Tokyo-based printmaker, installation artist, and designer Ayomi Yoshida has spent nearly four decades pushing the boundaries of woodblock printing, an Asian artistic medium that is deeply rooted in Buddhism. Originally invented in Chinese Buddhist temples around 600 CE, woodblock printing was introduced to Japan sometime in the 7th century as a means of disseminating Buddhist texts, with images of Buddhist deities printed soon afterwards. The medium blossomed as an artistic form much later in the Edo period (1600-1868) with the advent of woodblock printed books and single-sheet prints depicting glamorous courtesans, famous kabuki actors, and views of the city and the landscapes beyond. Though mostly secular in content, these printed images became known as ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world.” The term “floating world,” referring to the entertainment provided by urban licensed pleasure quarters and theater districts that provided temporary escape from daily life, originated in the Buddhist concept that life is ephemeral and should be lived in the moment. Yoshida was born into a woodblock printmaking family and has created a fresh, contemporary style that bears little stylistic resemblance to her family’s work, let alone traditional ukiyo-e or Buddhist prints. Yet, many of her abstract prints and her large-scale installations possess a profoundly Buddhist sensibility, one born of a spirituality that has long been present in her life and her work.

Yoshida was born in Tokyo in 1958, the daughter of Hodaka (1926-1995) and Chizuko Yoshida (1924-2017), both noted modern printmakers. Her grandfather was Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950) and her uncle Toshi (1911-1995)—two of the most celebrated “Shin-Hanga” (or “New Woodblock Print”) woodblock print artists of the early to mid-20th century. Her grandmother Fujio (1887-1987) was also an accomplished artist and had a powerful influence on her art and her life, taking her to Buddhist temples and sharing Buddhist ideas and practice with her from a young age. As a student, Yoshida did not intend to pursue the family occupation, choosing to study architecture at college. However, while she was writing her graduation thesis, she conducted some architectural research in California, where she also began exploring silkscreen printing. After graduating college, she wanted to continue making silkscreen prints but was unable to find the materials she needed in Tokyo so turned to woodblock printing techniques instead. Although her family did not directly teach her, she had long been exposed to their work at home and was soon able to carve her own designs out of woodblocks and evolve a new approach to the art form.

Image courtesy of the Tolman Collection, Tokyo, and the artist

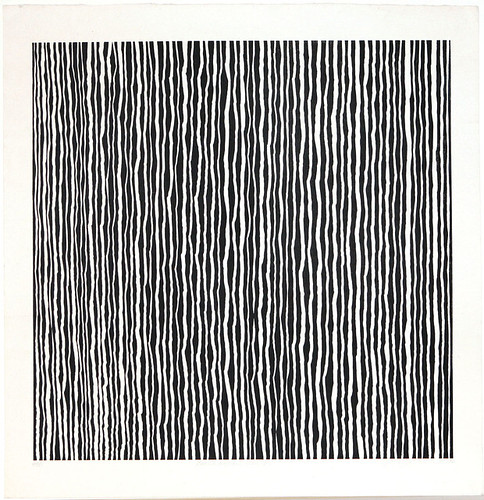

In many of her early prints, Yoshida cut into the wood with her chisel, scooping out oval forms or undulating lines, which she repeated across the surface to create rhythmic abstract patterns, often rendered in black and white or in strong, contrasting colors. Works such as Black Marks, 1998 exemplify the dramatic yet subdued style of these early prints, which are at once modernist in their flavor yet also evoke the calligraphic brushstrokes of Zen masters in paintings and inscriptions that have been created for centuries in Japan as focal points for meditational practice. The lines, though individually ragged and irregular, unite to suggest flowing or falling water and are so perfectly balanced that we question concepts of positive and negative space; are they black on white or white on black? Or both?

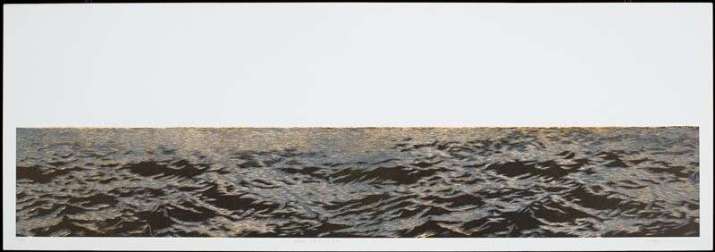

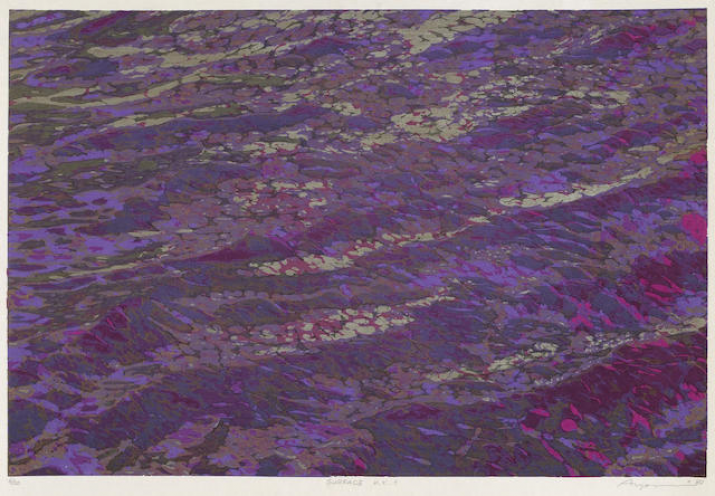

Water remains a common motif in Yoshida’s more recent works. Her Water series, which she originally began in 1987 and then restarted in 2010, are almost photographic representations of bodies of water. In these works, rippling waves on the ocean’s surface are illuminated and made to dance by an unseen light source. In works such as Water 128 I-Y.B.F, a hint of sepia enhances the texture of the surface, adding to the sense of the ocean’s infinite expanse. The contrast of the darkness of the waves and the whiteness of the sky above the horizon invites the viewer contemplate the depth of emptiness.

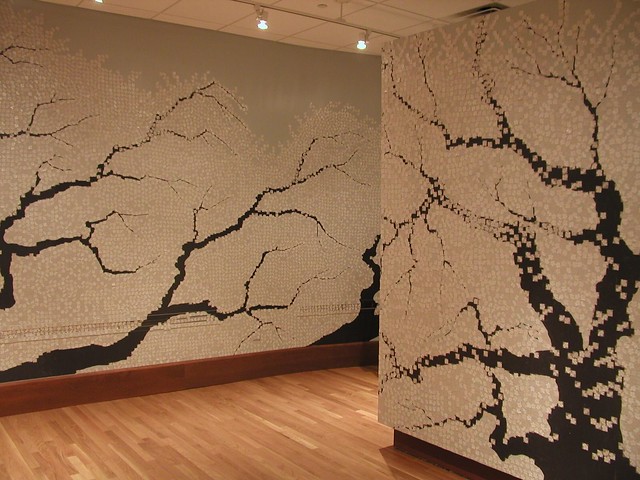

In the late 1990s, Yoshida’s prints grew in scale, evolving into installations occupying large art galleries in Japan and, increasingly, museum galleries in the United States. Over the years, her installations have included woodblock prints, projected imagery, sound, and sometimes even the woodchips that are left over from carving the woodblocks. In 2008, Yoshida created an installation entitled Yedoensis for Northern Illinois University’s Art Museum. For this work and a 2010 reprisal of it, Reverberation—at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design—, Yoshida painted the silhouettes of cherry trees on gallery walls. She then printed tens of thousands of cherry blossom images onto one-inch square sheets of thin paper, and stuck them one by one onto the gallery walls with the help of a team of volunteers, building up a snowstorm of cherry blossoms, like those that fill Japan’s springtime skies. For the Japanese, the cherry blossom is a symbol of ephemerality—the Buddhist idea that everything is temporary, including reality itself.

For a recent installation at the Asia Society galleries in Houston, Texas (on view until 13 January 2019)*, Yoshida suspended hundreds of flower petals from the ceiling, scattered more on the floor of the building’s grand hall, projected a video of rippling water onto the floor, and added the sound of rain falling and thunder rumbling to transform the space into a water garden. Once immersed in this fusion of interior and exterior space, visitors to this city, one that has been profoundly impacted by rains and flooding, can be at peace with water.

For Yoshida, the act of carving into a block of wood to create the design for her prints is a highly meditative one. Though she is not carving imagery that is specifically Buddhist in content, she agrees that there is a deeply Buddhist tone to her work. “Growing up visiting temples and praying with my grandmother had a strong impact on me,” she relates. “I do have a Buddhist approach to much of what I do. When I am carving a woodblock, the act is very contemplative and I can completely focus on what I am doing.” With her installations, she is even more conscious of Buddhist philosophy and ideals. The themes of many of her installations deal with the concept of impermanence, and the installations themselves are also impermanent, arranged in a gallery typically for a few weeks or months. “We have an expression in Japanese ichi-go ichi-e”, she explains. “This translates as ‘one meeting, one time’—meaning that a meeting in a certain place with certain people at a certain time only happens once, so we should enjoy it.” For Yoshida, each installation in a particular gallery is a unique event, and when people come together to view it and enjoy it, “it is a very special moment.” As she brings her woodblock printed artworks and installations to more audiences, she is savoring every single one of these moments.

Yoshida’s work can be seen at www.ayomi-yoshida.com

* See: Ayomi Yoshida (Asia Society Texas)