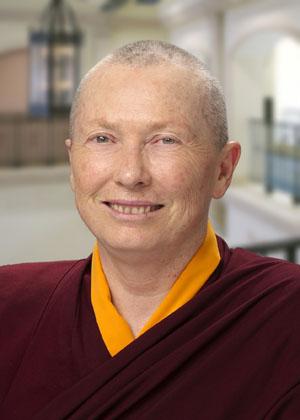

Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo is the Branch and Chapter Coordinator of Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women. In this series of seven questions we presented to her, she reflects on some key issues about Buddhist women and the long road ahead.

B: How involved are traditional Buddhist organizations and foundations with Sakyadhita? In general, do they recognize women’s critical role in the future Buddhism, or do most still seem to resist any calls for change or reform?

KLT: Most Buddhists seem to totally ignore women’s issues and women’s roles. Most traditional organizations are not involved at all. Most Buddhists seem unaware of the critical role women can play and do not seem to care about women’s disadvantaged status. Buddhists seem to believe their own propaganda that women and men are equal in Buddhism, and are blinded to the blatant inequalities that currently exist. Some Buddhists pay lip service to women’s importance, but institutional structures do not reflect any commitment to women’s advancement or to women’s equal participation. In fact, the mantra that women and men are equal in Buddhism acts as a kind of smokescreen to mask inequities that are clearly visible. Women continue to be sidelined in public forums, even by educated and otherwise compassionate people, both women and men.

When traditional institutions acknowledge the importance of women at all, they often do this by consigning women to traditional roles within archaic structures and praising women for staying in those roles. If they enlarge women’s roles, for example, by allowing women to teach or to occupy an administrative role, they do so without really reforming the organizational structures and ethos of their organizations to give women autonomy, independence, and leadership opportunities.

In response to a growing awareness of the need for more equal representation of women in Buddhism, women, especially female monastics, may be pressured to step into teaching and leadership roles before they are fully grounded and trained. Instead of nurturing women’s leadership or giving nuns the chance to get solid training and education, they may be thrust into positions of authority and pressured to teach and provide leadership without the preparation that their more privileged brothers get. Occasionally, in an effort to be politically correct, a woman may be thrust into a public role, ignoring the fact that leadership requires preparation, education, and experience. “Buddhism at the Grassroots” means preparing women from the ground up, by providing the causes and conditions for successful leadership: systematic education, health care, training, and experience, so that women will be fully qualified to take leadership roles. Buddhists urgently need qualified people to represent Buddhism in public discourse and it is impossible to speak with authority unless one has adequate preparation and encouragement. All of this requires resources that Buddhist women in most countries do not have. So, we are stuck in a bit of a Catch 22. We need support to nurture Buddhist women leaders and we need Buddhist women leaders to help garner this support. The most crucial phase is when women are first starting out and struggling; once they are published and internationally acclaimed, support comes naturally.