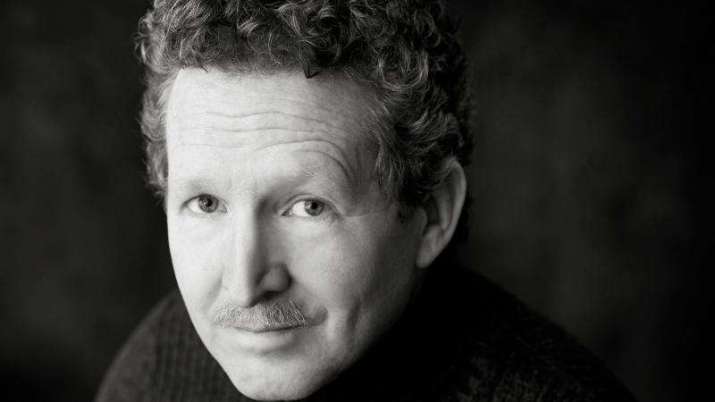

As the Arthur E. Link Distinguished University Professor of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies at the University of Michigan, Dr. Donald S. Lopez Jr. is one of the leading scholars of Buddhism in the United States. Buddhistdoor Global recently sat down with Dr. Lopez to learn about his views on the state of the field of Buddhist studies and his thoughts on the future.

Buddhistdoor Global: How do you understand the current state of Buddhist studies in terms of the longue durée?

Dr. Donald S. Lopez Jr.: I typically trace the beginning of Buddhist studies in the West to Eugene Burnouf and his publication in 1844 of a work called An Introduction to the History of Indian Buddhism. That was really a time when Buddhist texts were making their way to Europe and scholars were learning Sanskrit and Chinese, and it was really the beginning of Buddhist studies as the study of Buddhist texts.

And that remained the model for a very long time, this idea that buddhologists were basically philologists; they are Sanskritists, they are Sinologists. We have the Pali Text Society and the whole implication of colonialism, which is a very long and interesting story. Then we have the coming of the Second World War, and we have various people going to China and Japan in particular, this first interest in Zen coming out of people who were in Tokyo for the war crimes trials. It’s a massive story of the mystique of Buddhism and that makes it way into the academic world, so we have people like Rhys Davis, who began as a colonial officer in Sri Lanka, and more and more texts being translated and making their way into society.

In speaking about North America, it’s really in the post-World War Two period that we see Buddhist studies finding a regular place in academia and that is with the rise of this phenomenon called “the Department of Religion,” which really didn’t exist so much prior to that time. It had been mostly, as you know, divinity schools that were either attached or not attached to various universities. Somehow there came to be the idea that religion should be studied outside of the Judeo-Christian tradition, despite the fact that almost all of the earlier scholars in those departments were ordained Christian clergy or rabbis in many cases. And so there was often the token “none of the above” type person who did maybe “world religions” or “comparative religion,” and we can see the Zen phase, the Tibetan phase, the Vipassana phase, those things making their way into academia in different moments.

Especially in the Vietnam and post-Vietnam period, there was huge interest in these religions on college campuses. So we saw growth in enrollment and hiring in the 1970s, when we had students who wanted to know about these religions—and at that time it was “Asian religions,” as if it was just one category, or “Oriental philosophy,” as if the different Asian traditions were somehow the same. Then, over time, those became differentiated into Phd programs, where you would have multiple buddhologists in different places, who then produced graduate students who would get jobs at different colleges and universities.

So it really has gone from a time of everybody doing a kind of India or China/Japan, to Tibet making its way into the mix, and maybe in the last 20 years, the whole idea that the Buddhist tradition is much more diverse—many more languages beyond the canonical languages, anthropological approaches coming into the academic study of Buddhism, historical approaches, and also just looking at the fact that these traditions extend into the present day.

So this is not simply an antiquarian project, as it had been for so many years, in which one looked at ancient manuscript and tried to figure out what they are about.

BDG: So you have seen very many changes over your career?

DSL: I have.

BDG: What are some of the questions scholars are now asking in terms of where we are in the field? Or perhaps I should say what should they be asking?

DSL: I think there are really a lot of things going on at the same time; I don’t think there is any sort of big theme that is pressing the field. The fact that so many people are doing vernacular languages, being able to talk about Thai and Burmese and Lao Buddhism, Mongolian Buddhism, and to get outside the major India, Tibet, China, Japan sort of model—also Korean Buddhism is becoming very important. I think that has been, in some ways, the most important development because it allows us to take this idea of exactly what Buddhism is and, going from this debate that happened in the field, whether we should even use the term in the singular at all, or if we should just say “buddhisms.”

In some ways, my own view is that as we learn more about the interconnections in more languages and more traditions over a longer period of time, there is a coherence to the tradition that becomes apparent, which may not have been when we had this very strict Indian-Tibetan, Chinese-Japanese divide that doesn’t really remain so much now. When I was in graduate school you did one or the other, but so many students doing Tibetan studies now are doing Tibetan-Chinese because Tibet is part of China, and there are many vernaculars in Tibet, and you can’t speak all the dialects. Everybody speaks Chinese, it’s just a reality and so just a configuration of language study also changes a lot, and it’s been quite interesting to observe.