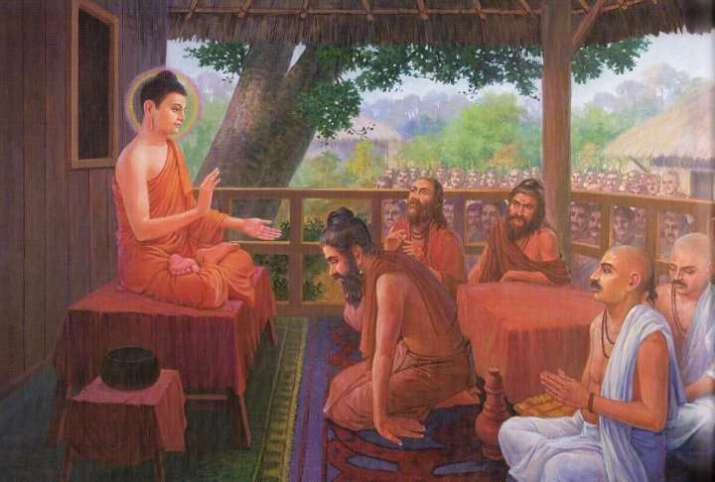

Income and assets play a significant role in the lives and well-being of people. A number of the Buddha’s teachings that relate to material wealth—its acquisition and investment—are more relevant today than ever. In a world where right livelihood is becoming an increasingly urgent moral calling, there needs to be a bold and comprehensive re-envisioning of the acquisition of wealth and how it is distributed and used to uplift communities and individuals. The Buddha’s advice on the use of wealth for the benefit of oneself and others is laid out in several texts in the Pali Canon: the Sigalovada Sutta, the Anana Sutta, and the Vyagghapajja Sutta.

The Sigalovada Sutta of the Digha Nikaya (III 180), a code of discipline for lay life, contains two important verses that sum up the spiritual ideal of what one might call an economically comfortable householder. One passage declares: “The wise and virtuous shine like a blazing fire. He who acquires his wealth in harmless ways like to a bee that honey gathers, riches mount up for him like ant hill’s rapid growth.” It goes on to advise: “With wealth acquired this way, a layman fit for household life, in portions four divides his wealth: thus will he friendship win. One portion for his wants he uses, two portions on his business spends, the fourth for times of need he keeps.” (accesstoinsight.org)

According to the Sigalovada Sutta, if a layperson spends their income and resources as advised, their daily life will not only be smooth and well-run, but make them beloved among their community. Investing in one’s businesses or work lives lays the foundation for further wealth. Due to the accumulation of income in preparation for accidents or misfortune, rainy days will not pour so hard. In both respects, the idea of using what we have to build for more in the future is an age-old ideal that economists and parents alike still teach today: spend prudently, save where possible, and invest what is left over into future wealth creation.

The Sigalovada Sutta outlines injunctions against what its authors saw as not only unconducive to the Buddhist life, but harmful to one’s economic prospects. The Buddha said that householder life will be full of happiness and peace if acquired wealth is not lost from six activities: “indulgence in intoxicants, which cause infatuation and heedlessness,” “sauntering in streets at unseemly hours” (too much clubbing?), “frequenting theatrical shows,” “indulgence in gambling, which causes heedlessness,” “association with evil companions,” and “the habit of idlness.” (Access to Insight)

In the same sutta, the Buddha also advised laypeople to avoid five kinds of trade and commerce. They are the arms trade, animal trafficking, the meat and poultry industry, the alcohol trade, and trading in narcotics. These industries cause indisputable harm in one way or another, and provisions can only be made for those who have no other economic alternative, which is a minority among the total number of people practicing these trades today.

In the Anana Sutta of the Anguttara Nikaya (II 69), the Buddha is said to have delineated four kinds of happiness that a householder can achieve through leading a life endowed with virtue. They are the bliss of having (atthi-sukha), the bliss of using material wealth (bhoga-sukha), the happiness of debtlessness (anana-sukha), and the happiness of blamelessness (anavajja-sukha). The bliss of having and using material assets are interrelated, with the Buddha exhorting that wealth should be earned through effort and enterprise, piled up through the sweat of the brow. As such, “righteous wealth righteously gained” allows the householder to gain merit while also partaking of prosperity. (Access to Insight)

The Buddha’s advice on economic stability (more accurately, worldly progress) can be found in the Vyagghapajja Sutta of the Anguttara Nikaya (IV 281). Here, the Buddha says that there are four factors in the stability of economic life. Once again we see the theme of “legitimately-gained wealth” in the first factor, the accomplishment of persistent effort (utthana-sampada). Regardless of industry, or which sector, the process of the work needs to be skilful and not lazy: “He [the layperson] is endowed with the power of discernment as to the proper ways and means; he is able to carry out and allocate (duties). This is called the accomplishment of persistent effort.” (Access to Insight)

The second factor, the accomplishment of watchfulness (arakkha-sampada), denotes the wise and cautious stewardship of honestly acquired resources. Is money being delegated to the right causes? This applies not only to private funds, but also to government spending and corporate investment. The third, good friendship (kalyana-mittata) is as follows: “in whatsoever village or market town a householder dwells, he associates, converses, engages in discussions with householders or householders’ sons, whether young and highly cultured or old and highly cultured, full of faith (saddha), full of virtue (sila), full of charity (caga), full of wisdom (pañña). He acts in accordance with the faith of the faithful, with the virtue of the virtuous, with the charity of the charitable, with the wisdom of the wise.” (Access to Insight)

The fourth and final factor is balanced livelihood (sama-jivikata), which denotes a disciplined life: not too miserable, not worthless, spending money according to needs, and earning more than one spends. The opposites of these factors, which will lead to the ruin of public and private wealth, are debauchery, drunkenness, gambling, and friendship, companionship and intimacy with evil-doers. (Access to Insight)

It is worth noting that at the heart of the Buddha’s advice is the development of the mind, which is the basis of developing moral character. If the moral character of the masses does not improve, they will not be able to shift the paradigm of economic greed, and discontent and inequality will only grow. Humanity will consume itself in self-centered competition without any regard for long-term cooperation. Economic growth must be complemented by a paradigm of prosperity as inner happiness and community. Only then might it be possible to create the peace in the world we so desperately need.

See more

Sigalovada Sutta: The Discourse to Sigala—The Layperson’s Code of Discipline (Access to Insight)

Anana Sutta: Debtless (Access to Insight)

Dighajanu (Vyagghapajja) Sutta: Conditions of Welfare (Access to Insight)