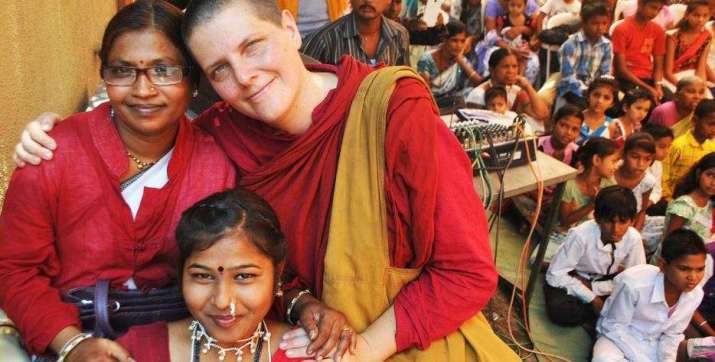

“Happiness is not just a personal matter; it’s a communal matter,” says Venerable Yeshe Chodron, known as Ayya Yeshe, in an online introduction to her foundation. Ayya Yeshe has taken the idea of communal happiness and made it a calling; she is the founder of the Bodhicitta Foundation, a non-governmental organization dedicated to serving the poor in India. Author of Everyday Enlightenment: How to be a Spiritual Warrior at the Kitchen Sink (HarperCollins 2006), she found Buddhism at the age of 17 after struggling with depression. Six years later, she ordained and worked at a Buddhist center in her home country of Australia, before moving to India. When she encountered poor people from the Dalit community, sometimes known as the “untouchable” caste, she was impressed by their drive for justice and human rights—and wanted to help. The Bodhicitta Foundation provides meals, education, healthcare, and counseling services to poor communities, as well as meditation and spiritual guidance.

Buddhistdoor Global: You founded the Bodhicitta Foundation to serve members of the Indian community, especially those of lower caste. Can you talk a little bit about what inspired you and how it got started?

Ayya Yeshe: When I ordained [in 2001], I had nowhere to stay; my [Australian] center charged me rent, but allowed ethnically Tibetan male monks to stay for free. In the midst of that I had many requests to teach the Dharma in schools, prisons, and rehab centers. In Australia I could not financially survive and so I went to India to study, but I missed social engagement. I went to Bodh Gaya, where there is a huge gap between the air-conditioned marble enclaves of foreign Buddhists and the poverty stricken lives of local people. Most centers had high barbed wire fences out front and I found myself wondering which side of the fence the Buddha would be on.

I then met a man from the Ambedkarite community [Dalit Buddhism, a socially engaged Buddhist movement in India] and went to Nagpur. I was inspired by the Dalits’ struggle for human rights.

BDG: Working with women and girls is a primary part of the NGO’s mission. Why is the focus on women and girls important?

AY: All the data we have on social justice shows that women and girls are the most vulnerable and face the most oppression. Seventy-five per cent of trafficked people are female. Most of the victims of malnutrition, poverty, illiteracy, and domestic violence are women. Women do 60 per cent of the world’s work, but own 10 per cent of its land. There are millions of young girls waiting for a chance to attend school. Addressing poverty and the environment, as well as population growth can all be addressed in a big way by educating female children.

BDG: You teach meditation classes and talk about the importance of giving people a place to recover from the stresses of poverty. How does the Bodhicitta Foundation help offer respite and renewal for those under chronic stresses?

AY: People who live in slums live 5–7 people in a room. Having some space from the constant struggle for survival and the violence and alcoholism, or in the case of women, the unpaid domestic drudgery, helps them uncover their own inner goodness and potential and gives them access to more inner resources and resilience. It increases well-being, saving relationships and families a lot of suffering. They now have better skills to resolve conflict and treat each other better because they have touched peace.

BDG: In your blog, you wrote, “To me this is the vocation of monastics—to be the foster parent or best friend and counselor to the whole community, not just to one family or partner or child.” Can you tell me how you see your vocation as a monastic?

AY: Dr. [B. R.] Ambedkar, who was the Martin Luther King Jr. of the Dalit community, saw monastics as social workers. People like to share their problems with monastics. We don’t have families and are not tied up in wealth generation, so we have more freedom to be beacons of sanity in a troubled world. This comes through both the spaces of refuge and peace we create in monasteries as well as hands-on social work to respond directly to the suffering world.

Everything is made of non-self elements. I can’t exist without air, water, farmers, food, my parents, the Earth and the Sun. To be spiritual is to take care of the sacred mystery of interbeing and develop empathy for all beings, our past life mothers.

BDG: What is the organization of the Bodhicitta Foundation like? How do the staff work together to help the community?

AY: We have 17 staff, mostly comprised of slum people, some of whom have made great efforts to empower themselves with education.

We have 30 girls who are studying in high school and university in our girls home. They would otherwise be working in piecemeal jobs or have been forced into child marriage because of poverty.

We make 6,000 meals per year for undernourished children. We have around 100 poor children in after school study groups, because the quality of free schooling is often bad. We also train women and adolescents in beauty therapy, computers, English, and sewing. We sponsor 55 children for school.

BDG: You hope to expand the center and create a more permanent living space. What are your hopes for this new space and what do you still need to make it a reality?

AY: Of the 15 people I was ordained with, only myself and another nun are left. Seventy-five per cent of Western Tibetan Buddhist nuns disrobe as there is really almost zero support. Although these centers may do very good work, the top-heavy structures exclude women from roles as spiritual leaders and an equal share in resources. I would like to end the patriarchy and ethnocentrism in Tibetan Buddhism. I would also like to create a place for activists to rest and people who are interested in deepening their practice and creating more sustainable livelihoods to come.