With the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, in late 2019, and its subsequent development into a global pandemic, Buddhist organizations have sprung into action around the world. Their responses have been diverse, reflecting sectarian and cultural differences, however they have coalesced around certain common themes with deep historical precedents.

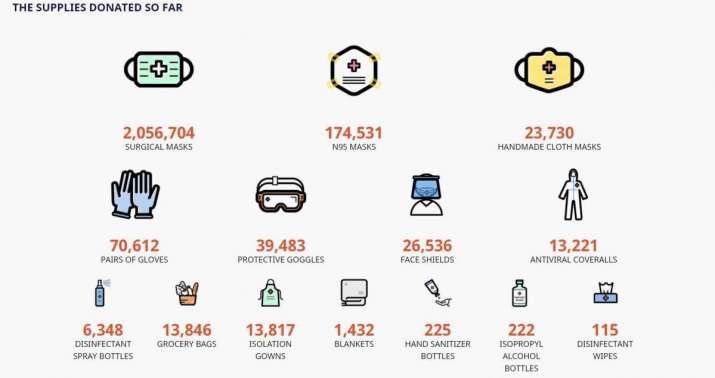

An example of a recent ambitious initiative is the Flatten the Curve project announced by the US chapter of the Tzu Chi Foundation—a massive Buddhist humanitarian organization headquartered in Taiwan that claims over 10 million members and 45 chapters across the globe. In an early April press release, Tzu Chi USA declared that they would deliver millions of masks and other medical supplies to frontline healthcare workers and launch an assistance program for people who have been socio-economically impacted by the pandemic. These US initiatives complement Tzu Chi’s extensive international relief efforts to help to contain and mitigate the effects of the pandemic around the globe. All the while, the organization’s headquarters has been disseminating Dharma teachings specifically tailored for these difficult times. These include “daily reminders” advocating that devotees pray, maintain right mindfulness, purify the mind, cultivate compassion, practice vegetarianism, and treat the disaster as a time for spiritual awakening

Other large-scale responses to COVID-19 include that of Soka Gakkai International, a massive Buddhist organization headquartered in Tokyo with an estimated 12 million members in 192 countries. In a press release dated 10 April, SGI president Minoru Harada announced that chapters in Italy, Malaysia, and the US were donating masks and raising funds to help frontline healthcare workers, while youth members in Japan shared a Stay Home initiative on Twitter.

Also in early April, the Thai organization Dhammakaya took to YouTube to call for its estimated three million members across the globe to come together to “meditate against coronavirus.” The organization called its attempt to accumulate a million minutes of meditation through mass collective action on 22 April an act that would “heal the world.” Meanwhile, the Dalai Lama was using his own considerable media presence to disseminate his response to COVID-19. In a 14 April article for Time magazine, he interpreted the crisis according to the principles of interdependence, suffering, and impermanence, and called for compassion and hope. In a separate article meant for Chinese and Tibetan Buddhists, he specifically called upon devotees to chant the mantras to the deity Tara in order to offer strength and protection against the virus.

We would like to express our condolences to all those affected by #coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

— Soka Gakkai Official (@sgi_info) March 3, 2020

While holding out hope for a speedy resolution to the crisis, let us to do our utmost to prevent the spread of the virus.

#COVID19 #SGI pic.twitter.com/zDaMIQcy7b

The actions summarized here are emblematic of the diversity of Buddhist responses to the coronavirus pandemic. Due to the size and reach of these particular organizations, their initiatives are higher in profile and larger in scale than most others. But Buddhist organizations worldwide—whether Theravada, Mahayana, or Vajrayana, traditional or post-traditional, local or global—are actively involved in supporting their members and communities in similar ways in this time of need.

Generally speaking, many of these Buddhist responses to the coronavirus are firmly grounded in Buddhist doctrine and history. Many of you might be familiar with the Buddhist teachings on the mental and spiritual dimensions of health. However, you may be surprised to learn that it is also the case that Buddhism has for millennia taught specific, direct, and concrete responses to contagious diseases. Measures to combat epidemics are specifically mentioned in major sutras across the major Buddhist traditions. In many premodern Asian cultures, Buddhist monasteries were among the most politically powerful and socially relevant institutions, and thus were frequently influential in mobilizing public health responses.

Outside of formal institutional structures, Buddhist devotees frequently organized mutual aid groups and charitable projects in times of epidemic, famine, and other natural disasters. Many of these historical precedents are echoed in the responses to the current pandemic. Here, I will focus on three in particular: meditation, charity, and ritual protection. The examples mentioned below have been documented by scholars who research the history of Buddhism and medicine, and are drawn from my Buddhism & Medicine anthologies recently published by Columbia University Press.

The power of meditation to promote health is emerging as a central focus of the response from Tzu Chi, Dhammakaya, and other denominational groups. Many temples and meditation centers across the world have made resources such as virtual sanghas and special guided meditations for resilience and well-being available online. Such measures are consonant with the longstanding association between meditation and health in the Buddhist tradition, long predating the 21st century emphasis on mindfulness-based interventions.

Meditation has not only been thought to relieve stress and increase resilience, but also to directly heal physical ailments. For example, meditating on the factors of enlightenment is described as an illness-dispelling practice in a number of early Buddhist texts, for example the Girimananda Sutta from the Pali canon, compiled in the first century BCE. Entire Mahayana treatises have been written on the subject of how a sage who has realized emptiness exerts total control over illness, for example the Vimalakirti Sutra, written c.100 CE). Healing visualization meditations have played a prominent role within Vajrayana practice at least since the fifth century CE, when practitioners began to visualize mantras, divine symbols, or deities entering into the body in order to heal or regulate subtle energies. While the mechanisms whereby these meditations are thought to heal differ from tradition to tradition and culture to culture, the basic notion that meditation can cure or prevent illness is a common thread in nearly all forms of Buddhism.

A second important theme in the Buddhist response to COVID-19 is the emphasis on compassion and generosity for the sick. Charitable initiatives from organizations such as Tzu Chi and SGI are modern iterations of a Buddhist commitment to medical charity that goes back many centuries. Beginning as early as the sixth century CE and continuing throughout the premodern period, historical records show that hospitals and medical dispensaries across Cambodia, China, Japan, Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Tibet were frequently founded and supported by Buddhist donors. These medical facilities were often staffed by Buddhist monastics and were sometimes even located within temple complexes.

Buddhist institutions have sometimes even played a direct role in implementing government public health or disaster relief initiatives at the local level. While premodern hospitals cared for patients with traditional medicines of various types, many Buddhist more contemporary organizations have shifted their support to scientific and biomedical interventions instead. Consequently,Buddhist charitable organizations today actively support or directly administer all kinds of hospitals, clinics, and public health initiatives across the world.

Whether it is Tzu Chi’s daily reminders to pray, SGI’s emphasis on mantra chanting, or the Dalai Lama’s advice to call upon the bodhisattva Tara, another major theme that emerges in the response to COVID-19 is ritual protection. This has been a common concern for Buddhists as far back as written historical records of the tradition go, and continues to be of paramount importance to most Buddhists around the world today.

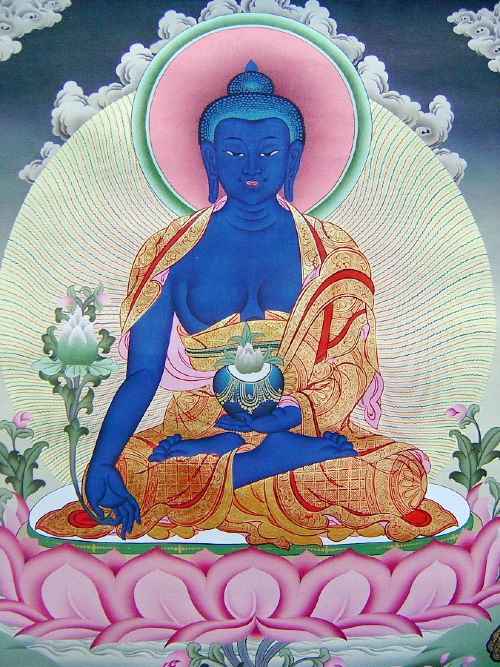

In the early Buddhist and Theravada traditions, specific texts have long been chanted as parittas, safeguards against danger or disaster. In particular, suttas that tell stories of the sudden healing of illness—such as the aforementioned Girimananda Sutta—have been thought to have the power to overcome disease and maintain health due to the magical powers of the source text. Mahayana and Vajrayana practices, on the other hand, tend to focus on invoking or calling forth the blessings of specific buddhas or bodhisattvas. The most popular sutras and mantras associated with healing deities include the Medicine Buddha Sutra, the Great Compassion mantra associated with Avalokitesvara, and the Tara mantra recommended above by the Dalai Lama. We have ample historical evidence that these incantations have been utilized since the medieval period to combat epidemic diseases in both private devotions as well as in massive public ceremonies run by large temples, rulers, or mutual aid societies.

Given their centrality in Buddhist doctrine and history, it is not surprising to see healing meditations, medical charity, and rituals of protection playing a major role in the Buddhist response to COVID-19. Buddhists have almost always taken these measures seriously as medical and public health interventions. How or why they have thought these measures work is a more complex question. The greater Buddhist tradition has carried within it a multiplicity of interpretations of illness that have differed greatly on the basis of school, culture, and geography. In some contexts, Buddhists have predominantly thought of diseases in demonic terms and have sought magical protection. In others, they have been thought of in karmic terms and divine intervention has been sought. In some places, the paradigm of subtle energies has been predominant. Contemporary Buddhists who primarily interpret the tradition through a modern lens may prefer more secular and psychological interpretations of the responses mentioned above. Culturally diverse, geographically expansive, and always multivocal, the Buddhist tradition as a whole continues to speak on all of these levels simultaneously.

Medicine Buddha. From wordpress.com

Buddhist responses to the coronavirus and the interpretations of these practices thus do not necessarily coincide in their specifics. Nevertheless, these responses can be seen to be coalescing around certain themes that have deep histories. What makes them all part of a Buddhist tradition of responses to disease is not the fact that they agree with one another on all counts, but that they are all part of an ongoing millennia-long crosscultural conversation about Buddhism and health.

C. Pierce Salguero is a transdisciplinary medical humanities scholar. He has a PhD in the History of Medicine from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (2010), and teaches Asian history, medicine, and religion at Penn State University’s Abington College, near Philadelphia. Among many publications related to Buddhism and health, he is the author of the multivolume collection Buddhism and Medicine from Columbia University Press. See more information at www.piercesalguero.com.