I recently visited and stayed with one of my relatives in Comilla District of Bangladesh’s Chittagong Division. There I was fortunate to have an opportunity to travel to Mainamati in Comilla, a range of hillsides that is home to a series of Buddhist monuments from South Asia’s medieval period. There are two Shalban Vihars (vihara) in Mainamati: one ancient and one new. As a Bangladeshi national and a Buddhist, I have always been somewhat aware of them, but it was not until I visited them personally that I realized the extent of their significance.

New Shalban Vihar

Established in 1995, New Shalban Vihar sits on a hectare of land that is considered to be the historical site of the much more ancient Shalban Vihar (which I will now refer to as Ancient Shalban Vihar). New Shalban Vihar is a complex consisting of a Buddhist monastery, a meditation center, a novice training center, a school and orphanage, a library, a museum, a seminar hall, a hostel, and a guesthouse.

The latest installation at New Shalban Vihar is the World Peace Pagoda Analayo, which was inaugurated in 2017. It was established by Venerable Shilabhara Mahathera, the abbot of the New Shalban Vihar and an influential Buddhist monk in Bangladesh, with the help of the Young Men’s Buddhist Association of Thailand, and the support of Ven. Phrathepmongkolyarn Analayo, a Thai monk and the abbot of Wat Phutthabucha in Bangkok.

At the entrance to New Shalban Vihar are a number of huge golden Buddhist statues. Among them, the nine-meter standing Buddha statue on the roof can be seen from a great distance. When Sun’s rays move over the sculpture, it shines brilliantly. There are two majestic lion statues of the same colour in front of the main entrance to the pagoda, as well as four big and eight small deities standing to attention. The whole temple is full of different artistic works, all of which have been crafted using metal from Thailand.

New Shalban Vihar is one of the largest Buddhist complexes in Bangladesh. Each day, thousands of Buddhists come to visit from all over the country. On the day we went, the temple was packed with tourists. Arriving a few minutes before the afternoon chanting, we saw crowds of devotees following the monks into the shrine hall, where a giant Buddha statue sat. Ven. Shilabhadra led the Pali chanting, and at the end I had the opportunity to talk with him about this new Buddhist establishment.

During our discussion, Ven. Shilabhadra noted: “After the establishment of the World Peace Pagoda Analayo in Comilla, the aesthetic beauty of this Vihar has increased many times, attracting more tourists domestically and internationally. The vihar has now become even more famous than the ancient Shalban Vihar, which is situated nearby.”

Ven. Shilabhadra also told me that the nine-meter statue on the roof of the prayer hall was imported from Thailand via Chittagong’s seaport in 2009. When he told the Chittagong Port Authority (CPA) that the statue would be used for religious purposes, the CPA waived the applicable tariffs, including storage and port charges.

Ven. Shilabhadra explained that there are about 4,000 Buddhists in Comilla District. “Like the Muslim and Hindu communities in Comilla, Buddhists are living in a peaceful and cordially fraternal environment.” Encouraged by this positive remark, I asked about the tourists in temple. He replied that most of the tourists are Muslims who do not experience any difficulties visiting the temple area. I was also very pleased to learn that there are more than 100 children staying and studying in the vihar’s orphanage. The teaching of the Buddha is one of compassion and loving-kindness toward all living beings. With this aspiration, Ven. Shilabhadra has engaged in philanthropic activities that have had a positive impact, both spiritually and materially.

The next destination during my visit in Comilla was to be Ancient Shalban Vihar. I set off after paying homage to Ven. Shilabhadra, and spent quite a bit of time walking around the historic Buddhist ruins.

Ancient Shalban Vihar

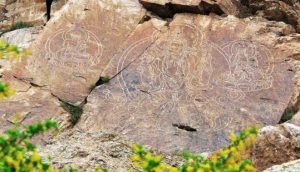

Ancient Shalban Vihar is Comilla’s principal archeological monument of interest. During archaeologist Nalini Kanta Bhattasali’s (1888–1947) tour of parts of East Bengal (present-day Bangladesh), he found several Buddhist sites, including Shalban Vihar, and reported his findings in his book Iconography of Buddhist and Brahmanical Sculptures in the Dacca Museum (1929). His book mentions about 55 scattered ancient remains of settlements from the 8th–12th centuries, known as Mainamati Lalmai, located throughout Comilla District. Shalban Vihara is in the middle of the Mainamati range and consists of 115 small rooms for monks spread across 168 square meters.

Excavations at Ancient Shalban Vihar commenced in 1955 and, so far, items such as copper plates, gold and silver coins, and more than 150 bronze statues have been found. Ancient Shalban Vihar holds the largest number of stone sculptures and terracotta plaques among Comilla’s archaeological sites. Many items were taken to Mainamati Museum, where they are now on display. The museum has perhaps the richest collecton of artifacts among all museums in Bangladesh.

Before entering the site, I read the history of Shalban Vihar in both Bengali and English on the board at the entrance. Although I knew about the site, again I read and knew that the Pala dynasty, a series of Buddhist rulers spanning the 7th–12th centuries, dominated Bengal. Under their patronage, many world-famous monasteries were built, the remains of which are revealed in the archaeological sites of Bangladesh.

When Hindu and Muslim rulers dominated Bengal, many important monasteries and stupas were destroyed. Only later were they rebuilt and replaced. As a result, what we see today are not necessarily the original Buddhist edifices, but a combination of periodic changes and architectural modifications. Ancient Shalban Vihar is one such example, as many objects from Hindu-dominated periods were also found during excavations.

Ancient Shalban Vihar is a delight to the eyes. When I came closer to the center of the site, I was astonished to see ruins of a pagoda-shaped structure. From this structure, one can easily notice that Ancient Shalban Vihar consists of six different structures built successively on the same spot during different periods and on different foundations. With exquisite decorations and beautiful structures, the heritage site can be defined as a complex of inner chambers with unique functions. Thousands of tourists from different faiths visit this heritage site to discover a core story of Bengali Buddhism.

However, I have since learned that researchers in Bangladesh are requesting the government for increased budgetary allocations in order to preserve the important cultural heritage sites of this beautiful country—and for good reason. Bangladesh is a forgotten repository of South Asian Buddhist heritage, and it is high time that its sites are given the attention and care they deserve.