When we talk about Buddhist art, one tends to think of sculptures in stone or bronze, or monumental caves and wall paintings. However, when Buddhism was introduced to China, it also found expression in the traditional Chinese art forms of calligraphy and painting. These two art forms have long been ranked the highest in the hierarchy of fine art in China, and calligraphy and paintings with Buddhist themes most tellingly illustrate the interplay between Buddhism and Chinese culture. Buddhist images and texts have inspired many Chinese artists and, in return, Chinese painting and calligraphy have opened up new avenues for the sangha to perfect their virtues and express their jingjie or spirituality.

Over the past 30 years, Fan Keqin, who is based in Shanghai, has amassed an impressive collection of Buddhist-themed Chinese paintings and calligraphy. These works, dating from the Tang dynasty (618–907) all the way to the Republic Period (1912–49), were created by some of the most influential Buddhist monks, scholar officials, and professional artists throughout Chinese history.

Fan’s collection houses works by painting masters, such as Qi Baishi, Zhang Daqian, and Li Keran, who have set auction records in recent years. However, it is not their works that he values the most. To Fan, a good painting shows the cultivation and spiritual capacity of the painter. “People are attracted to images that are pleasant to the eye, but when I see a good painting of the Buddha or a bodhisattva, my heart feels overjoyed and blessed,” Fan said to me as he brought out a hanging scroll from a delicate lacquer box that had been placed in a bigger wooden box.

The hanging scroll is an elegant ink painting by eminent monk Yishan Yining (一山一寧) (1247–1317) of bodhisattva Manjusri riding on a lion. At the age of 52, Yishan Yining was sent to Japan as an envoy by the Mongol Yuan court to restore relations between the two countries. At first, he was detained on suspicion of spying, but he soon won respect and popularity as a Chan (or Zen in Japanese) master among the ruling class. In 1313, Yishan Yining was invited by the retired Emperor Go-Uda to become the abbot of Nanzen-ji (南禅寺). Fan told me: “I acquired this painting from Japan. You see they have done a wonderful job in preserving cultural relics.”

Flicking through a catalogue of his own collection,*“Nowadays there is a lot of hype in the art market. Zhang Daqian and Qi Baishi have fetched more than 2 billion yuan [US$290 million], but are they really that good compared with these paintings?” Fan commented, pointing at a painting by Qian Huafo (錢化佛) (1884–1964). “I don’t think so.”

Qian Huafo was a legendary figure and renaissance man. In his early years, Qian was actively involved in the revolutionary movement aimed at overthrowing the Manchu Qing dynasty. During his studies in Japan, he joined the Tongmenghui led by Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925), who would later become the first president of the Republic of China. However, when Sun Yat-sen offered him a position in the newly-founded government, Qian declined and returned to his life-long passion for the arts. He co-founded the Asia Film and Theater Company and played comic roles in silent films and huaju (a type of Chinese drama featuring spoken dialogue). During his life, he collected a wide variety of objects, ranging from paintings and calligraphy to snuff bottles and matchbox pictures.

As a lay Buddhist, Qian Huafo was most renowned in his day for depicting Buddhas and bodhisattvas. In fact, he adopted the name “Huafo” later in life, meaning “transforming into the Buddha.” His paintings are characterized by their theatrical effect and lively color contrast, but his brushwork is mature and refined, and his figures solemn and dignified. While devoting himself to the arts and to Buddhism, Qian continued to work for the protection of the Chinese nation, albeit in a more peaceful way. To help laborers who were injured in anti-foreign and anti-imperialist demonstrations, he raised money by selling his own paintings and others from his collection. He also removed and kept many bulletins posted by the Japanese army in Shanghai, running the risk of being arrested and killed. After 1949, Qian submitted the bulletin collection to the Communist Party of China as historical documents.

Halfway through my visit, Fan unrolled another handscroll. Eight meters in length, the scroll gathered together 100 pieces of calligraphy by 100 prominent figures of the Republic period, all repeating the same Chinese characters—阿彌陀佛 (Amituofo), the name of Amitabha. This collective was initiated by Qian Huafo, who was very well-connected, rubbing shoulders with the founding fathers of the new China, popular actors such as Peking Opera star Mei Lanfang (1894–1961), and prominent monastics such as the Buddhist reformer Venerable Taixu (1890–1947). In Pure Land Buddhism, reciting “Amituofo” is an important method used in meditation and a means to guarantee one’s rebirth in the Pure Land. The handscroll manifests this unwavering faith in those turbulent times.

It was certainly not easy for Qian Huafo to complete this collective work, and it was also not easy for Fan to obtain it. Fan discovered this handscroll in 1988, when he had just begun collecting. The owner, a Hong Kong businessman, asked 50,000 yuan for it. “That was an astronomical figure for me,” Fan said. “The biggest note at that time was 10 yuan.” However, having thought about it for two months, Mr. Fan was deeply convinced of the significance of the handscroll and borrowed money to purchase it. He recalled, “That businessman was surprised when I showed up at his door again. He did not expect that I would be able to afford it.”

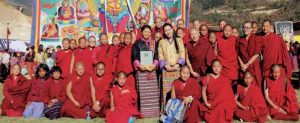

After acquiring the handscroll, Fan continued Qian Huafo’s work, adding 50 more writings of “Amituofo” by Buddhist leaders of the present time—including Ven. Benhuan (本煥) (1907–2012), Ven. Delin (德林) (1915–2015), and Ven. Mingxue (明學)—to the scroll. The title on the frontispiece of the handscroll was inscribed by Zhao Puchu (趙樸初) (1907–2000). Fan plans to continue this project and collect more writings. A few years ago, the former owner asked whether he could buy the handscroll back for 500,000 yuan, but Fan declined.

Collecting is Fan’s profession by choice; when he graduated from middle school in 1976, he had limited options. By government assignment, he was supposed to become a cook or a shopkeeper, which did not interest him in the slightest. Instead, Fan obtained a high school degree by taking evening classes and studied the mounting of Chinese paintings and calligraphy. His mounting skills landed him a job at the Shanghai Institute of Culture and History and subsequently at the Jade Buddha Monastery, where he helped to manage the art collections. It was during his time at the Jade Buddha Monastery that Fan converted to Buddhism.

Fan’s pursuit combines his expertise and spiritual interests; “I believe in karma—good results in good and bad results in bad—it is not superstition. Buddhism has guided me in conduct.” Discussing the soaring prices of Buddhist art today, Fan observed: “When I started collecting Buddhist paintings and calligraphy, people did not see the point of it. Now, thanks to the resurgence of Buddhism, people think I was farsighted and that I am doing something meaningful. In this sense, I am really lucky.”

The collection continues to grow, as Fan travels around the world, each year, looking for Chinese paintings and calligraphy to add to his collection. He has exhibited his collection at major Buddhist monasteries in southern China and has donated works by eminent monks to monasteries where they used to stay or that they used to manage.

* See Fan Keqin, bimo puti – fojiao shuhua cangzhen, Shanghai, 2009 (樊克勤,《筆墨菩提 —— 佛教書畫藏珍》,上海,2009).