Whilst many museums around the world have historically collected works of art from Myanmar, few have mounted exhibitions dedicated to the Buddhist art of that country. The pioneering show Buddhist Art of Myanmar, on view at Asia Society Museum in New York until 10 May this year, brings together major works from national museums in Myanmar and pieces from American collections. Intriguing, rarely seen or published works are now well documented in the accompanying catalogue by curators Sylvia Fraser-Lu, Donald M. Stadtner, and Adriana Proser. Ambitious in scope, this carefully chosen exhibition speaks to the expert as well as audiences keen to learn more about Buddhism in Myanmar and the significance of its many forms of artistic expression.

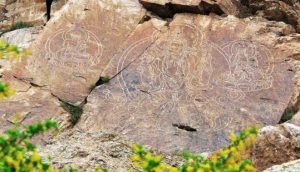

The religious tradition goes back to the early centuries of the Common Era, although the earliest records are stone inscriptions of the 11th or 12th century from Pagan. They refer to a myth of the Buddha’s prophecy that the ancient Pyu city of Sri Ksetra would be founded by “Bisnu” and that 1,630 years later, he would be reborn as King Kyanzittha (c. 1084–1112). Other myths also speak of the Buddha visiting the country during his lifetime. The earliest work in the show is a very large stone stele from around the 4th to 6th century which was excavated northwest of the palace of Sri Ksetra (Fig. 1). This impressive object sits on open display at the entrance to the exhibition. New York audiences first saw this piece at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Lost Kingdoms exhibition last year. On one side, protective deities wielding weapons may represent the earliest images of local gods, but who or what are they protecting? Scholars seem equally if not more intrigued by the image of a throne carved on the reverse. This is an unusual non-representational (or aniconic) image of the Buddha, associated with his teaching. In Southeast Asia, symbols of the Buddha more typically include the “Wheel of Law” (dharmachakra), the two deer associated with the first teaching at Sarnath, and footprints. The joy of discovery is palpable as visitors spend time examining the qualities of the sandstone up close and then stand back to take in the worn reliefs of the figures. The stele is raised almost to eye level with a new mount and is further illuminated by raked spotlights—display mechanisms that are easy to take for granted but which many museums in Southeast Asia do not enjoy the privilege of having.

Once inside the exhibition, there is a strong thematic thread—the Image of Buddha, the Life of Buddha, his Birth Stories or Jataka, and Ritual and Devotion, including the related tradition of Nat Worship. Images of the Buddha, in wood, sandstone, alabaster, bronze, and silver, took many forms over a period of about 1,500 years. The distinctive sandstone figures of central Myanmar are poignant evidence of the artistic innovations associated with the flourishing Bamar culture at Pagan (11th–13th century). This large seated image with hands in dharmachakra mudra (the “Wheel of Law” or teaching gesture) has typical attributes—a solidly carved body with delicate hands and facial features, so beloved by Pagan artists (Fig. 2). This image has gained something of a reputation through its association with a local shrine that houses a replica, and pilgrims now include a visit to the Bagan Archaeological Museum to pay their respects. Its importance was illustrated when rituals were held before the piece was packed and shipped to New York earlier this year. Another more dynamic image depicts the Buddha’s renunciation, in which he cuts his hair with a huge sword (Fig. 3). What we see now may well have looked very different in earlier times. For example, traces of pigments on the backslab and areas of the body of the second piece suggest that these works were once extensively painted.

There are several interesting small works made with precious materials, one of which has never been displayed before. This standing figure of the Buddha with the right hand lowered in varada mudra (the gift-bestowing gesture) and the other holding the end of the robe is rare for this early period (c. 8th–9th century) (Fig. 4). The quartz has appealing striations that become more apparent when the piece is held up to light. According to Don Stadtner, quartz was more often used at this time for relic containers—clear quartz enabled the relics within to be viewed.

A small gallery explores the Birth Stories or Jataka, which relate to the Buddha’s previous lives. In Myanmar, as in other parts of Southeast Asia, the story of the generous prince Wethandaya (Vessantara) is frequently encountered. Scenes of the most poignant moment—the giving-away of his children to the old Brahmin Jujaka—are depicted time and again in many media. This and other Jataka stories are illustrated here with just three objects—a silver betel box, a lacquer food cover, and a wall hanging known as a kalaga, a type of elaborate embroidery that became popular during the colonial period (late 19th–early 20th century). Here, Jujaka is seen mistreating the children, and when they are left at the foot of the tree where he sleeps, deities arrive to protect them (Fig. 5).

The last gallery explores a broader notion of Buddhist art through the themes of Ritual and Devotion. The meritorious value of creating and donating sumptuous objects becomes evident through an inscription on a bronze bell, dated 1884, that records its donors’ intentions—a mother and daughter from Pyin-bya Village in Thing-gon District made this gift “. . . with a clear, detached mind full of good intentions with a desire for their beloved family and friends to follow the precepts, escape the cycle of life, pay homage to Metteyya the future Buddha, and to ascend to the blissful state of nibbana.” A striking contrast to the earlier galleries, this one is dominated by colorful ritual objects including lacquer offering vessels inlaid with glass and semi-precious stones, painted manuscripts, and carved architectural embellishments of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Figures like the striking pair of bird-human keinaya, decorated with inlaid glass and gilded lacquer, represent the heavenly realms, and are often present as auspicious architectural adornments on pagoda platforms (Fig. 6).

The lasting impression a visitor leaves with is the richness of the Theravada tradition in Myanmar. The historical incorporation of Hindu deities is present in the form of two small figures of Vishnu and Brahma, images of which can still be found at pagodas today. Mahayana elements can also be found—this figure of Lokanatha is a form of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion and guardian of Buddhism until the arrival of the future Buddha Metteya, and is depicted here in royal costume with Indian-style jewelry (Fig. 7). There is also the mythical nature spirit or nat tradition, present here in the form of a tiny figure in the center of the base of a bronze image of the Buddha and his two disciples (Fig. 8). According to Sylvia Fraser-Lu, this is the guardian spirit of trees and forests, also known as Youkkhazou. Depicted wringing out his two braids of hair, he is said to have guarded the Bodhi Tree under which the Buddha sat when he achieved enlightenment (Fig. 8). Nat worship is very much alive today, but this piece, dated by inscription to 1628, reminds us of the unique coexistence and enriching contribution made by local beliefs to the Buddhist arts of Myanmar.

For more information on the exhibition and catalogue, visit Buddhist Art of Myanmar.

References

Fraser-Lu, Sylvia, and Donald M. Stadtner, eds. 2015. Buddhist Art of Myanmar. New Haven and London: Asia Society Museum in association with Yale University Press.

Heidi Tan was principal curator for Southeast Asia at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. She is an Alphawood Foundation scholar currently pursuing a PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.