In a second lecture offered in July at the University of Hong Kong’s Centre for Buddhist Studies, Professor Osmund Bopearchchi continued his discussion of the land routes of the Silk Road, citing several cases of cultural interactions that have been shown through the discoveries of Gandharan motifs in Buddhist iconography.

Enthusiastic traveling monks, who may have accompanied traders and caravan merchants, introduced Buddhism to China at a very early date. They transmitted not only Buddhist philosophy, but also Buddhist iconography to Buddhist centers in Bamiyan in Afghanistan, the Kizil Caves in Xinjiang, and in Dunhuang in northwestern Gansu Province in western China. The events related to the life of Shakyamuni Buddha or stories of his previous births (Jatakas) were of Indian origin, but their iconographic rendering in a Chinese context have additions and omissions corresponding to the tastes of the donors who commissioned them and of the artists who visualized them. Pious traders who sponsored these sumptuous murals to acquire merit may have preferred stories in which the ultimate sacrifice of the Buddha and buddha-to-be are well idealized.

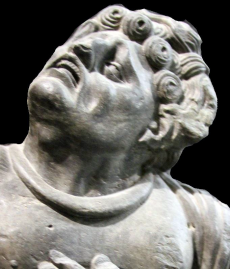

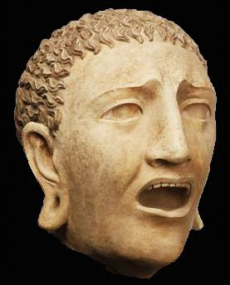

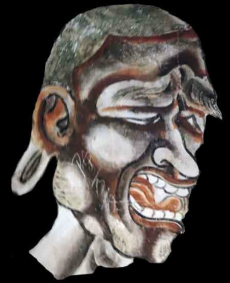

As Prof. Bopearachchi shared, “Buddhism provided new grounds for innovative artistic expression.” He compared images of a sculpture from greater Gandhara depicting the cry of agony of a monk with the agonising layman under the Buddha’s bed lamenting the death of the Blessed One as depicted on a relief currently exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London. The resemblance was not only in the look and feel of the images, but also in the detail of the expressions: in the teeth, tongue, jaw, eyebrows, and staring eyes, all conveying a deep sorrow and cry of despair. Prof. Bopearachchi further pointed out that inspiration could have come from the Hellenistic statue Laocoön and His Sons, also known as the Laocoon Group, “the prototypical icon of human agony” in Western art. This type of iconography directly or indirectly traveled to Dunhuang. The most famous depictions come from cave No.158 in Mogao, known as the Nirvana Cave, which features mourners witnessing the passing of the Buddha, depicted in murals along the length of the hall behind.

The utter despair of the Trojan priest facing his own death (Fig. 1) is the precursor to the passionate and emotional expressions of the agonizing Buddhist monk of the stucco sculpture from the Vardak region (Fig. 2), the pain-stricken layman on the sculpture from the V&A (Fig. 3), and the arahat from theMogao cave No.158 grieving the death of their beloved teacher (Fig. 4). Gandharan art is largely inspired by Hellenistic art, which explains why Greek and Roman mythological stories and images are found in Gandharan Buddhist art and as far as Dunhuang in China.

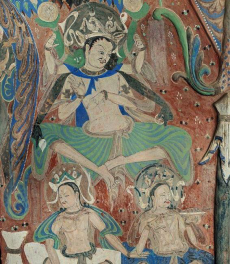

Another example of artistic expression spreading east can be found in the scarf-holding wind god, which influenced art in China and even Japan. The Wind Goddess of Kizil in cave No.38 of the Mogao Grottoes and the headgear of Shiva seated on his vehicle Nandi in cave No.285 are good examples of Iranian, Greco-Roman, and Gandharan inspirations in central China. Although the wind deities are known in Greco-Roman art, the closest parallels to the ones at Bamyan, Kizil, and Mogao come from the Kushan context. The wind god, known as Oado and found on Kushan coins, may have inspired the iconography of the Bamyan and Chinese murals.

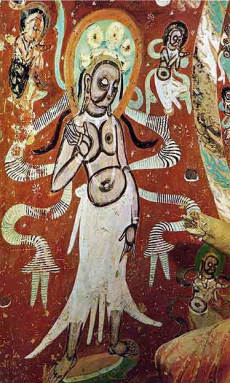

The earliest known depiction of Avalokiteshvara-ekadasamukha is found in No.41 of the Kanheri caves, on the western outskirts of Mumbai. There are 109 caves carved from the basalt and dated from the first century BCE to the 10th century CE. As epigraphical evidence shows, these establishments were built by traders who were associated with the trade centers of Sopara, Kalyan, Nasik, Paithan, and Ujjain. This iconography traveled along the Silk Road. The Mogao and Yulin caves have many depictions of Avalokiteshvara deriving from the Indian prototype, but over time they began to be characterized by additional heads and arms. Mogao Cave No.35, dated to the period of the Five Dynasties, depicts an 11-headed bodhisattva of compassion holding in his eight arms the Sun, the Moon, a trident, and a treasure stick.

The mural on the north wall of Mogao cave No.76 has a symbolic image of the thousand-handed-and-thousand-eyed Avalokiteshvara. The main face has three eyes. Each palm of the eight hands also has a merciful eye. One of the most elaborate versions of the Avalokiteshvara-ekadasamukha is the mural of this bodhisattva of compassion with a thousand hands on the north wall of cave No.3 of the Mogao Grottoes, dated to the Yuan dynasty. The heads are arranged in three rows, one above another, respectively consisting of three, seven, and one head, from the top down. The reputation of Avalokiteshvara as the protector of traders taking the perilous land routes can be seen in the Buddhist cave sculptures depicting the Astamahabhaya Avalokiteshvara protecting humans from the eight great perils.

The stories behind these depictions are Indian, but the artistic rendering of these narrations is Chinese. The Indian iconographies are not simply copied and pasted, but restructured in a Chinese context. Once restructured, the visualisation of the Indian story changes—making Silk Road art a unique mode of expression.

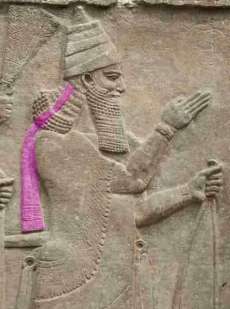

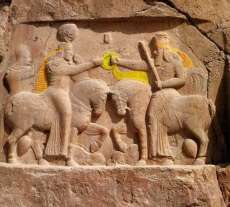

Discussion of the diffusion and reinterpretation of Graeco-Iranian and Gandharan iconography can be further developed by another important motif: the beribboned diadem, also known as fluttering ribbons and flying streamers. These are found behind the heads of buddhas, bodhisattvas, gods, nobles, and traders on the paintings of Bamiyan in Afghanistan, in the Kizil Caves in Xinjiang, and in Dunhuang. Traditionally, the diadem was tied in the back with a reef (square) knot, with the long ends left hanging down. Exactly which ancient culture introduced the diadem remains unclear, but by the late ninth century BCE, the Neo-Assyrian kings were wearing a ribbon around the base of their turbans (Fig. 5). Alexander the Great is also seen wearing a diadem after defeating his opponent Darius III (330 BCE) (Fig. 6). This was in accordance with Eastern practice, which allowed important people to tie their hair with a diadem (Fig. 7); in the West, it was used to imply divinity (Fig. 8).

From the fifth century CE onwards, these motifs were diffused widely in Buddhist imagery (Fig. 9). This occurred to the extent that the divine royal symbolism of the Greeks and Persians lost its specific signification, and nobles, traders, celestial beings, and even animals can be found wearing fluttering ribbons in Buddhist paintings in India, Central Asia, and China. Although these motifs originated in Central Asian and Gandharan regions, they traveled in space and time along the Silk Roads to Buddhist centers in distant lands. As they did, they developed in cross-fertilized cultural contexts, becoming incorporated into the sentiments and aesthetics of their respective populations creating new forms of art (Fig. 10–11).

Having gone through the journey of the discovery of these Buddhist images and hence historical facts, Prof. Bopearchchi takes pride in the passion and effort that goes into sharing this history with people who already have an habitually established perception for a history told otherwise. The resilient spirit in fact-finding will not end. When asked about the one thing he would say to the students who are following his path, in a faithful and sincere voice, Prof. Bopearchchi replied: “Go beyond me!”

See more

Professor Osmund Bopearachchi

Centre of Buddhist Studies, the University of Hong Kong