In some countries in Asia Buddhism still takes the form that it has assumed for well over a thousand years. Due to its long-standing tradition, many people believe that as a religion it has always been relatively popular, gone unchallenged, and remained immune to external oppression, and that today it is spreading effectively throughout the world. However, two recent talks by Professor Lewis Lancaster, “Contemporary Buddhism: Peak of Revival” and “Tomorrow’s Buddhism: Moving Time and Place,” which took place at The University of Hong Kong on 1 and 15 November, offered a fresh perspective on the survival and state of Buddhism over the centuries.

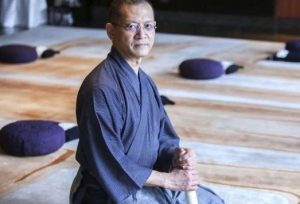

Lewis Lancaster is professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. His research relates to different aspects of culture, and he is highly active in the international arena, working with Buddhist educational institutions in the USA, Taiwan, Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, and Malaysia. His current work includes the development of installations of 3D and virtual reality projects as part of a long-standing interest in the use of digital technology for Buddhist texts. He is also editing the Atlas of Maritime Buddhism in collaboration with the Maritime Museum of Hong Kong, which “aims to examine the way in which mercantile activities from the early centuries of the Common Era were inspired by religious agendas as well as profit,” while focusing on Buddhist archeological sites.

In his first talk, Professor Lancaster reflected on how the advent of European colonialism in Asia, and the associated influx of Christian missionaries, challenged the Buddhist hegemony in many countries. At that time, the Portuguese Popes were also appealing to the colonialists to establish Christian missions in Asia. This was the first threat to Buddhism in Asia, and led to many Buddhists converting to Christianity. The second came with the spread of Marxism across Asia, causing Buddhism to collapse in China, Russia, Mongolia, and Tibet. Many Buddhist monasteries were given over to industry, and Buddhist scriptures were burned. From 1920–40, around 100,000 monks were expelled from monasteries in Mongolia alone.

Although these were difficult times in the history of Buddhism, many people continued to maintain Buddhist precepts and practices. Decolonization and the relaxation of communist rule marked the revival of Buddhism in China, eastern Russia, Taiwan, Vietnam, and elsewhere. Since 1975, Buddhism has again begun to thrive, with thousands of monasteries being built and many monks being trained to teach. In China, at the beginning of the Buddhist renaissance, five novices trained under a single monk. This period has come to be called the “peak of revival” in contemporary Buddhism. Nonetheless, there are still signs of potential decline in many countries. For example, the speaker highlighted the problem of falling demographic rates in Japan and China—in China, since the one-child policy was adopted in the 1980s, the Buddhist population has fallen significantly. In Japan and Korea, both considered Buddhist countries, the allure of city life is a centripetal force drawing the younger generations from villages to urban areas. The inevitable result is that Buddhism has not caught up with the cosmopolitan spirit of city life and has remained a religion mostly practiced by elderly people in the countryside. Moreover, in Taiwan, although the number of monasteries has increased from 3,400 in 1983 to 15,000, the number of monks with a real capacity to act as spiritual leaders for the general populace is very low, even among those currently in office.

At the end of the talk, the speaker concluded that, due to European colonial domination, Marxist oppression, and the ideology of the younger generation, Buddhism has in fact often fallen out of favor. And although Buddhism is no longer oppressed by missionary activities and Marxist forces, due to falling demographics in China, Japan, and Korea, the general trend of declining Buddhist populations is inevitable in these traditionally Buddhist countries.

Professor Lancaster began his second talk on a cautious note of optimism for the future of Buddhism in Asia. He explained that in Taiwan, for example, many monasteries are in fact underpopulated or closed. Due to concern for the future of Buddhism in Taiwan, many Vietnamese monks are being trained in Buddhist colleges in Vietnam and will move to Taiwan to assume a leadership role in its monasteries after completing their studies. However, the professor did not address the reason for the falling interest in Buddhism in Asia in general and how the tendency could be reversed. His discussion then moved to the West and the rising interest and participation in mindfulness meditation practice, which he suggested was the form Buddhism would most likely take in the future. He especially highlighted the influence, since the late 1970s, of neurologists like Jon Kabat-Zinn, professor of medicine emeritus and founder of the Stress Reduction Clinic and the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, who has made great contributions to the promotion of Buddhist meditation in the mainstream of science and medicine.

Stressing the importance of mindfulness meditation, Professor Lancaster asserted that one of the most scientific and convincingly evidence-based uses of mindfulness is in clinical applications. Today, thousands of neurologists are eager to promote the practice in the West in order to reduce stress. Mindfulness practice also helps improve students’ attitudes to life and the ability to concentrate in class. He gave as an example the documentary Room to Breathe, which is a surprising story of the transformation of struggling children in a San Francisco public middle school when they are introduced to mindfulness meditation. In this regard, he also discussed how the practice is being adopted at Tonbridge School in England and at George Mason University in the United States.

Many organizations are now also teaching mindfulness-based meditation programs in prisons in both the East and West, as a secular tool to help practitioners shift from blind reaction to skillful response. The speaker made reference to the application of the Burmese-Indian spiritual master S. N. Goenka’s technique of mindfulness practice in jails, as in the documentary Doing Time, Doing Vipassana. He also gave the example of Kiran Bedi, inspector general of Tihar Jail in New Delhi, who introduced Goenka’s ten-day course to the prisoners as well as police in 1994. The professor further mentioned Chade-Meng Tan, Google’s software engineer, who is actively promoting a mindfulness culture in transnational corporations. Tan’s book Search Inside Yourself is now becoming a popular read.

Professor Lancaster ended his second talk with the wish that tomorrow’s Buddhism will not only be practiced by traditional Buddhists, but that it will transcend the boundaries of religion, race, caste, and culture. Exploring the science of mindfulness and its power, he concluded that Buddhism has a great deal to offer the West, and that mindfulness meditation will be taught and practiced more widely in schools, hospitals, doctor’s offices, military camps, and many other vital institutions.

Professor Lancaster’s talks offer a fairly realistic assessment of the actual situation of Buddhism in the 21st century: although it faces numerous challenges, there is still hope that tomorrow’s Buddhism will not be limited to a small group of traditional Buddhists, but that it will also find acceptance among a more cosmopolitan audience.