swathes of the world.

The image above is an untouched photograph that I took at the Berkeley Marina in California in September 2020, when a hellish glow fell over the Bay Area from fires to the north. The ravages of a global climate emergency are not something that will just slowly emerge in our children or grandchildren’s day. The emergency is here, now, manifesting as unprecedented heatwaves, fires, drought, hurricanes, floods, and rising seas, and the side effects of famine, refugees, and wars, as nations and people contend for resources and survival. As a species, we humans are doing this to ourselves; a kind of mindless self-destruction driven by the three poisons. And, of course, we impose this new reality on so many other species on the planet. In the end, it may be that only cockroaches will be the victors.

In the first half of the 13th century, when our Soto Zen ancestor Eihei Dogen was establishing his practice in Japan, the average level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was roughly 275 parts per million (ppm). When Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, my teacher’s teacher, was practicing in San Francisco in 1970, CO2 levels had reached about 325 ppm. Today’s level is 420 ppm, a measure not seen on Earth for at least 20 million years. Since 1950, fossil-fuel consumption has increased nearly eightfold, doubling since 1980.

What does this mean? Carbon dioxide is the most significant “greenhouse gas,” absorbing heat, trapping it in the atmosphere, and reflecting it back widely, raising temperatures around the globe. Without CO2, the planet would be a ball of ice. Base levels of CO2, for thousands of years, have been naturally generated by the decomposition of organic matter, forest fires, and volcanic eruptions. Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, around 1750, human activity—particularly the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas, and mass deforestation—has increased CO2 levels at an alarming and accelerating rate.

Rising CO2 levels bring rising temperatures. Since the mid-19th century, the average rise in global temperature has been about 1.2ºC. This doesn’t sound like much, but already it has given us the warmest decade in recorded history. And so we have massive fires, droughts, and the displacement of populations in the global south, unusual and extreme weather patterns, melting ice sheets and glacial retreat, rising sea levels endangering shoreline populations, and ocean acidification that threatens sea life.

To return for a moment to our ancestor Dogen, when writing about dana paramita, the perfection of generosity, he wrote poetically:

Giving means to be not greedy. Not to be greedy means not to crave . . . Give flowers blooming on the distant mountains to the Tathagata.*

In Dogen Zenji’s time, the hillsides were green and wildflowers grew freely. To “Give flowers blooming on the distant mountains to the Tathagata,” might simply mean to see and appreciate them by virtue of the buddha-nature that people, flowers, and hillsides all manifest interdependently.

In our time there is an ominous undertone to Dogen’s expression. My first glimmerings of environmental awareness came in the early 1970s through songs about strip-mining in the beautiful hills of Appalachia. Instead of old-fashioned coal mining, whole mountainsides were dynamited and bulldozed to reach seams of coal. In the process, ecosystems were destroyed, watersheds ran black with poison, and local communities were driven off the land. Flowers would never again bloom on these ravaged hillsides. And now global warming has cooked the green hillsides to brown, and there is no welcoming soil in which flowers might bloom. So it takes our effort and dedication to create places where flowers can bloom again that we might offer to the buddhas.

In a world marked by interdependence—another way of expressing dependent co-arising—as we sit and reflect, we understand how numerous aspects of suffering experienced by humans and by all forms of life are interwoven in the fabric of modern life. For example, global warming leads to drought, which threatens food production around the world. The diminution of arable land creates waves of refugees swelling the urban areas of the global south and north. A growing population calls for increased energy supplies, leading to the use of more fossil fuels and power plants. Power plants are often located in poor and marginalized communities, leading to chronic illness and a degraded local environment. We begin to see an endless chain of systemic suffering linked to our use of non-renewable energy.

The question that confronts us as Buddhists faces all peoples: how can we effectively respond to this crisis? Let me say that, while this Buddhistdoor Global conference has an international audience, my reflections and suggestions apply mainly to my own country, the United States, which also happens to be the greatest consumer, polluter, and most prominent driver of the climate crisis.

In a very local and practical sense, our Berkeley sangha and temple wish to align ourselves with change and sustainability. Like many good citizens, we compost or recycle our wastes, and we are dedicated to reducing water usage in homes and gardens. Water conservation is essential since California is in a state of perpetual drought that threatens food production in one of the richest farmlands in the world.

A portion of our center’s energy supply is met by a rooftop solar installation, which we hope to expand in coming years. And we are taking steps to replace natural gas appliances such as stoves and heaters with more efficient electrical appliances. More broadly, Berkeley Zen Center is in the process of creating a long-term plan for environmental sustainability, which includes energy efficiency, water conservation, waste management, and—maybe most importantly—teachings that connect Buddhist wisdom and environmental literacy.

But as much as we need to observe such best practices around energy usage, conservation, and consumer restraint, individual actions are not sufficient to enact the systemic changes needed to save our societies or our planet. Neither can we rely on public demonstrations with well-intentioned slogans and principles. We need to buckle down, come together, and organize a strategic and persistent political presence. In the US, at least, there is still a political space we can occupy.

Like much of the world, my country appears to be moving away from values of liberal democracy toward a more authoritarian future, or shall I say present. The hopes that we might have had five or ten years ago for national legislation and regulation of fossil fuels seem to have evaporated. On a federal level, there is paralysis in our national legislative and executive branches, and a blockage in the highest courts, controlled by a conservative majority that is undoing a century of progressive rulings. (Only recently, the US Supreme Court ruled preemptively to block a provision of the 2010 Clean Air Act which would allow the US Environmental Protection Agency to regulate carbon emissions from power plants.)

This comes at a time when, if anything, countries consuming the most fossil fuels—China, India, Japan, Russia, the US, and in Europe—should be paying reparations to the developing world for the destructive effects of our consumption on their physically and economically vulnerable peoples. Not surprisingly, this growing movement for reparations as an element of environmental justice grows out of calls for reparations compensating African Americans for the ongoing wounds of centuries of enslavement. The deeper we look, the clearer we see that these are not separate issues.

Most recently in the US, along with conservative courts, there is a longstanding stalemate in the legislative branch, particularly in the US Senate, that blocks virtually all progressive legislation. In particular, one senator from a coal-producing state, whose family wealth was built on the coal industry, has demonstrated the power to block the Biden administration’s entire clean-energy program. So a national strategy for the necessary development of significant solar, geothermal, and wind power is off the table. Much of the world looks on us as mad. I can’t blame them.

Since national action is likely to be ineffective at the present, the political field left to us is at the state and local levels. It is beyond the scope of this talk to lay out the many legislative and administrative possibilities, since they vary widely from state to state in the US, and even more widely from nation to nation around the world. But it is essential to understand that building community is the necessary step for action. Organize. Study. Act. Our local communities must link up with state and regional communities, and then we can weave a fabric that connects us globally.

As Buddhists, we know about community. Sangha or community is one of our treasures. We don’t have to build community from scratch. We already have it in our practice. Now, the call is first to review the environmental practices and policies of our sanghas. Some of these may be small steps toward sustainability—installing solar energy, switching out older polluting natural gas appliances, recycling and composting our waste. Such simple practices develop our awareness, encouraging us to participate more widely in actions and even in electoral campaigns that can shift policies in our communities and in our state. On the basis of these first steps, our sanghas can align then themselves with other communities and organizations that share the same values and related practices, and the effectiveness of our actions is multiplied.

Recently, a member of our Zen Center community joined the city of Berkeley’s Environment and Climate Commission, which advises the city council’s plans and policies on matters of sustainability and climate change. Toward that end, Berkeley is establishing bicycle lanes throughout the city, encouraging and building renewable power resources for public and private buildings, and enacting a zero-waste strategy for single-use food-ware and other waste products. The commission is also proposing that the city limits the development of gas stations and other fossil-fuel sales points, replacing them with resources to fuel electrical and hydrogen-based vehicles. In Berkeley’s public schools, the commission is helping to create new curricula for students’ climate literacy.

Underlying the necessity of citizen activism, however, is a deeper issue. We live in the industrial growth world—profit-driven corporate capitalism and state capitalism call for constant expansion of production and markets, and increasing extraction of labor and natural resources from every corner of the globe. Buddhist principles of a “middle way,” of generosity, renunciation, and harmony, are not part of the growth society’s playbook. As long as this economic model is dominant, we are never going address the climate crisis directly. As the accurate but tired metaphor goes, legislation and activism that leaves a growth-and-extraction model in place is like rearranging deck chairs as the Titanic sinks. We need a new economic model based, instead, on dana paramita, the perfection of generosity. In the midst of our more modest and narrowly directed efforts, we should keep this big picture in mind.

Coda

Maybe it is too late. Too late to roll back global warming from our rampant use of fossil fuels. Too late to stop the melting and collapse of massive sheets of ice, the desertification of wide regions of the Earth, too late to roll back the effects of extreme weather across the planet. Even if we are in the midst of what our teacher Joanna Macy calls “The Great Unravelling,” Buddhists have principles and practices on which to fall back.

In meditation we learn to find a home in our self, to locate our self. My old teacher told me I should always know where my feet are. Literally that means: Where am I standing and how am I standing? Can I sense the shoulders of ancestors holding us upright, steadying us to move forward?

In our practice we recognize that we are not alone, either in loss or in our modest successes. We sit upright—together. We act without depending on immediate success or failure. We act because turning toward life is the human thing to do. We have each other to rely on. Keeping this in mind, again here is guidance from Joanna Macy: “I’m doing this work so that when things fall apart, we will not turn on each other.”

At last, relying on the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha to steady our minds, we can act to preserve the most precious human values, regardless of what comes. Because it is so easy to fall into despair, even if only two people remain to walk the planet, we must rely on love and relationship, and value the gifts of the Earth that sustain us.

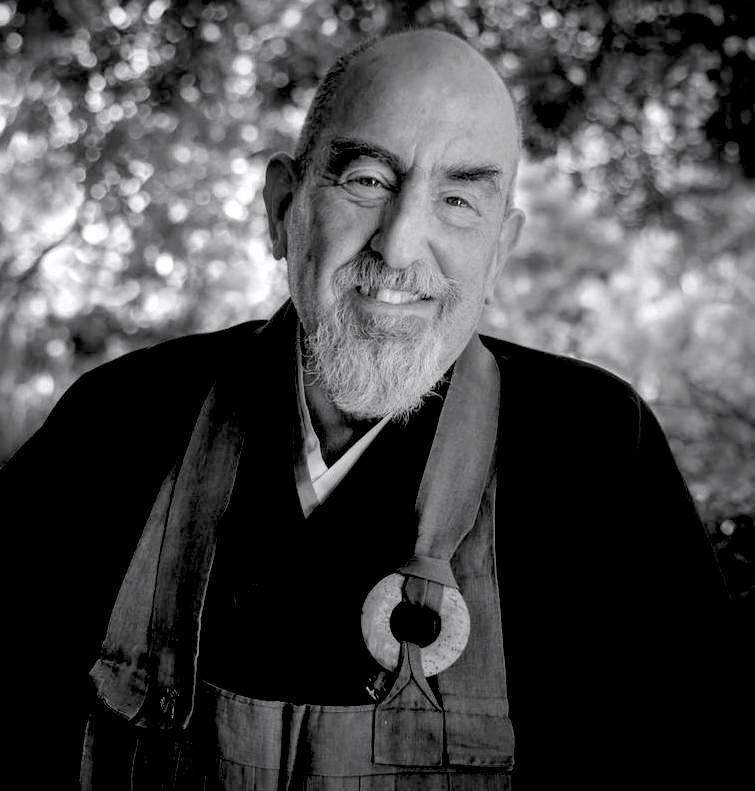

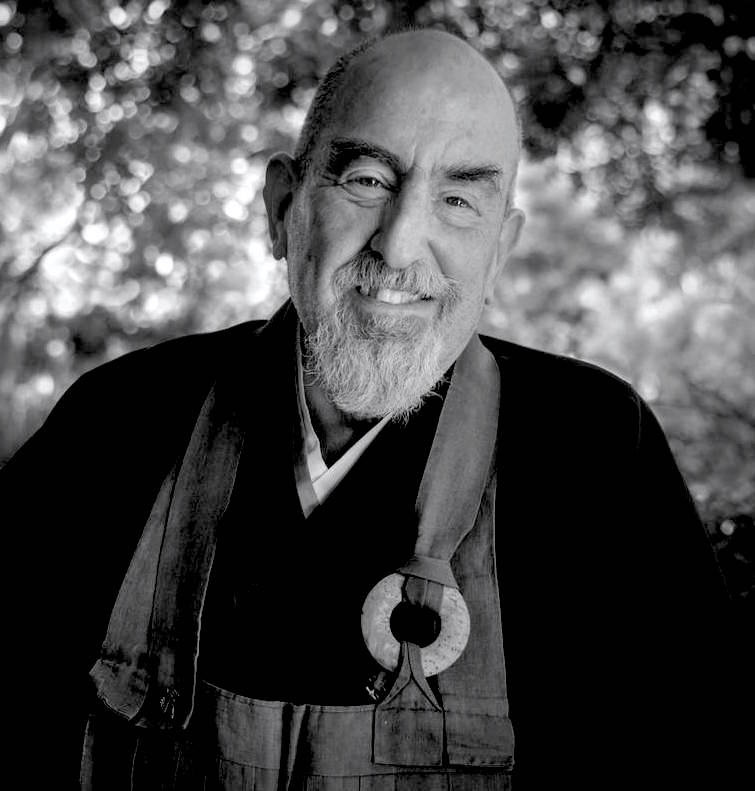

Hozan Alan Senauke

Berkeley, California

September 2022

* Eihei Dogen: Shobogenzo: Bodaisatta-Shishobo—The Bodhisattva’s Four Embracing Actions.

References

Loy, David. 2019. Ecodharma: Basic Teachings for the Ecological Crisis. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications.

See more

Berkeley Zen Center

Clear View Project

International Network of Engaged Buddhists

For further investigation

One Earth Sangha

Rocky Mountain Ecodharma Retreat Center

Three pillars of Ecodharma (Boundless in Motion)

Daily CO2 (CO2.Earth)

The Atmosphere: Getting a Handle on Carbon Dioxide (NASA: Global Climate Change)

Why Are Reparations Essential for Climate Justice? (Global Citizen)

Related features from BDG

Living in End Times

Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche on Biodiversity Conservation and the Illegal Wildlife Trade

Buddhistdoor View: A New Relationship with Nature

Related videos from BDG

Buddhist Voices in the Climate Crisis