Tsum Valley, in Nepal’s western Gorkha District, is one of the Himalayan country’s lesser known jewels. It was officially opened to foreign tourists in 2008 as part of a government effort to promote sustainable tourism, bolster economic development, and highlight the unique cultural and natural treasures of the Manaslu Conservation Area, established in 1998.

It lies a world away from the ceaseless clamor and the dusty thoroughfares of Kathmandu, yet the inevitable ingresses of modern tourism mean that Tsum Valley is no longer the hidden secret it was even as recently as 15 years ago. Yet the valley is still far enough from the beaten path that its resplendent landscapes and secluded communities retain the mystique of a rich and ancient way of life in Nepal’s geopolitically sensitive border region with Tibet.

The Buddhist traditions of the Himalayas are deeply embedded in Tsum Valley, as evidenced by the unique and historic Buddhist temples, monasteries, and other landmarks that punctuate the rugged landscape. Among them: Rachen Gompa and Mu Gompa, which stand on a scenic plateau in the lap of the valley, Gompa Lungdang, at the foot of a conical hill, and a revered cave where the Buddhist saint Milarepa himself is believed to have meditated.

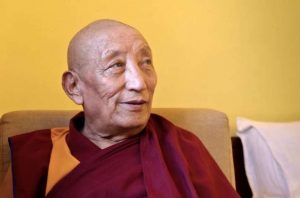

One of the children of Tsum Valley is Khenpo Karma Samdup who, despite humble beginnings in one of the valley’s most remote villages, would go on to become a close student of revered tulku of the Karma Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism, Yongdzin Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche (1933–2023). Khenpo Samdup is now the general secretary in charge of Thrangu Tashi Choling Monastery, which Thrangu Rinpoche established in the Buddhist enclave of Boudha in 1979.

BDG was privileged to sit down for an informal conversation with Khenpo Samdup to learn about his life in Tsum Valley and his Dharmic connection with one of the most senior lamas in the Kagyu school of Vajrayana Buddhism and one of the most highly respected Dharma masters of modern times.

BDG: Thank you for sharing your time with us this morning, Khenpo Samdup. Could you tell us a little of your family history?

Khenpo Karma Samdup: My family is from Tsum Valley in Nepal, on the border with Tibet. Although our ancestors are originally from Tibet, we have lived in Nepal for several generations and so we now consider ourselves Nepalese—of course, in the old days, unlike today, it was much easier to come and go across the border with Tibet for commerce and travel.

I grew up in Tsum Valley, where I had a happy childhood. Traditionally in our culture, when a family has a daughter she should help her mother with domestic chores—cleaning, carrying water, making the fire, preparing tea, cooking, and so on. Our family had five sons and one daughter. As the middle child, I was always very active helping my mother around the home and so everybody liked me!

Even when I was very small, I become known for my insistence on telling the truth. For instance, if I broke a cup and somebody asked me what happened, I wouldn’t lie to escape blame; I would admit that it was my fault and accept my punishment willingly. While some children in the village would often lie about such things, it wasn’t something I could easily accept. My nature was like that, even from a young age.

Now I’m here at Thrangu Tashi Choling Monastery as the general secretary. Since 2017, I’ve been teaching higher Buddhist philosophy at the monastery. On 1 December 2022, I and was awarded a master’s degree in Higher Buddhist Studies by Ven. Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche and received the title “khenpo.”

BDG: What circumstances brought you from Tsum Valley to Thrangu Monastery?

KKS: I first came to Kathmandu when I was 12 years old. My close cousin brought me here to the monastery, with the permission of my parents, of course. In those days, it took us nine days to reach Kathmandu from my village in Tsum.

At that time, our village had no English school or Nepalese school, we only had the teachings of Buddhism passed down through the generations, and some of us would learn how to read and write Tibetan—or try to. In fact, many people couldn’t read or write, and we didn’t know how to properly conduct pujas. But we liked it very much when real pujas were organized; we loved to travel to join in whenever a Buddhist ceremony was being conducted—to see: How do they pray? How do they prostrate? How do they make offerings? How do they play the Dharma instruments? We liked this very much! This was our true culture. But because we lived in a very remote area and we didn’t have any schools, it was difficult to receive a formal education in these matters. And even if we did want to travel to take part in such events, it was very difficult as we really didn’t have any money to spend.

Perhaps my karma and my luck at that time were very open? I became the second person from our village to become a monk. The first was my cousin, Khenpo Dawa—he’s now based in Hong Kong. It was he who brought me to Kathmandu, and thus I became the second monk from our village.

BDG: That must have been a great change for someone so young?

KKS: At that time in Kathmandu, this area was all fields; everything was green, no houses—or very few. Nowadays, it’s become very built-up. Thanks to my background and life in Tsum Valley, I was very keen to become a monk and to study Buddhist philosophy, but there were few opportunities in Tsum.

Then my cousin came to visit our village, and he asked me: “Do you want to come back with me to Kathmandu?” I quickly agreed, and so he asked my parents for their permission, and they consented willingly. To be honest, my mother was a little reluctant, saying, “If you go, I’ll no longer have my little helper!” But my cousin assured them that in the future I would make them proud, and so they gave their approval.

So I came here to Thrangu Monastery when I was 12 years old and attended the monastic school here. After about three years, I became an assistant to one of the old khenpos until I felt ready to continue my studies. I received permission from Thrangu Rinpoche to study Buddhist philosophy—first in Nepal at Thrangu Tashi Yangtse Moastery in Namo Buddha, and later, in 1999, we went to the Vajra Vidya Institute that Rinpoche established in Varanasi, India.

After I completed my studies in Buddhist philosophy, Rinpoche instructed me to stay on and manage the institute in Varanasi, which I did for two years. Then, in 2004, I returned to Nepal to teach young monks at Thrangu Tashi Yangtse Monastery until 2011.

It was around this time that my father became sick. It was very difficult to get medical treatment in Tsum Valley at that time. My father wanted to retreat to a high cave in the mountains to practice before he died. Although his condition was worsening, he didn’t want to go to a hospital in Kathmandu because it was prohibitively expensive. He didn’t want to create a big problem for the family. Because he was a practitioner, he went to meditate in a cave high in the hills, where nobody would see whether he was alive or dead.

When my aunt went to visit him, she saw that his condition was deteriorating. They sent word to me in Kathmandu, just as I was about to travel to India again. When I received the news, I canceled my ticket and tried to bring my father to the city. However, because I didn’t have enough money at that time, I had to borrow 80,000 rupees to bring him to the city by helicopter. We took him to a hospital, where they told us he was suffering from late-stage cancer and that there was nothing they could do. He stayed at the hospital for another nine days before he died. After that, I made sure to arrange all the traditional Buddhist funeral ceremonies and pujas for my father over 49 days.

After everything was concluded, I remembered my father’s wish that I should undertake a formal retreat—to practice. It’s not enough to study Buddhist philosophy, he had told me; you also need to practice.

Before this I had been unable obtain permission from Rinpoche—I didn’t want make a formal request because Rinpoche had given me many responsibilities: looking after monasteries; taking care of the schools and the young monks; teaching, taking care of healthcare matters; so many things I had to do. If I had sent a request to Rinpoche to go to the retreat center, I would have felt like I was trying to escape my responsibilities and not following Rinpoche’s instructions. That was how I felt.

Then, with my father’s passing, I realized finally that it was time. I had to go. So I wrote my formal application to Rinpoche, seven pages long. However, he didn’t give his permission immediately, he simply replied, “Let’s see.” So I wasn’t feeling very good at that time.

BDG: There must have been a good deal of pressure from your monastic responsibilities and your family circumstances?

KKS: Coupled with some ongoing issues between some of the monasteries at that time, my heart was no longer in my work. Speaking bluntly, if Rinpoche hadn’t finally given me permission to undertake a retreat then perhaps I wouldn’t be working at Thrangu Monastery today.

But Rinpoche finally relented. He wrote a letter instructing me to return to Namo Buddha to teach and to look after the young monks. “After one year,” he said, “then you can go.” Now I had my chance, I was able to undertake a formal retreat of four years and four months.

When I eventually returned from my retreat, Rinpoche appointed me to return to Namo Buddha as the head monk, then in 2017 he brought me back here to manage the administration office at Thrangu Tashi Choling Monastery in Boudha.

BDG: When did you meet Thrangu Rinpoche for the first time?

KKS: I first met Rinpoche in 1989. I met him face-to-face when I was 12 years old. When I first arrived, Rinpoche was traveling outside of Nepal, so I helped in the kitchens for two months, peeling potatoes, carrying oranges, sweeping the floor, and so on. When Rinpoche returned, my cousin brought me to him to request his permission for me to become a monk. Rinpoche assented, and I was sent to be educated.

Q. How did your relationship with Rinpoche develop?

KKS: I was very fortunate. Rinpoche believed in me. Thrangu Rinpoche was very very compassionate toward the monks—all of the monks. Even when he was traveling in Europe or North America, Rinpoche would call and ask about the welfare of the monks in Nepal, to make sure that everyone was healthy and that the food was good, and to find out what was going on while he was away. He was always very compassionate in this way.

I feel extremely gratified that Rinpoche always believed in me and my work for the monastery. Wherever he appointed me, he trusted me to work well. Sometimes Rinpoche would even call me to his room to advise him on various matters related to life at the monastery. It was a great honor that he trusted me on such important issues; you know, Rinpoche is Rinpoche! He was the head of our monastery, of all the monasteries. We are all under Rinpoche, yet Rinpoche was seeking my counsel on what we needed to do—how we should develop the monastery or improve healthcare, and so on.

Of course, Rinpoche was also very precious to me in terms of our Dharma practice. He was not only a profoundly knowledgeable Buddhist scholar, he was also a deeply accomplished meditation master. So it’s a great privilege for me that I could be connected with him; it’s a great source of joy.

Although Rinpoche has passed away, we don’t have any regrets: whatever Rinpoche worked for in his life, he did very well. We all learned so much from him that’s there’s nothing to feel regret about now. While we are waiting for his reincarnation to be identified, we have to look after the monasteries, we have to try our best as we continue with our work, just as we did when Rinpoche was alive.

In this world, nobody can stay here forever; one day we all have to die. This is the reality of impermanence. If Rinpoche were still alive, we would be very happy; yet although he is no longer with us, we don’t have any regrets because of what Rinpoche showed us and taught us about the Buddhadharma and our practice, and even how to be a good human being. This is what I most appreciate about Rinpoche.

The rest is out of our hands. If you can do good things, develop in your practice, develop yourself into a good human being, that’s in your hands, and that is what’s most important, even if you do nothing else. Rinpoche showed us and gave us and taught us these precious things.

BDG: Do you have any personal aspirations for your work now?

KKS: Actually, in Buddhism, what I’ve learned in my life, what I have come to understand about what I have to do, the main point is to work for the benefit of the Buddhadharma and for the benefit of all sentient beings. The main point is wherever we are needed, we have to help. Where is there no education? Where is there no Buddhadharma? Where are there no monks or lamas? Where are people very faithful to the Dharma but there are no teachers or monasteries or retreat centers? That’s where we’re needed. If we can help people in these situations, it will be of great benefit and people will be very happy. So this is where I want to focus my attention in this life.

You have visited Tsum Valley and seen life there. Some of the villages nowadays have very good amenities and facilities. But there are also some very poor villages still, where they’ve never seen motor vehicles. People who only have one set of clothes to wear, and who rarely have opportunities to properly practice the Dharma. So I would like the opportunity to find a way to really benefit people living in these circumstances.

BDG: Thank you so much for sharing your wisdom and experiences with us, Khenpo Samdup.

See more

The Very Venerable Ninth Kenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

Thrangu Tashi Yangtse Monastery

Related features from BDG

Buddhism in the Hidden Valley, Part 1: An Ancient Heritage in Tsum

Buddhism in the Hidden Valley, Part 2: Heritage Conservation in Tsum

Buddhism in the Hidden Valley, Part 4: Conservation and Community at Rachen Gompa

Buddhism in the Hidden Valley, Part 5: In Conversation with Rachen Gompa’s Geshe Tenzin Nyima

Related news reports from BDG

The Revered Buddhist Scholar and Tulku Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche Has Died

Last Rites for Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche Begin at Thrangu Tashi Yangtse Monastery